It’s a big moment for the little guy on the trading floor.

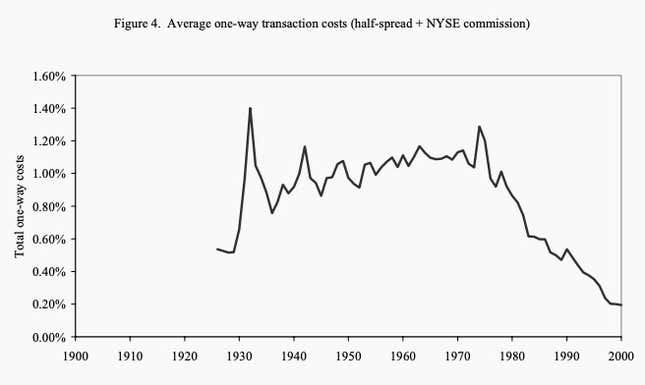

The largest retail trading firms like Charles Schwab, Robinhood, ETrade, and TD Ameritrade began offering no-fee stock trading to retail investors in 2019, and it’s easy to say it changed the stock market. Just look at this chart—and remember that Robinhood, the trendiest retail trading platform, boasted more than 4.3 million daily average trades in March, out-doing all the brokerages below:

But is it safe for retail investors—individual purchasers of stock, not institutional investors like hedge or mutual funds—to be trading more?

A brief history of no-fee stock trading

Purchasing ownership stakes in corporations has always been a wealthy person’s game, but the industry has consistently portrayed itself as expanding access to capital for the little guy, ever since Charles Merrill tried to bring “Wall Street to Main Street” after World War II. Charles Schwab pulled a similar trick in the seventies and E-trade did the same for the tech bubble generation.

Falling commissions have been a marketing and customer acquisition strategy, matched by technical innovation—it’s a lot cheaper to trade stock when it’s a digital, not a physical, product, and brokers passing along the savings can grow their market share.

What’s different about free stock trading today?

But what has enabled commission-free stock trading in recent years is the hunt for an information advantage by the savviest market players—big investment funds that often rely on data-driven algorithms and the fastest electronic connections to trade stocks on a millisecond level. These funds are willing to pay brokerages for early access to their customer’s trades—a practice pioneered by Ponzi scheme icon Bernie Madoff.

For example, if you tell Robinhood you want to buy a share of Apple, they probably aren’t going to the New York Stock Exchange. Instead, they offer the transaction to a market maker like Citadel Securities. In return, Citadel pays Robinhood for access to these orders. Why pay for the orders? It might give the market maker a chance to sell the stock at higher price than if the shares had been bought by a bigger fish, with more negotiating power.

If that hypothetical example doesn’t sound exactly fair, you’ve put you finger on a major market debate. Some say it’s a clear problem: “Brokers face a choice—rebates for themselves or price improvement for their customers,” Justin Schack, managing director at Rosenblatt Securities, an institutional brokerage in New York, told Quartz in 2019. “It’s obvious what’s in the customer’s best interest.”

Other investors argue that relatively small differences in the spread between available bids and offers are worth the trade-off for commission-free trades, and that market makers often offer retail customers better prices than they might otherwise receive.

It can be hard to know the answer—and it’s not a settled question. Brokers are required by law to give their customers the best price available, but lawsuits and financial regulators have questioned investigating how transparent brokeres have been about giving their customers the best deal. Robinhood paid a $1.25 million penalty over the practice in 2019.

But there is another way to think about the risk facd by retail traders: It depends on how they invest.

There’s more than one way to buy stock

The risks of retail trading should be clear: You, the stock buyer, are spending X amount of your day thinking about stocks, while around the world there are tens of thousands of people who are paid huge amounts of money to think about stocks all day long. Who’s going to do better in any game, the weekend warrior or the pro? One reason that Robinhood is getting paid more for its order flow than other trading platforms is that professionals suspect their customers may be less savvy traders than those of other brokers.

The rise in investing during the pandemic—christened the Boredom Markets Hypothesis by Bloomberg’s Matt Levine—has led to horror stories about inexperienced investors losing huge amounts of money.

Many of those investors were not simply buying or selling shares of stock, but instead purchasing more complex securities that investment apps now make easier to access. These investments, called options, involve the right to purchase or sell shares of stock at predicted future price, and can provide higher profits alongside higher risks. But options are far more complex for retail customers to understand, which might be one reason why retail options trades are more profitable for brokers and market makers who buy their orders.

Yet there are strategies consistently recommended by experts to individual investors. Successful retail traders know their limits—trying to time the markets and buy and sell stocks for a profit is out for the amateur. Instead, pay off your debt, then focus on a diversified portfolio of long-term investments across industries and asset classes. Low-fee passive investments in exchange-traded funds is one way to do this. It’s wise to consult a financial adviser who isn’t trying to sell you stock.

Are there other risks and dangers to buying stock online?

Like everything else done digitally, stock trading can suffer from outages and other technical difficulties. Securing financial data from hackers is just the start. When Robinhood’s app went offline amidst major price swings in March, its customers brought a lawsuit. To be sure, that risk can be ameliorated if you’re not trying to time the markets down to the minute.

Online trading may also be screwing with your brain chemistry. The danger of any kind of gambling is the rush is both addictive and makes it harder to rationally calculate odds. Trading apps take advantage of that reality—even without commissions, they don’t make money unless customers trade, and so the user experience is designed to encourage more transactions, “gamifying” an activity that can have incredibly serious consequences.