More and more, shoppers today want to know their products were made ethically and sustainably, and clothing is one category they’ve put under particular scrutiny. For decades, the garment industry has served up horror stories of sweatshops, child labor, abuses, and deadly industrial disasters. Brands including Levi’s (pdf), Nike, Adidas, and Gap (pdf) have responded by publishing lists of all the suppliers producing for them. You have to search for them, but they’re accessible.

H&M’s newly launched label, Arket, which is priced slightly higher than H&M and focused more on staple pieces than trends, goes even further. Its website, which went live on Aug. 25, gives the location and name of the factory where each and every piece of clothing was made. It’s a move that pushes transparency, which is vital to help keep corporations accountable, to a new level for mass-market fashion.

But it also raises important questions: What is a shopper supposed to do with that information? And how useful is all this transparency, really?

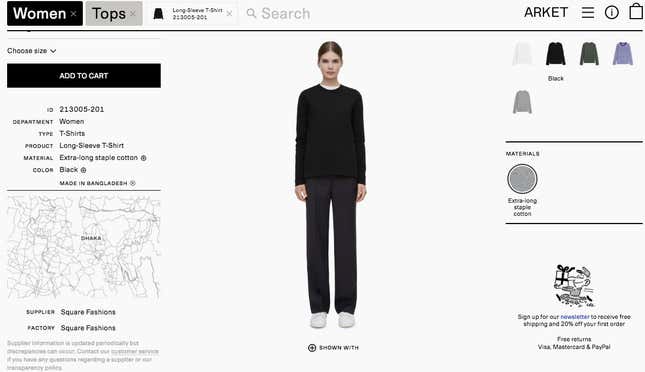

The product description for this long-sleeve t-shirt, for instance, tells interested customers that the shirt was made in Dhaka, Bangladesh, by a supplier called Square Fashions, at a factory of the same name.

That level of detail is exceedingly rare in fashion, and was practically beyond imagining a decade ago. (The site notes that supplier information is updated periodically, but discrepancies can occur.)

H&M says it mandates that all suppliers sign a sustainability commitment (pdf). But factories have been known to violate these agreements, and naming the specific factory doesn’t actually reveal anything to shoppers about whether it offers workers fair pay and safe conditions. That’s the information that’s vital to make an informed decision about the product’s ethical pedigree.

“It doesn’t empower consumers yet,” says Dorothée Baumann-Pauly, research director for New York University’s Stern Center for Business and Human Rights. To do that, she suggests the site link out to “verified third-party data about labor conditions,” such as information compiled by the Fair Labor Association. (The growing basics label Everlane, often held up as the gold standard of transparency in fashion, provides information on its factories, but again, it’s not coming from an independent third party.)

Even if brands linked to such monitoring organizations, though, that information might be hard for consumers to parse. Pimkie Apparels, the Dhaka factory that makes Arket’s Fitted Overdyed Jeans, is listed as “behind schedule” in the database of the Bangladesh Accord, a large group of trade unions and signatory brands, including H&M, that formed to remediate Bangladesh’s garment industry after the deadly Rana Plaza factory collapse in 2013. Pimkie Apparels has corrected nearly all safety issues identified by the Accord, but as of this writing still needs to complete important measures in its factory such as installing a sprinkler system and conducting an electric safety training program.

Should a consumer hesitate to buy those jeans when the factory is largely in compliance? What if a third party found that 80% of fire doors at another factory were up to code? Is anything less than 100% acceptable? Currently, there are no uniform standards on what constitutes an “ethical” or “sustainable” factory, as the Washington Post recently pointed out (paywall).

Another issue in question is whether a shopper can really know that a product was made in the factory listed, not because the company would lie, but because brands themselves don’t always know. The practice of subcontracting is widespread in the garment industry, especially in countries with low-cost labor, such as Bangladesh. Here’s how it works: A factory may take an order from a brand and find that it doesn’t have the capacity to do all the work. Without telling the brand, the factory owner may farm the work out to other factories, which are more often unregistered and therefore the sorts of places where labor and safety violations occur.

As policy, Arket says it closely monitors its factories through its offices in the countries it sources from, and when it does find subcontracting, it takes steps to ensure the facilities are safe. “If a supplier is using a new production unit (i.e. a subcontracting unit), it has to be declared and go through a so called onboarding process,” a spokesperson for Arket says. “This process includes signing our Sustainability Commitment, receiving trainings and being assessed according to the minimal requirements we have defined.”

Arket makes many of its products in China, where subcontracting does occur, though it hasn’t been reported to the same degree as Bangladesh. It sources from Turkey and Romania (pdf) as well, both of which have documented subcontracting.

Notably, the company doesn’t use sourcing agents as go-betweens with factories. It keeps direct contact with its suppliers. That’s a good sign, says Baumann-Pauly, as is H&M’s general practice of using “strategic partners,” basically meaning suppliers they have long-term relationships with. These relationships often mean the brand is more likely to invest in the supplier—if for no other reason than to make it more productive—and less likely to punish it for not hitting a deadline. That reduces the likelihood of labor abuses and the need to subcontract. Conversely, a brand frequently changing its suppliers can be a warning sign that bad practices are likely.

Still, how is the average person supposed to keep informed of all these details, or know what a brand’s relationship with its suppliers is like? Shoppers, especially millennials, are increasingly eager to make sustainable and ethical choices, and the rise of “transparency” is a step toward helping them do so. But it’s not an end unto itself: Transparency can only ensure fair and safe practices when coupled with rigorous third-party monitoring, and when it’s clear enough for shoppers to understand.