China’s new leaders, who take the stage in Beijing’s Great Hall of the People on Nov. 15, are taking over a country that is looking healthier. By September, the economy had slowed for seven straight quarters down to quarterly growth of just 7.4%. But October was a different story. Here are all the good things that happened last month:

- Exports increased 11.6%, year on year.

- Industrial production growth rose 9.6% year on year (9.2% the month before).

- Retail sales growth accelerated 13.5%, in real terms.

“China bulls” have leapt on these data. Frederic Neumann, co-head of Asian Economic Research at HSBC, says that while it is misplaced to expect China’s economy to return the heady double-digit growth levels it experienced up until last year, “we can expect an acceleration from here.”

However, some economists are even more than usually skeptical about the data, given that China has been holding its 18th Party Congress and a once-a-decade leadership transition. As London consultancy Capital Economics wrote in a note last week, given that the rosy data “have been published while the Party Congress is in session, some sceptics have questioned whether they can be believed.”

So what’s really going on?

The industrial output looks real…

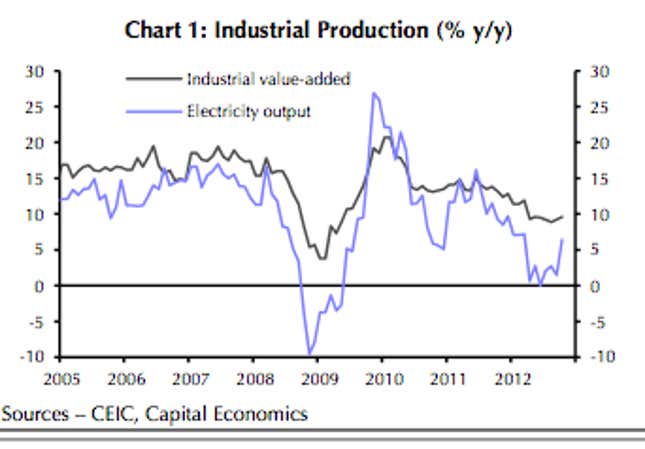

As this chart from Capital Economics shows, electricity consumption in China rose alongside the industrial production statistics in October, suggesting factories really are getting more active. These data do not always correlate. Last year’s electricity statistics made the government figures appear questionable.

…but it’s basically a stimulus.

The pick-up in industrial activity is only small, and mostly comes from government investment. Capital Economics points out that most of the October growth came from “heavy industry”, which in China includes energy companies and iron and steel makers. This growth, in turn, is coming from lavish government spending on infrastructure and public works. The Ministry of Railways, for example, is set to spend $32 billion on new projects by the end of December.

We’re not so sure about those exports…

While not outright questioning the recent robust export data, Barclays economist Jian Chang said in a Nov. 9 note that export orders at the Autumn Canton Trade Fair, a huge trade show in the southern Chinese city of Guangzhou that retailers visit to buy Christmas stock had seen a “mid teens drop” compared to the same event last year. She forecast “likely headwinds for exports in the coming months.”

…and the private sector is lackluster.

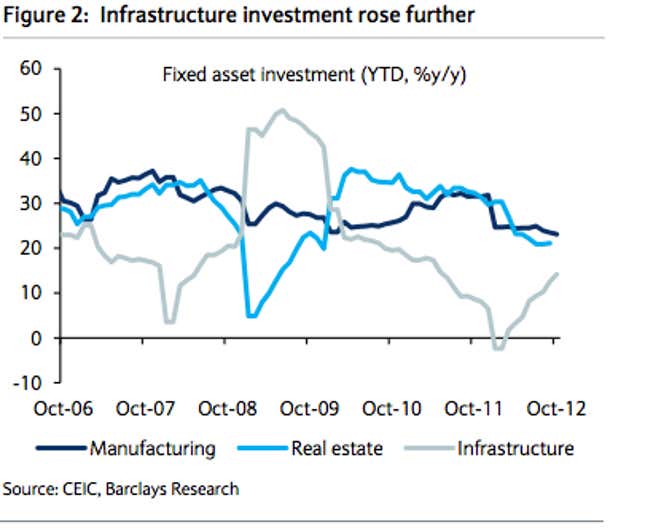

Economists never quite agree on the figure, but China’s GDP is composed of approximately 50% fixed asset investment. As a rule of thumb, fixed asset investment means government spending on state projects such as new railroads, toll roads and airports. It appears to be responsible for the lion’s share of October’s good economic data. By contrast, real estate, which is largely a private sector business, is not doing well. According to Capital Economics, construction starts fell 6.4% in October on last year.

