Here are your four apps to understand China’s grassroots consumers

It takes less time than ever to create super apps in China—and the secret is focusing on the country’s smaller and less affluent cities.

It takes less time than ever to create super apps in China—and the secret is focusing on the country’s smaller and less affluent cities.

In the past decade, the three tech giants collectively known as BAT—search business Baidu, e-commerce giant Alibaba, and social and gaming firm Tencent—have shaped China’s internet as we know it today. Thanks to the popularity of mobile phones and computers, they are well-known among China’s 1.4 billion people, offering apps that encompass a range of services unmatched by any single Western tech giant. Yet new forces are emerging to challenge BAT’s dominance.

Earlier this year, the phrase “four kings of the sinking markets” emerged widely in China’s tech reporting to refer to the four apps that have connected most strongly with consumers who have less to spend but who exist in large numbers in China’s “third-tier” and “fourth-tier” cities. Once believed to be of little value because of their limited spending power, the ”sinking market” (a term loosely equivalent to “bottom of the pyramid“) is increasingly active on mobiles, but remains highly sensitive to prices and incentives, according to data consulting firm Questmobile.

The success of the four—online shopping site Pinduoduo, news aggregation app Qutoutiao, video streaming Kuaishou, and crowdfunding app Shuidichou—comes from their understanding of the pressing needs of consumers who don’t belong to China’s highly educated cosmopolitan elites.

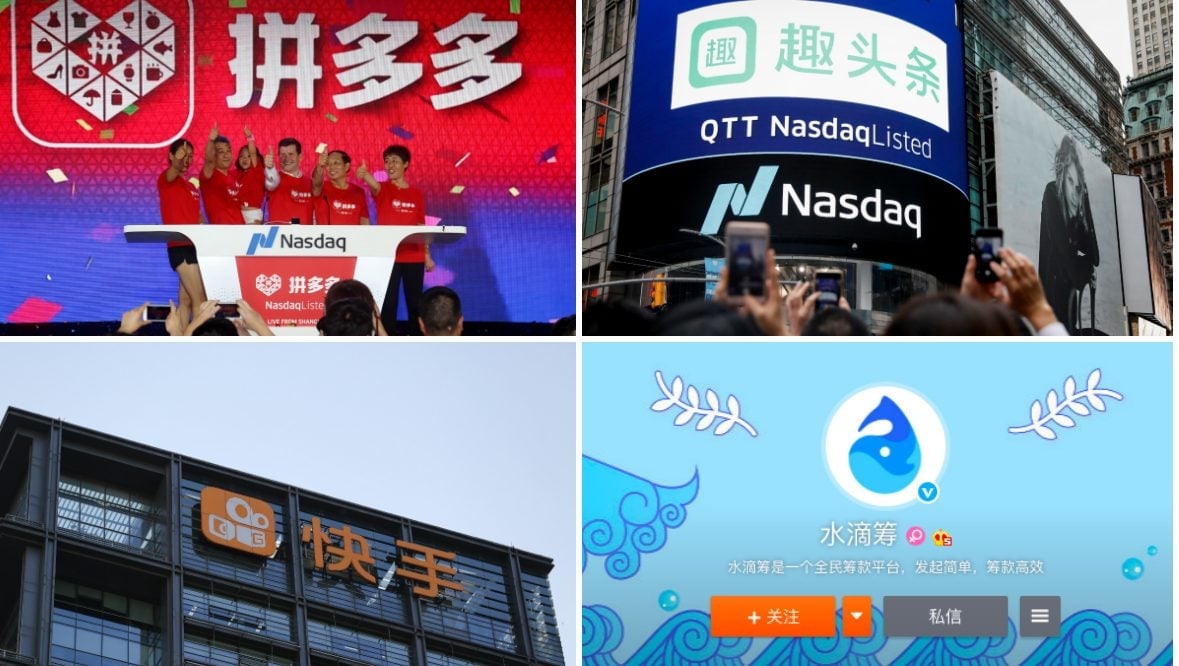

Pinduoduo

Founded in 2015, the app is taking a completely different approach to online shopping than JD.com and Alibaba’s Taobao and Tmall.

“We have observed that consumers in many underserved parts of China are deprived of products that are available in the first-tier and second-tier cities. Due to the complex and multilayered offline retail distribution network, many consumers in lower-tier cities only have access to a limited selection of products, which are often of inconsistent quality,” said Colin Huang, a co-founder of Pinduoduo and a former Google engineer during the last earnings call in March.

The app’s strategy is to make goods as cheap as possible by asking people to shop in a group—an idea conveyed in its name “pin,” or “group together”—to buy everything from clothes, to electronics, to live crabs. The more clicks generated from a user’s shared link to a product on Pinduoduo’s list, the cheaper the good gets.

Now, the company has nearly 300 million monthly active users, growing 74% from the same period last year. MAU is an important measurement for stickiness—reflecting how many users are sharing links and shopping in a given month. The astronomical growth helped Pinduoduo’s gross merchandise volume exceed 100 billion yuan ($15 billion) in 2017, a figure it took JD a decade, and Alibaba’s Taobao five years to reach, according to Reuters. Transactions totaled more than $80 billion in its most recent financial year.

