How much does Boeing Group, the US’s largest exporter, a top defense contractor, and key component of America’s most popular stock index, influence the federal government’s decision-making?

That’s a lingering question following days of uncertainty over the fate of Boeing’s 737 Max aircraft in the US, after the March 10 Ethiopian Airlines crash that killed 157. On Wednesday (March 13) afternoon, the US’s Federal Aviation Administration grounded the Boeing plane.

The FAA, normally one of the world’s leading aviation regulators, this time followed behind dozens of other governments, who cited concerns about similarities between the Ethiopian Airlines crash and an October 2018 Boeing 737 Max crash that killed 189. The FAA’s inaction came as US president Donald Trump got a personal reassurance March 12 from Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg that plane was safe, one of multiple conversations between the two in recent days, people familiar with the calls told Quartz.

The US government’s handling of the Boeing Max situation “raises the question whether the decision was made based on what’s in the public interest, or based off of relationships and influence,” said Brendan Fischer, the director of federal reform at the watchdog group Campaign Legal Center. Boeing “has a strong interest in government policy and contracting, and seeks to exert influence over government officials in any way possible,” he said.

The company benefits from Department of Defense contracts and other government spending—it makes Air Force One, the presidential plane—for its profits, and gets indirect subsidies from other US agencies, including NASA.

Here’s how the money flows.

Where Boeing’s lobbying money goes

Boeing has spent $275 million on lobbying since 1998 and $15.1 million in 2018, a slight decrease from previous years. They spent more on lobbying in the last Congressional session than any other company in the defense aerospace industry, ahead of global aerospace defense companies Northrop Grumman and Lockheed Martin.

Donations from these lobbyists tend to be concentrated on members of the House and Senate Appropriations subcommittees responsible for the allocation of federal defense money, and have favored Republicans in recent years, as they controlled both sides of Congress.

Lobbyists working for Boeing were active on issues from military spending to how the Export-Import Bank, which provides US companies financing for export deals, functions.

But by far their most frequent topic, according to 2018 filings, was the “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” the Republican and Trump-backed bill that slashed corporate income tax from 35% to 21%. (The bill passed in late 2017, and most of Boeing’s lobbying work on it in 2018 was around “implementation issues.”) Boeing also spent more than $3 million on a bill that would make the Clean Air Act weaker.

Bills where Boeing lobbied, number of Congressional contacts:

Where Boeing’s campaign donations go

As a government contractor, Boeing can’t make big corporate donations to elected politicians. But its employee-funded political action committees and individual employees have long been active in US elections, donating $32.6 million since 1990, according to Center for Responsive Politics data gathered from federal campaign filings. The last few election cycles have seen big jumps in spending, with a slight preference for Republicans.

In 2016, Boeing groups donated five times as much ($229,000) to presidential candidate Hillary Clinton as they did to Donald Trump ($42,500). Most polls at the time predicted a Clinton landslide.

The biggest recipient of Boeing-related campaign donations in the 2018 midterm elections was the “Senate Leadership Fund,” a political action committee that supports Republicans in the Senate. It was set up by allies of Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell, and is run by McConnell’s former chief of staff.

McConnell is married to Department of Transportation secretary Elaine Chao, who oversees the FAA. On March 13, Dan Elwell, the acting FAA administrator, told reporters that the FAA’s decision on the Boeing planes was made “in constant consultation” with Chao.”

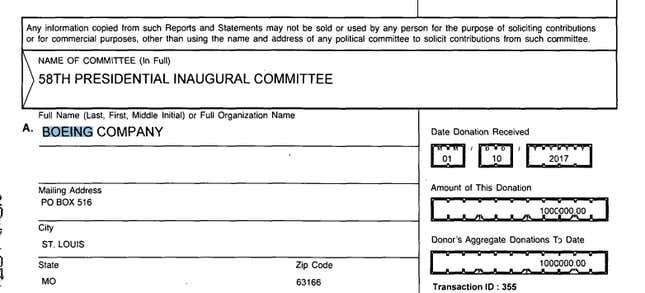

How Boeing helps finance inaugurations

Boeing was among dozens of corporate donors who gave to Trump’s lavish inauguration, which raised more money than any other in history, an estimated $107 million. (Government contractors can donate to post-election activities). Boeing donated $1 million, according to Federal Election Commission documents (pdf, pg. 120):

That was not unusual: Other million-dollar or more donors included Bank of America and Kraft Group, as well as individuals, including SAC Capital’s Steven Cohen and casino mogul Sheldon Adelson. Boeing also gave about $1 million to Barack Obama’s 2013 inauguration fund.

