As the 90th anniversary of the Chinese military’s founding (August 1) approaches, China’s state-controlled news outlets have been publicizing the presence of the People Liberation Army’s female recruits with a series of videos and reports that highlight their skills in dancing, taking phone calls and wearing make-up.

Across the world, women in the military have historically performed support roles ranging from cooking to nursing to communications. But in recent decades they have increasingly moved into combat roles. In the case of China, the PLA trained its first 16 female fighter jet pilots in 2009, to give just one example. (One of them, Yu Xu, died in a flying accident last year.)

But the military is still heavily focused on, for lack of a better word, what it sees as women’s soft power—the same year it got its first women fighter pilots, the Chinese army also instituted a talent segment for female recruitment. And Chinese state media are following suit.

In June, China’s top state newspaper, the People’s Daily, showed off female soldiers’ dance moves in a video posted on YouTube:

On the People’s Daily Twitter account, many expressed bemusement at the dance video, which didn’t specify which units these women come from. The PLA also runs a theatrical troupe which sings, dances and performs propaganda-infused Broadway-style musicals at big events. China’s first lady, Peng Liyuan, was the head of the troupe at one point.

This month, military newspaper the PLA Daily profiled an all-women military group that transfers phone calls between China’s top leaders. Founded in 1960, the “Channel No.1” unit is based in a small compound out of Western Beijing, according to the PLA article published on July 19 (link in Chinese). The center is staffed 24/7, as female operators direct communication flows on military affairs and relief work after natural disasters. A slogan on the wall reminds all the soldiers of their duties: “Accuracy, speed, passion, confidentiality.” The article didn’t say why only women are assigned to this group.

To ensure speed, female operators must memorize more than 3,000 phone numbers, understand all Chinese dialects, and know who is calling simply by their voices, according to a separate piece published July 19 by the Legal Evening Post (link in Chinese), which rounded up previous state media reports on Channel No.1.

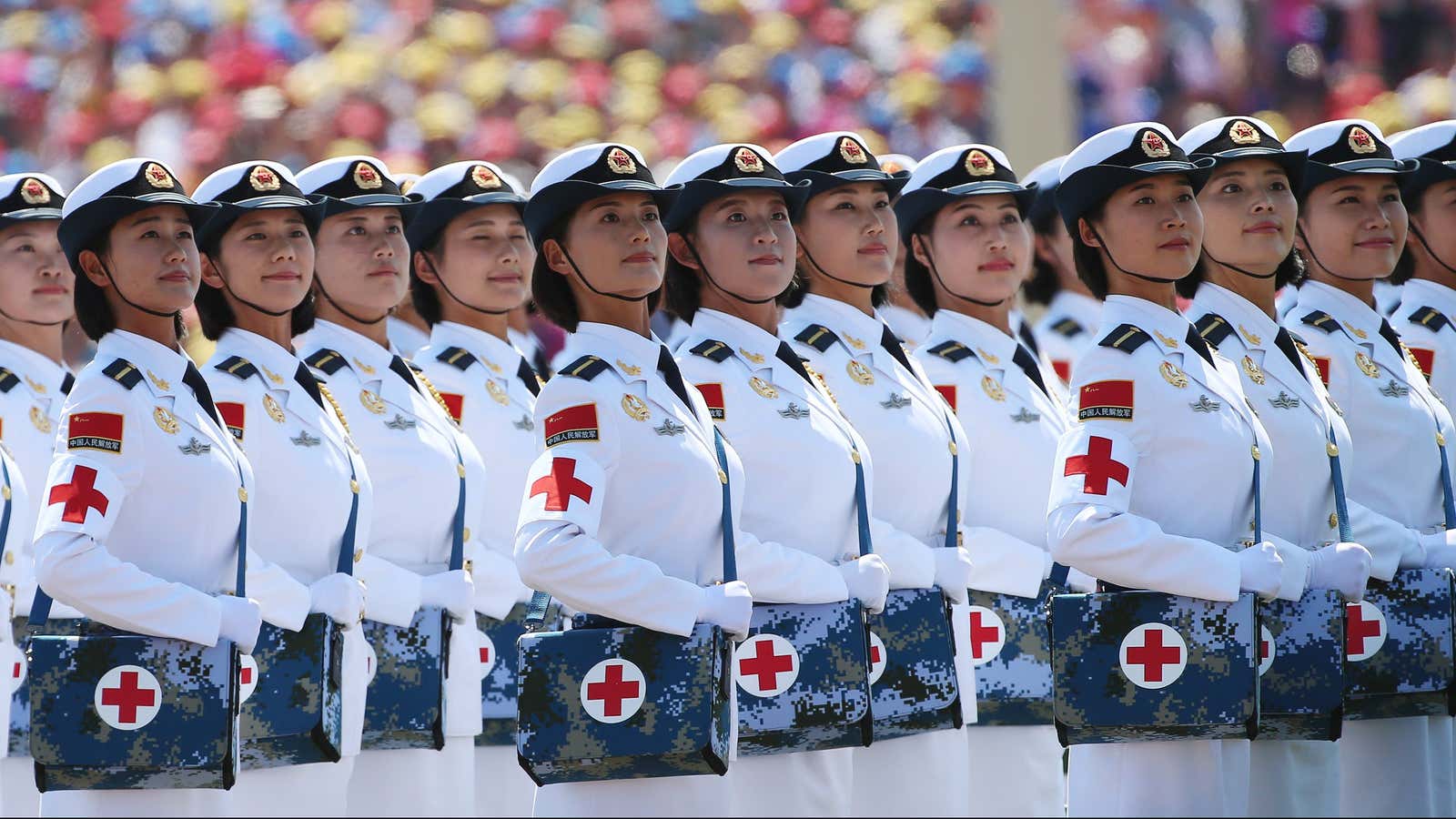

Last week, China’s top cyberspace watchdog also took journalists from over 60 online Chinese publications to visit the base of the PLA honor guards (link in Chinese) in Beijing, which resulted in a series of very similar reports focusing on the appearance of the PLA’s recently created unit of female honor guards. Honor guards have a ceremonial role, appearing in military parades.

The length, width, and height of female honor guards’ hair buns must be made 13cm (5.1 inch), 6cm, and 6cm, respectively, reported Chinanews.com (link in Chinese), quoting a 20-year-old female solider called Mao Wen. Because some of her colleagues don’t grow enough hair, Mao said, they have to make their hair fluffy to meet the standard.

“This group of good-looking Chinese female soldiers have astonished us again!” wrote 81.cn (link in Chinese), a website run by the PLA Daily, in the headline of an article about the female honor guards. The piece noted that the group was founded in 2014, and has since showed up in a series of major events including China’s World War II parade in 2015, and a recent gala marking the 20th anniversary of Hong Kong’s handover from Britain to China. All 159 female honor guards receive training in wearing light make-up, as they are required to wear it while attending events. “Learning how to wear make-up is their first lesson,” it wrote.

The depictions of the PLA soldiers are symptomatic of broader gender inequality in China, where some women have made great strides and run top companies, while at the same time few women are in top leadership roles in the Communist Party, and restrictive gender roles are common in broader society. Women who reach the ripe age of 27 without marrying are commonly mocked as “leftover women.” Increasing government efforts to prevent protest have at times focused on feminist activists. The official celebrations in China around International Women’s Day, in March, focus on women’s beauty, rather than any promise of parity.