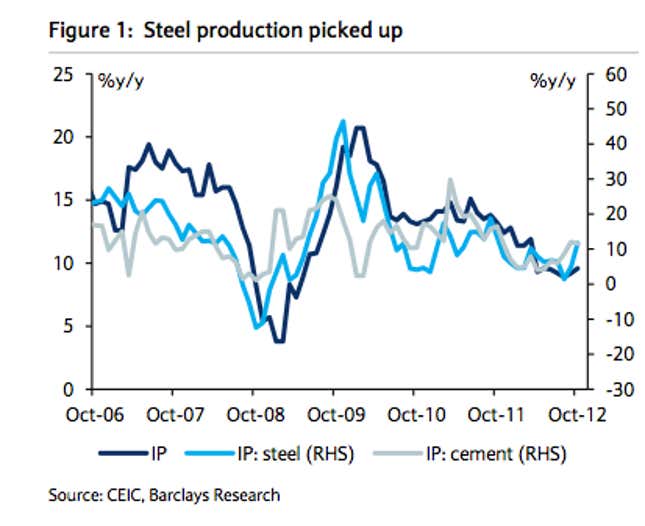

For another view of how state and private-sector spending can diverge, look at how steel production in China has picked up…

…while investments in the real estate and manufacturing sector (this would include exports) are declining.

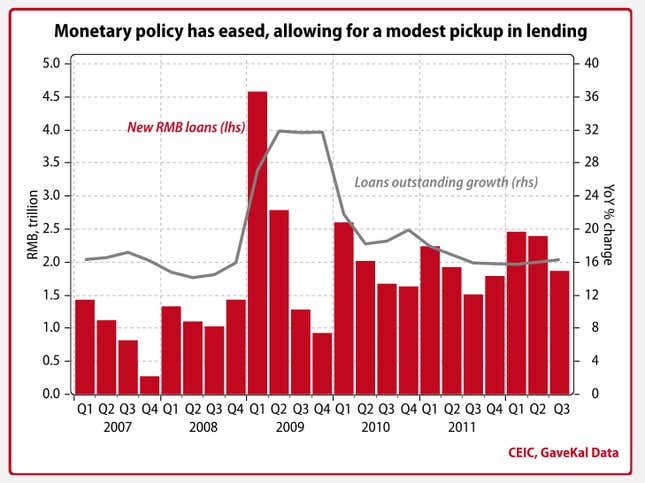

A credit bubble is looming…

The government is funding its infrastructure spree by flooding the economy with credit (again). Consultancy GaveKal Dragonomics wrote in a note that by the end of this year, “China’s total debt ratio will rebound in 2012 to close to the 2010 level of 207% of GDP.” Economists at bank Standard Chartered have issued similar calculations. China’s state-owned banks are already nervous about bad debts, having funded Beijing’s massive economic stimulus in 2009-10 by lending to earlier infrastructure projects that were sometimes unnecessary.

