This was supposed to be the year Mark Zuckerberg would really start fixing Facebook. It was the CEO’s annual self-improvement project, and, looking at Facebook’s year, it’s probably safe to say that few have ever failed so badly at fulfilling a New Year’s resolution. Scandal has chased scandal, leading to unprecedented scrutiny by governments and the media, backlash from users, and a falling stock price.

What bubbled to the surface this year had been brewing for a long time, and much of it has to do with the company’s very foundation—its ad-based business model built upon a massive data collection effort. But 2018 was without question a tipping point for the Silicon Valley giant and where it goes now is quite unclear.

So, what happened—and what changed?

2018 in bad news for Facebook

Cambridge Analytica

The Cambridge Analytica affair might end up being the most consequential scandal in Facebook’s history, considering how much scrutiny it brought upon the company. It wasn’t an entirely new story in 2018, with several news outlets already having investigated the shady, UK-based data analysis firm that was hired by the Donald Trump presidential campaign. However, blockbuster reports from The New York Times, The Guardian and Channel 4 gave the world an idea of just how much data Facebook had been sharing with third party developers (especially between 2010 and 2014, after which Facebook started blocking off the access), while failing to inform users how lose it was with their information, and how easily outsiders could get away with harvesting it.

Data sharing

In subsequent months, news outlets and lawmakers would uncover even more about how the company built its business not by “selling data” (an accusation its executives love to deny), but by gathering it, bartering it, and giving it away. It gave device-makers like Blackberry access to data; it had partners like Netflix, Spotify, and even Russian search engine Yandex, who were given access to user information while it was walled off for others. The revelations came from The Wall Street Journal, court documents from a US lawsuit seized by the UK parliament, and The New York Times, with the latter making perhaps the biggest splash.While some argue the latest revelations are either overblown or had been known for years, what’s clear is that Facebook has lost control of the narrative and the public’s trust. A big question now is whether these data sharing agreements violated Facebook’s 2011 consent decree with the Federal Trade Commission, which prohibits sharing user data without informing the user, and which could incur potentially enormous fines.

Data breaches

While data sharing is a feature of Facebook’s design, information can also escape from Facebook’s control. In October, the company announced that data—some of it as sensitive as religion or location information—of up to 30 million people was compromised in a massive hack. Just two months later, it turned out that a bug made vulnerable the photos of up to 6.8 million people.

The deadly effects of fake news around the world

We’re living in what some are calling the “post-truth” era, where false information spreads more easily than ever before, and real news and independent media are disparaged as “fake.” This can’t be blamed solely on social networks, but they certainly bear a lot of the responsibility— particularly Facebook, which is so huge that its products substitute, largely or entirely, the internet in some parts of the world. In 2018, the United Nations said Facebook had turned into a “beast” in Myanmar, where it fueled the ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya Muslims by allowing false and hateful information about them on the platform. On a smaller scale, the company was accused of having a similar effect on ethnic strife in Sri Lanka and Nigeria. In India, the company had to alter the way its encrypted messaging service, WhatsApp, functioned, after rumors spread on the app were linked to deadly violence. In the US, the fake news backlash focused on Alex Jones, a notorious right-wing conspiracy theorist. Tech platforms, including Facebook (which followed, rather than led, the effort), banned him from their platforms—but only after helping him achieve enormous popularity and reach.

Continuing fall-out of Russian election meddling

That Russia interfered with the US election and Brexit referendum may have emerged earlier, but in 2018, we’ve heard more about how the country’s operatives were able to game social platforms, particularly Facebook, Instagram and Twitter, spreading false information and sowing division among American voters. Two reports released in December, for example, detailed the breadth of the Russian operation, emphasizing that tech companies did little to help curb the problem. They also showed that Instagram, whose image is still cleaner than that of its parent Facebook’s, was a much more powerful force in the influence efforts than previously thought.