How Boeing helped keep markets up

The Trump tax cuts, which trimmed US corporate taxes across the board by 40%, gave Boeing a $1.1 billion windfall in its 2017 year-end results. Boeing said it would spend $300 million on employee retraining and other worker-related upgrades, but plowed much more back into its own shares, instigating a $20 billion share buyback that helped lift its stock prices above $400 a share in early February 2019 for the first time ever.

Since Sunday’s crash, they have fluctuated between $371 and $399.

The company has an outsized impact on the Dow Jones Industrial Average, the most commonly-used metric of US stock market performance, as Quartz reported earlier. Boeing is the largest corporate contributor to the DJIA, with an 11% weighted share of the DJIA, almost double the next-weighted company.

Despite concerns about the rising US deficit, a “sugar rush” from the tax cuts artificially inflating corporate profits, and economic headwinds, the DJIA and other US indices have stayed relatively strong throughout 2018. Trump has often touted the markets’ strength as an indication the US economy is going gangbusters:

The DJIA closed over 25,000 on Wednesday (March 13), after a brief dip earlier in the week on the Ethiopian Airlines crash, well above the 18,259.60 where it closed the day before Trump was elected in November of 2016.

Shanahan and the revolving door

Washington, DC’s “revolving door” shuffles policy-making experts between government jobs, industry posts, and lobbying groups. Boeing has a particularly active one.

From 2008 until the present, Boeing hired 19 officials from the Department of Defense, according to the Project on Government Oversight.

Trump appointed Patrick Shanahan, a Boeing executive for more than three decades with no military experience, to be deputy secretary of Defense in July of 2017. When James Mattis, the former Marine Corps. general who Trump named Defense secretary, quit with a warning about Trump’s world view in December of 2018, Shanahan was named acting Secretary of Defense, putting him in charge of the Pentagon’s over $700-billion budget.

Before joining the federal government, Shanahan oversaw the 787 Dreamliner and the company’s missile defense system, among other projects. As acting Secretary, Shanahan has “made numerous statements promoting his former employer Boeing and has disparaged the company’s competitors,” according a complaint filed by watchdog group Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington. The group asked the Inspector General to investigate whether Shanahan violated ethics rules on March 13.

Dan Elwell, the acting head of the FAA, is a former lobbyist, and airline executive, who worked for the Aerospace Industries Association which “advocates for effective federal investments” and whose members include Boeing.

Boeing has also hired dozens of former Congressional aides and executive branch officials, including the former Senate Appropriations Committee staffer Arthur Cameron, who is the company’s vice president of federal affairs, and House Transportation and Infrastructure committee aide Amy Smith, who is now director of aviation policy and integration.

Boeing received $21 billion in government contracts in 2017 from the Pentagon, or about 22% of its net revenues. In the second half of 2018, the company was awarded three multibillion-dollar contracts for major Department of Defense aircraft programs, even as it remains behind schedule for other work.

Boeing’s impact

Boeing employs over 153,000 US employees, and has a big footprint in Washington state, California, and Missouri, among others. While some members of Congress demanded that the Boeing Max planes be grounded immediately, lawmakers from states where Boeing facilities are based said they’d put their faith in regulators and the company. “The important thing is that relevant agencies are allowed to conduct a thorough and careful investigation,” said Rick Larsen, a Democrat from Washington, during a hearing March 12.

The company says its activities in Washington are a natural part of its business activities. “As the nation’s largest exporter and a leading producer of both commercial and defense aerospace products, there are a number of significant policy issues at the federal, state and local levels with the potential to impact our business, our diverse workforce, and our supply chain,” a Boeing spokesman said. “Our team is focused on telling Boeing’s story and supporting policies that advance the aviation industry and U.S. manufacturing in the communities where we live and work.”

Read more of Quartz’s coverage of the Boeing 737 Max crisis.

This article originally identified Boeing as a Seattle, Washington company. The company moved its global headquarters from Seattle to Chicago in 2001, but the bulk of its US operations remain in Seattle.