…and it’s not bank credit…

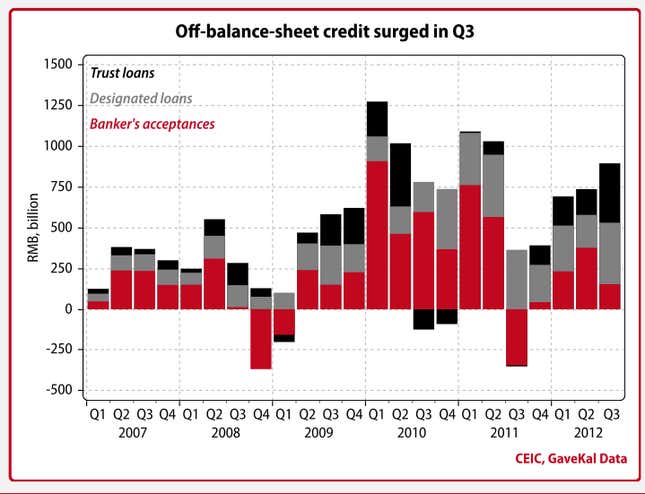

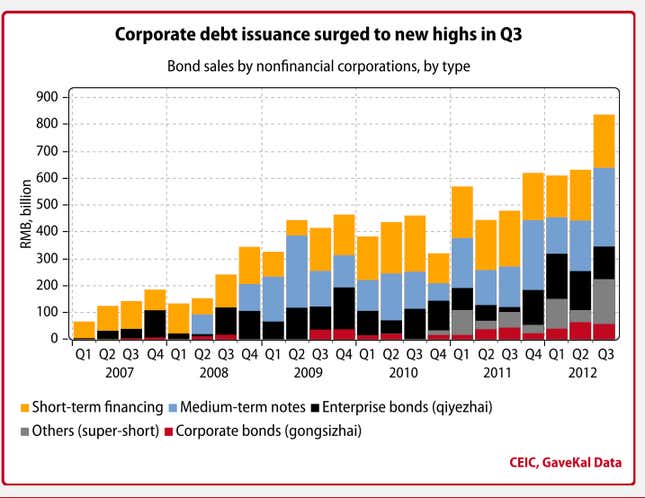

This time around, bank funding is being replaced with bonds and shadow banking products. Local governments in China, who often take responsibility for new public works, gobbled up a lot of bank debt during the last stimulus. They are largely responsible for banks’ bad debts. So this time, municipal borrowers and the state owned construction, steel and infrastructure companies who are investing in stimulus projects are increasingly issuing bonds, as the below charts show.They are also turning to the so-called “shadow banking system.” Yet shadow banking is just another name for off balance sheet loans Chinese banks make, often by collecting the capital to do so from retail investors and calling the loans wealth management products.

…but the banks are caught up in it anyway.

Though Chinese banks aren’t directly making the loans for all this infrastructure spending, they’re buying or issuing a lot of the bonds and shadow bank debt. GaveKal says the biggest issuers of corporate bonds in China are now state-owned enterprises, followed by local governments. And according to the Financial Times, the biggest investors in these corporate bonds are Chinese state-owned banks (paywall).

This chart shows how straight bank lending in China does not appear to be on a worrying trend:

But this one outlines the explosive growth in the shadow banking sector:

And here is the growth in bond issuance:

There are white elephants everywhere.

Explosive credit growth is probably bad news for the economy. Jack Rodman, the head of Beijing bad loans consultancy Global Distressed Solutions, believes Chinese banks are not getting repaid for much of their economic stimulus loans. Anecdotal evidence would suggest he is right. China has a glut of new, debt funded and probably unnecessary aluminum smelters, airports, shopping malls and even some empty new cities. And these were built before the latest stimulus spending began.

Rodman wrote in a client presentation he shared with Quartz that while the Chinese government “may rely on continued credit expansion to ever-green loans, this does not mitigate the fact that banks do not receive payment.” He added that the evergreening (i.e., continuous rolling over) of bad loans via bonds and shadow banking products will “crowd out new lending, further weighing on GDP growth.”

China’s banks look like Japan’s used to…

In 1997, Rodman worked for Ernst & Young, advising Japanese banks on how to manage bad debt sales. Then he moved to a similar role advising Chinese banks. (He now works independently advising investors such as hedge funds.)

Rodman sees Chinese banks repeating mistakes Japanese lenders made. In an email, he writes: “”Japan from 1985 to 1993 rolled-over and ever-greened loans in the same manner China is [now].” He continues that “Chinese banks “force borrowers to access shadow banking”, to pay off loans. And then “re-instate the old loans (with accrued interest) a few days later.”

Japan also had shadow banking in the 1980s, which as this Bank of Japan report (pdf. p4) outlines, “partially accelerated” real estate bubbles and “seemed to amplify credit cycles.”

…and so does China’s economy.

As Peking University finance professor Michael Pettis points out here, Japan in the 1980s “grew at extraordinary rates fueled by a credit-backed investment boom funded at artificially low interest rates.” He adds:

“Although for many decades much of the investment may have been viable and necessary, by the 1980s investment was increasingly misallocated into expanding unnecessary manufacturing capacity, as well as fueling surges in real estate development and excess spending on infrastructure.”

That sounds familiar.

Chinese officials aren’t as clever as they might seem.

Or at least, not as clever as financiers make them out to be. As Michael Schuman, Time magazine’s man in Beijing, writes, businessmen and bankers “paint China as a wonderland of quick transport, quick decision making, and quick-witted government officials.” But China could repeat Japan’s mistakes. The Daily Telegraph’s Ambrose Evans Pritchard recalls hearing similar claims about clever Japanese officials and the superiority of that country’s economic model in the 1980s:

China rebounded in 2009 because it blitzed the system with fiscal stimulus worth 16pc of GDP, and because credit growth running near 30pc each year had not yet run out of momentum. It was a short-term cyclical effect. Similar claims were made about Japan a quarter century ago when it brushed off America’s 1987 crash with deceptive ease. We all had to listen to lectures from the Left on the virtues of Japan’s dirigiste MITI model, with its intimate cross-holdings of banks and corporate Samurai.

China needs to rebalance its economy…

The great hope is that China can move beyond stimulus to develop high-tech exports, and a strong consumer sector that looks more like Indonesia’s. The buzzword is “rebalancing.”

The way to do this, judging by how Taiwan and South Korea transformed their exporters from metal bashers into high tech firms that paid higher wages, is for China to develop its private sector. That means helping private firms get priority for subsidies and bank loans at the expense of state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which dominate the economy. State-owned firms tend not be innovative because they are often monopolies with guaranteed incomes. As the World Bank urged China in 2009 (pdf, p. xix) “[i]t is of strategic importance to China to invest in technological capacity building of the emerging private sector, which is now populated by young SMEs [small and medium enterprises] run by inexperienced owners and managers operating with relatively low technology.”