Government scrutiny and threat of regulation

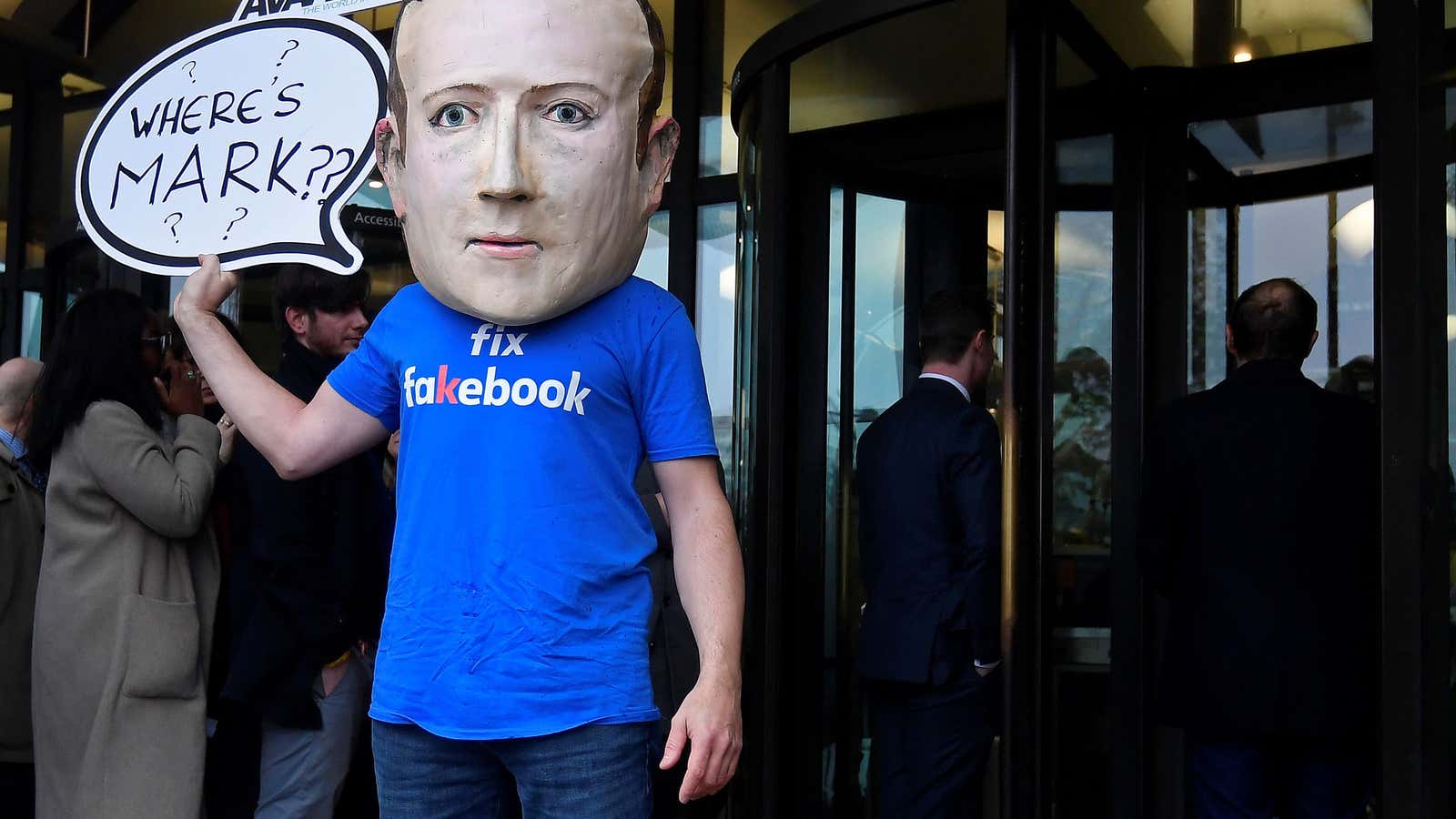

The data scandals and Russian meddling led lawmakers and government officials all over the world to launch investigations, lawsuits, congressional and parliamentary hearings to scrutinize the company’s operations, business model, and past assertions. Facebook executives had to personally answer hundreds of questions, although notably, Zuckerberg avoided facing some of his toughest opponents: the UK’s Damian Collins and his Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee in the House of Commons. Europe enacted a sweeping data privacy law, which had repercussions for the entire tech industry, but the various Facebook scandals helped American lawmakers ramp up discussion of tech regulation in the company’s most profitable market.

