Imagine a technology offering that knows your health history—and your family’s, and your neighbor’s. That can alert you if anyone in your building has had Covid-19, or is at higher risk of exposure to it because of their job. That can check whether you have Covid-19, or antibodies to it. That, once there is a Covid-19 vaccine, administers it, and reminds you when you are due for a booster shot. Imagine if it could also check your temperature and blood pressure, make sure you got the latest information about other outbreaks you should be careful about, and be around to answer basic health questions—all free of charge.

Now what if that offering was actually a network of people whose job is to make sure those they serve (often their own neighbors, or acquaintances) are as healthy and informed as they can be, not only about the coronavirus, but all sorts of health issues, including chronic diseases?

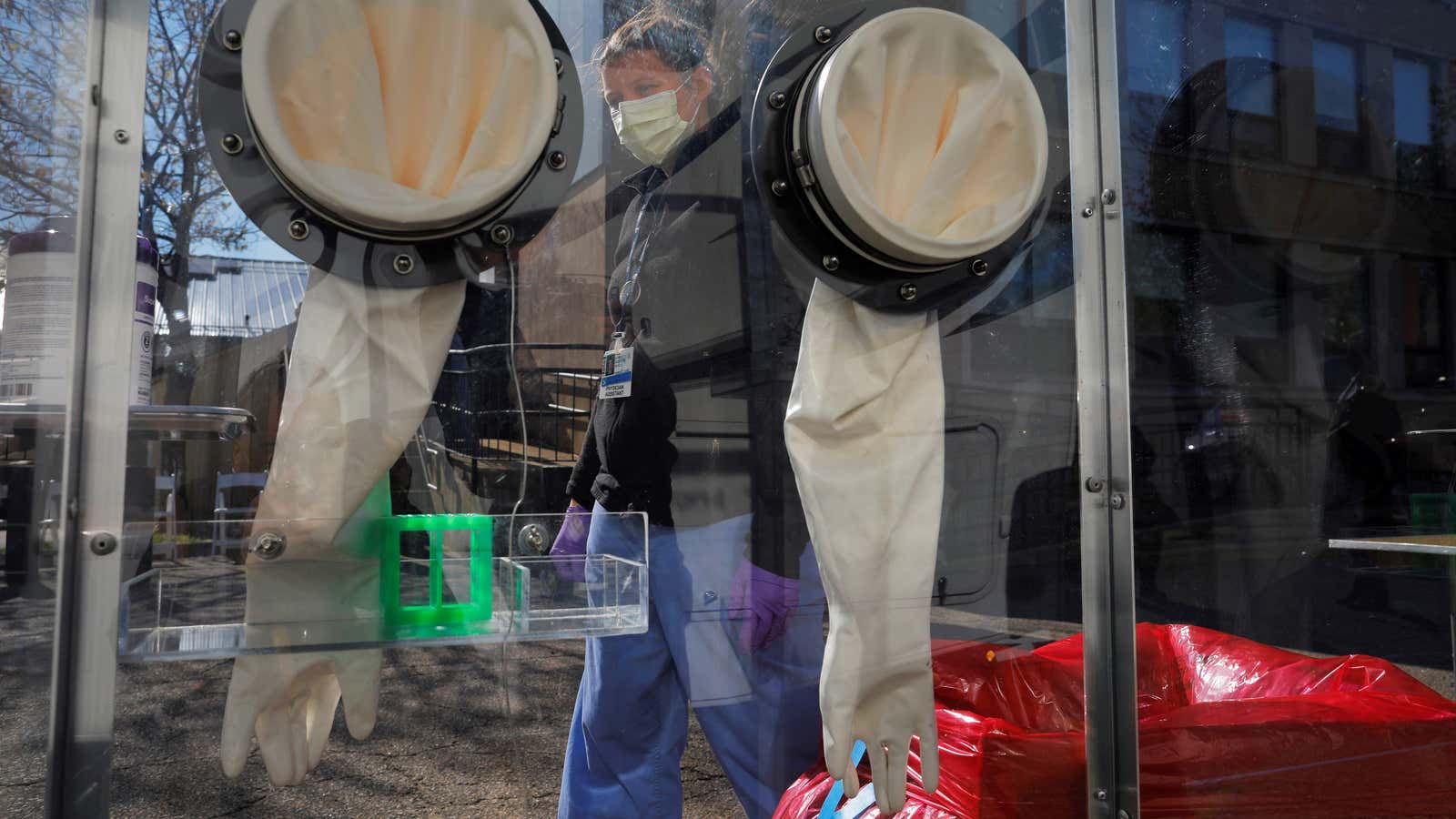

Enter community health workers: members of a community who have basic levels of health training and whose job it is to monitor, inform, and educate. They are one of the building blocks of healthcare in many countries that don’t enjoy the resources of the US yet have developed ways to keep track of people’s health at a local level. They are also widely employed in many rich countries to strengthen the public health system. In Germany, for instance, a country that has been relatively successful in limiting the Covid-19 toll, teams of contact tracers have been deployed to monitor the spread of the virus through the community.