…but there’s little sign that it will do so…

China’s new leaders don’t look especially enthusiastic about rebalancing. Hu Jintao, the outgoing president, said in his opening remarks at the 18th Congress that China’s state owned enterprises would continue to expand. If he is predicting the course his successors will take, that augurs badly. Hu’s successor, Xi Jinping, is unlikely to transfer loans and subsidies away from state owned enterprises. Xi is supported by the so-called “princeling” faction of the Party, whose members have gotten rich from close associations with SOEs.

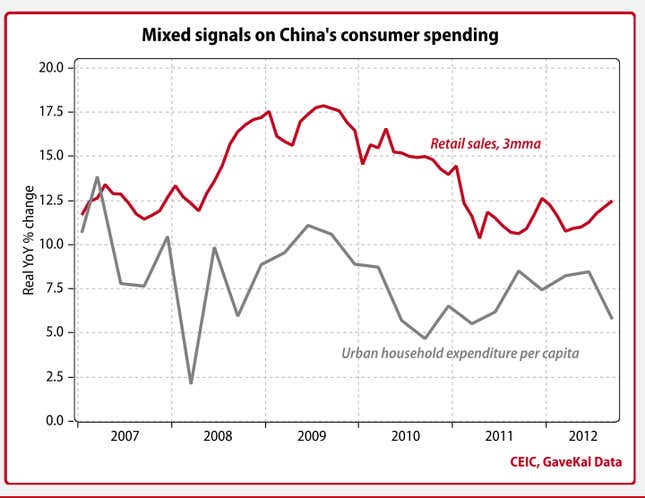

…nor that it has done so up to now.

Retail sales have been going up. Some take that as a sign that consumers are spending more—i.e., rebalancing is taking place. But GaveKal points out in a recent research note that the retail sales figure includes government and corporate spending. As this chart shows, spending by individual households has fallen sharply so far this year, despite the economic stimulus—a sign that stimulus funds are going straight into the coffers of government-owned companies, passing the ordinary folk by.

Savers get a raw deal from banks…

The deposit rates savers get at Chinese banks are usually negative in real terms, because they are below inflation. That helps the state-owned banks keep money flowing to state-owned enterprises, but individual depositors pay. While in the US, low interest rates encourage people to charge more shopping trips, meals out and holidays on their credit cards and remortgage their homes to fund a good lifestyle, Chinese people do not like borrowing money. As Peking University’s Pettis explains, “The general wealth effect in China, then, is mostly about the impact of interest rate changes on the perceived value of bank deposits.”

…so household spending keeps falling as a share of GDP.

According to Standard Chartered, the artificially low rates savers get at Chinese banks cost Chinese households 1.6 trillion yuan (HK$1.98 trillion) last year. Tom Holland writes in the South China Morning Post (paywall) “That’s 3.5 per cent of GDP: a huge drain on household income and consumption.” He also outlines how household income—as opposed to spending—is becoming an ever smaller part of the economy. He says: “last year [2011] household income was just 45 per cent of GDP, down from 56 per cent in 1990.” As for household spending, it’s even lower, according to independent China economist Andy Xie, who calculates that it is about a third of China’s GDP. He says, “The world has never seen such lopsided distribution between the state and household sector.”

So what could the new leadership do?

Pettis suggests the government could increase interest rates, allow the yuan to appreciate and allow wages to rise.

Yale economist Stephen Roach argues in the New York Times that China must end what he calls the “financial repression” of its people by raising the savings deposit rate and creating a welfare state.

In fact, minimum incomes are rising, according to Communist Party-controlled newspaper the Global Times. But to get around the wage increases, some Western manufacturers are using robots in their Chinese factories instead of people. For wage rises to be sustainable, then, China desperately needs to build a services economy, produce higher value exports, or both.

As Roach writes in his NYT column:

“China must provide a comprehensive set of regulations aimed at opening up its embryonic services sector. The second largest economy in the world cannot afford to have a services sector that is only 43 percent of its gross domestic product—well below the percent shares in Asia’s other major developing economies such as India, Korea and Taiwan.”

He adds:

“Services-led growth offers China many benefits. It provides the infrastructure for consumer demand—especially in neglected distribution industries such as wholesale and retail trade, domestic transportation and supply-chain logistics. Services require 35 percent more jobs per unit of Chinese output than manufacturing and construction, allowing China to absorb surplus rural labor while growing more slowly.”

We’ll be keeping a close eye on what Xi Jinping, incoming premier Li Keqiang, and other officials say in their first days and weeks in power.