Internal turmoil comes to light

Until this year, Facebook was known as a company whose leadership stuck together, with top executives rarely leaving. In 2018, this changed. The founders of WhatsApp and Instagram, Facebook’s most valuable acquisitions, left reportedly due to disagreements over the future of the platforms they started—including concerns over the parent company’s relentless drive toward monetization. Its privacy chief left, as did the head of communications and policy. Zuckerberg, and particularly COO Sheryl Sandberg, had been executives with legions of admirers, but this year saw their public images suffer. Zuckerberg is the embodiment of the company he built, increasingly seen as ruthless and scarily powerful. A New York Times report that detailed Facebook’s hiring of Republican opposition research firm Definers as part of its damage control efforts portrayed Sandberg as the one leading Facebook’s deflection campaign after the Russia and Cambridge Analytica scandals.

So, what now?

Perhaps more than anything else, 2018 seems to have been a moment of reckoning for users and regulators. Facebook’s pervasive and often detrimental role in people’s lives and society as a whole became much harder to ignore. It came down to “the realization that network effects [the economic concept that more users of a product makes it better] and the intention to create technological monopolies by design, on one hand creates immense convenience and immense capability, but it also concentrated power in a way that nobody was prepared for,” said David Carroll, associate professor at Parsons School of Design, and one of Facebook’s most vocal critics, who petitioned the UK government to gain access to his voter data harvested by Cambridge Analytica.

The fundamental thing that Facebook lost this year was any trustworthiness it had left. Carroll noted that in the case of three of these scandals—Russian meddling, Cambridge Analytica, and Definers—”the coverup has been worse than the crimes,” with Facebook continuously shifting in its explanations, hiding crucial information, and downplaying the harms it caused. Add onto that the steady flow of revelations that the company gave away user data, without adequately letting people know, and significant backlash was inevitable. Facebook’s handling of the various bombshells hasn’t helped: it became rote in its responses, repeating that “we need to do better,” while at other times being overly defensive, even condescending in its tone.

Throughout 2018, the #DeleteFacebook movement among users flared up occasionally, the latest spike coming the week before Christmas after researchers released the reports on the Russian influence operation and the New York Times published its data-sharing investigation. Many people, including influential journalists, declared on Twitter (of course) they were deleting Facebook forever. The platform’s power lies in the number of its users, and if they indeed leave en masse—particularly where it hurts, in the United States and Europe, regions that make Facebook the most advertising money—that will be a huge problem for the company, whose investors pay close attention to user counts. The company already lost users in these regions, and we’ll learn in January if more have exited after the latest scandals when it reports earnings. That said, most people can’t just leave Facebook. It can be the only conduit to their family, their hometown, school, the motor of their business, their organization, their support group.

One potential outcome of the Facebook backlash is that regulators make data portability—the idea that you can easily download your data and plug it into a new platform—an enforceable rule, Carroll said. This would make it easier for people to move all their information to new, better platforms, potential Facebook competitors. “It’s the equivalent of when the law was made that you could keep your phone number and all of a sudden you could change cell phone providers. It created the competition in the marketplace that didn’t exist before.”

For this to happen, governments would need to act. And just like 2018 was a year of awakening for many users, it was so for governments as well. In the US, “discussions that people are having at the policy level were unimaginable just a couple of years ago,” Carroll said. And the most significant moments in Facebook’s 2018 saga, Carroll said, were when UK lawmakers and regulators stood up to the company in their investigation of the Cambridge Analytica scandal.

In the end, with more than 2 billion users worldwide, Facebook is too big to fail. If users stay on the platform and its sister apps, either brushing off the scandals or finding they have too much to lose by leaving, so will advertisers, and the money will continue flowing into the company’s coffers. Facebook stock price has fallen by roughly a third since the start of the year, and about 40% from its 2018 peak—but that peak came after the Cambridge Analytica scandal, showing that the company can withstand bad news. Analysts largely still like the company, and believe in its business. People may trust it significantly less, but without an alternative, Carroll said, “we’ll all be resigned to accepting Facebook as a necessary evil.”