While there are community health workers in the US (about 59,000, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics), they aren’t part of a coordinated federal (or often, even state-level) effort, and only a few states have legally and educationally framed their profession.

Coronavirus might finally change that. Legislation proposed by senators Kirsten Gillibrand of New York and Michael Bennet of Colorado, with support from 11 other senators, calls for the creation of a “Health Force” that would recruit hundreds of thousands of community healthcare workers. What proponents have described as “one of the most ambitious and expansive public health campaigns” in America’s history enjoys the support of public health experts—not only as a way to address the coronavirus emergency and create jobs, but also to strengthen America’s weak public health system.

A new New Deal

Part of a packet of proposals presented last month by Democratic senators to address the health and economic toll of the coronavirus, the health-force plan calls for hiring and training hundreds of thousands of workers currently out of a job. These workers would be paid according to the prevailing wage and have benefits consistent with their status as public employees, a press representative for Gillibrand told Quartz.

There isn’t yet a timeline for the proposal to be officially introduced in the senate.

Under the plan, the community health workers, once they’ve completed required training, would be deployed to tackle the coronavirus crisis by taking on responsibilities like testing and contact tracing. After the emergency, they would continue to be part of state and local healthcare programs, for instance by monitoring a community’s cases of chronic disease, conducting screenings, or giving information on available healthcare resources.

It wouldn’t be the first time America launched such a program. In fact, the plan is in line with the kind of interventions a US administration promoted the last time the nation dealt with a similarly crippled economy, in 1929. Back then, president Franklin D. Roosevelt’s team introduced the Works Progress Administration, which provided millions of jobs in different areas of public life.

Whether through this or other measures, a strengthening of America’s community health system is a key recommendation from public health experts, beyond the current emergency. “We need to scale up a massive community health workers corp to do testing, but also to provide all the other social support that people need throughout the pandemic and into the future,” Gregg Gonsalves, a public health scholar at Yale, told Quartz.

“Imagine you have 100 community health workers come to a small county in Mississippi to do Covid testing,” Gonsalves said, “and half of them end up staying and to do all sorts of other healthcare and social services that need to be done for these communities.”

In the US, the demographics and many of the places that have been hit hardest by the pandemic, both at a health and economic level, already suffered from deprivation and consequent poorer health. Turning attention to maintaining healthy communities would improve the quality of life and health in the long term, making people less vulnerable to future epidemics, too.

Recovery through prevention

The advantage of such models is that they focus on prevention and limiting the recourse to specialized intervention. They cut costs and are effective: There is a well-established correlation between having a strong presence of community and primary care and life expectancy, versus more frequent specialized care.

Enrolling a large cohort of community health workers would help vulnerable areas by providing jobs that don’t require much training, and could be taken up even by people with lower levels of education who are unemployed. It could also be a step toward a fundamental rethinking of the US healthcare system, which is now geared toward treatment (and profit), rather than prevention.

Independent from the Health Force proposal, Gonsalves and Amy Kapczynski, a professor at Yale Law School, laid out in an article the priorities that a cohort of health workers—they call it Community Health Corp—should tackle, starting with contact tracing. They noted that it would be an effective and necessary way to track and protect those exposed to the coronavirus, without demanding that the whole community sticks to shelter-in-place measures. Testing, too, should be scaled up and become part of the corp’s responsibilities.

Community health workers could then turn to information and support, and take on some of the other tasks—from food distribution to emotional support—that have so far been done by volunteers who will not be able to sustain the burden once society starts reopening.

As with tracing and health apps, there would be the issue of privacy, but it might be easier to guarantee that data collected in person is not misused. Gonsalves and Kapczynski also argue in their article that tracing done by a person would be more effective and go to lengths that can’t be replaced by an app. Further, collecting information through coordinated community healthcare workers would help build a database of health conditions (coronavirus, and beyond) and medical records, to track epidemics. This would be a way into the creation of the universal electronic medical record system, which the US has long tried to implement.

Better monitoring would provide enormous improvement in containment strategies, and address the precarious state of data collected so far. Currently, there is still too much uncertainty in the numbers the US is collecting, says Gonsalves, and this is not just limited to the difficulty of accounting for asymptomatic cases. “We don’t even know how many [coronavirus] cases hospitals have at the moment,” Gonsalves noted, pointing out that the margin of error is still high even in data coming from healthcare providers.