Pinduoduo listed on Nasdaq last year, reaching a valuation about $30 billion in the first day of trading. But its low prices have led critics to wonder if it’s selling the real thing or knockoff products in some cases. Huang said the platform is able to keep prices low by “optimizing the supply chain” (video, link in Chinese). But US trade authorities keep putting the app on the “Notorious Markets” list for counterfeit products.

Qutoutiao

Like Pinduoduo, Qutoutiao, or “fun headlines,” is also a Nasdaq-listed company since 2018. From founding to listing in the US, it took Qutoutiao, which is backed by both Alibaba and Tencent, only 27 months. The app gained popularity by incentivizing users to read content and watch short videos on the app. Qutoutiao said 70% of its 300 million users who have installed the app are from tier-3 cities and below, according to its most recent earnings call in March. The company said that’s only a fraction of the 1 billion population living in those cities, meaning there’s plenty of room to grow.

Qutoutiao’s competing with Jinritoutiao, or “today’s headlines,” owned by Bytedance. Jinritoutiao’s users are mostly young millennials from first and second-tier cities.

Qutoutiao said its AI-backed app could deliver “timely, personalized, and diverse news and information” to audiences, who rely mostly on TV for news. It attracts users by using a so-called “social-based loyalty program.” Every engagement with the app, including reading content, watching videos, daily signups, sharing news generate certain amounts of gold coins on the platform—a few thousands of those translate into cash. A user can also get up to 13 yuan ($1.8) by introducing a new user.

That’s a useful but problematic tactic in keeping users in the app. Qutoutiao’s daily active users have grown to nearly 30 million. A user told state-run news media People’s Daily that the rewards are easy to get at first, but it only gets harder to win those coins later because of more complicated assignments that take a longer time to complete.

Qutoutiao has also faced accusations of copyright infringement. At least 10 complaints had been filed in a Beijing district court in 2018. Qutoutiao was accused of republishing a news publication’s work on its own platform without authorization. The company didn’t immediately respond to questions on the cases.

Kuaishou

The popularity of Kuaishou, or “fast hand,” is part of the video-streaming boom in China. Founded in 2011, the app has amassed more than 245 million MAUs as of June 2018 while its rival, Bytedance’s short-video app Douyin, said it had 300 million MAU as of the same month.

Kuaishou is popular among farmers and migrant workers—young people who haven’t been to college, which is more than 80% of the population, and who are often in poorly paying jobs. They share pranks, and sometimes rather disgusting or embarrassing content, and, according to Shandong University anthropologist Chris K. K. Tan, find a sense of solidarity in being looked down on by China’s middle classes. There are men shoving firecrackers down their pants, while a former construction site worker’s parody of superheroes in Marvels’ Avengers movies had gained over 800 million views as of writing.

Their incentives are simple—making money, and getting to know more people outside of their relatively stable and small communities. Virtual gifts are the most direct source of revenues for users sharing videos. Kuaishou takes a cut of the gifts, purchased by fans watching the videos, then sends the rest to the users.

Farmers can also market and sell products directly on the app, which has helped make the app a first-hand source for commodities traders looking for an edge. For instance, traders in China’s Silicon Valley, Shenzhen, have used videos taken by corn planters to gauge supply and sentiment.

Kuishou said in April that the app had helped “users from impoverished rural backgrounds” generate $2.8 billion in revenue in 2018. It said it has 160 million daily active users as of April.

Shuidichou

Founded in 2016, Shuidichou is built for crowdfunding for people with medical conditions. It’s a platform developed by startup Shuidi, or “water drop,” founded by Shen Peng, a graduate of China’s prestigious Tsinghua University. The platform’s dedication to helping rural families living with a low income came from both Shen’s personal experience and his observations during his time at China’s food delivery platform Meituan Dianping.

Shen said he had passed out for more than 20 hours during a serious burn when he was in primary school. During his eight months in the hospital, he saw people with a relatively average family condition couldn’t access to the best treatments. Later during his time in Meituan in 2015, he noticed that every few weeks colleagues would need to crowdfund for someone ailing or seriously injured in their families. Shen was often the one to organize raising money for his colleagues.

Shen said Shuidichou aims to offer timely help, since people living in lower-tier cities don’t often have good insurance policies. As of June, Shuidichou has covered more than 30,000 villages and towns in 30 provinces, the company said.

Shuidichoud has a standalone app, but the most effective way to crowdfund is via social media like WeChat. Families of the patient post information such as the diagnosis, ID cards, and pictures of the patient in bed and seek pledges for certain amounts of money. People can donate money via the links and pay with their WeChat digital wallet. (Another similar platform is Qingsongchou, a five-year-old crowdfunding platform. It has been targeting users in big cities.)

But these platforms have faced criticism for faking information. State media Xinhua news reported in May that some have faked medical records and found loopholes to game the platform’s verification processes.