On New Year’s Eve, 1962, a 13-year-old named Valery Saifudinov took the stage with his band at a party in Latvia’s capital city Riga, then still under Soviet control. In front of a crowd of several hundred factory workers, they launched into covers of songs by artists such as Chuck Berry and Little Richard—Black Americans who, along with forebears like Sister Rosetta Tharpe, created rock ‘n’ roll. The crowd loved it.

“The whole city was talking about rock ‘n’ roll,” Saifudinov, who would ultimately move to California, told the San Diego Union-Tribune in 2012. By the time of that performance, rock records had been circulating in the Soviet Union, despite authorities restricting them. They feared what the music represented: It was new, dangerous, and rebellious—in a word, cool. In the years that followed, rock music would become so popular debates persist over whether it stoked dissent that helped destabilize the Soviet regime.

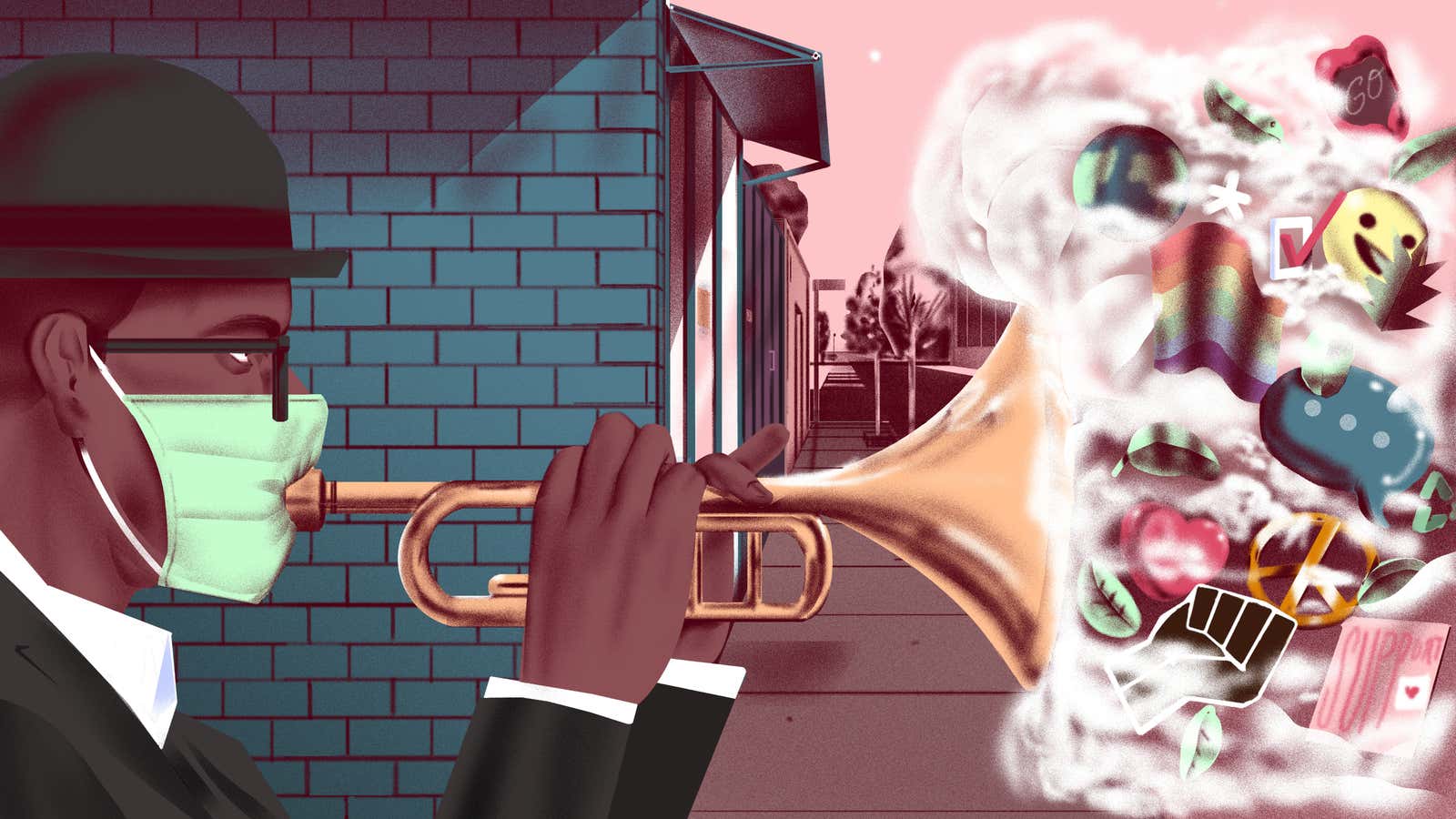

Culture is one of America’s most powerful means of exerting its influence in the world, and in ways large and small, Black Americans have shaped that culture. They’ve held an outsized sway on what the US, and consequently much of the globe, deems cool.

“Black American culture has always been one of America’s greatest exports, particularly throughout the 20th century,” says Mark Anthony Neal, author of multiple books on Black culture and chair of the department of African & African-American studies at Duke University. “It has actually done important labor in terms of connecting global communities, both in terms of the interests of the United States and just people across the globe.”

Where Black Americans have been especially influential is in arenas attuned to style and creativity, which is to say those domains where cool defines trends. That influence is under appreciated, given the power of cool to drive marketing and sales around the world. Companies such as Nike and Apple built their reputations on being cool, and what’s popular in a number of fields often traces straight back to what audiences consider cool.

The Black roots of cool

Sneakers have become a worldwide phenomenon, but the roots of modern sneaker culture trace back to the fashion of mostly Black and Latino kids in US cities. Basketball, whose biggest stars are overwhelmingly Black Americans—one of whom, Michael Jordan, has his name on one of the biggest sneaker brands of all—is another major influence and a growing international success, particularly in China. Streetwear, a clothing style molded by hip-hop after emerging from California’s surf-and-skate scene, has been a dominating presence in fashion.

In music, Black Americans were foundational to several genres widely popular in the US and much of the world, even if they quickly became melting pots of different artists. Blues, jazz, rock, funk, gospel, and R&B are obvious instances, but other forms, such as country and electronic dance music, are similarly indebted to Black innovators. In India, despite its own rich cultural heritage to draw upon, the Bollywood movie industry borrowed from Michael Jackson and his dance moves.

And of course, there’s hip-hop. Historians trace its origin to Clive Campbell—better known as DJ Kool Herc—who was actually born in Jamaica. But it was a party in August of 1973 in the Bronx, New York, where he’s said to have given it life. The city, and the US, ran with it. It’s now the most popular form of music in America and likely beyond. “It’s a hip-hop world” ran a 2009 headline in Foreign Policy magazine. In 2015, Spotify proclaimed it the most-listened-to genre in the world. Hip-hop continues to grow in the US and abroad. In China, where it grew steadily for years, it exploded in 2017 with the competition show The Rap of China. Its influence on K-pop and acts such as Blackpink and BTS is plain.

This cultural impact is all the more remarkable given Black Americans make up a fraction of the US population, rising to just above 13% today after decades of steady growth, and have historically been politically and economically sidelined. The culture they’ve created has in many ways emerged from the fight against these injustices. “The core meaning of cool is some kind of personal expressive rebellion,” says Joel Dinerstein, a professor at Tulane University and author of The Origins of Cool in Postwar America. “To some extent, African Americans are kind of the internal rebel in American culture and always will be, until we either solve the race problem or deal with it.”

The use of “cool” to mean something good, among other connotations, is itself a product of Black American culture. In the 1930s, Black jazz musicians in the US, notably saxophonist Lester Young, credited with coining the term “cool,” began using it to describe a state of relaxed intensity. It went deeper than just a musical style, however. It was an attitude of emotional detachment that rejected the prevailing notion of how Black artists were supposed to perform on stage, as Dinerstein details in his book. Entertainment such as minstrel shows where Black performers were expected to amuse white audiences with a smile had been the paradigm, and just one in a larger array of racist rules Black Americans had to follow. But jazz musicians rebelled against this idea.

Rebellion is at the core of cool

Rebellion has remained central to cool ever since, and this streak of stylish defiance continues to animate Black Americans’ contributions to fields such as music and fashion. “One of the things that Black folks have always had ownership of is style: the way they walk, the way they talk, how they wear their clothes,” says Neal. “All of that was an element to show individuality and even community.”

The Black American influence has been greater than simply making products that reflect their own feelings of rebellion. Neal points to the influence the US civil rights movement had on anti-colonial movements in other countries, and on artists such as Nigerian Afrobeat pioneer Fela Kuti. Dinerstein notes how hip-hop has given artists in countries from Brazil to Japan a template to speak about their own issues in their own languages. “It provides the tools for people’s rebellion wherever they are,” he says.

It’s a testament to the creative strength of a cultural product when it can take on a life beyond its creators, but problems arise when companies and individuals use that to their advantage. Corporations from record labels to sports companies such as Adidas and Nike have at times used Black culture for their own gain while failing to include Black people in their enterprises and profits.

Rather than being seen as an extension of Black people and how they are often forced to live in the world, Black culture is often treated as a commodity that can be bought and sold, Neal says. It allows society to embrace Blackness without having to actually embrace Black people, a form of hypocrisy Black Americans have long contended with. A way to start addressing the issue, he adds, is for corporations to diversify their leadership teams so more non-white voices have a say. In industries such as fashion, that work has been slow.

But social media is allowing Black creators direct access to an audience, giving them more control and ownership of their products. The long-term ramifications of that shift remain to be seen, but according to Neal, it’s helping shift the power balance between Black innovators and companies. “Young Black kids have Instagram and TikTok and all kinds of other social media to really present themselves in ways that are undiluted and unmediated,” he says. “They don’t need a public relations firm anymore to tell folks they’re at the cutting edge of cool.”