Through much of the 1990s and early 2000s, Infosys ranked up there with the Taj Mahal as part of any foreign dignitary or business luminary’s India itinerary. To drive home the software developer’s significance, the trees lining the company’s sprawling Bangalore headquarters include placards with the names of the people who planted them: Bill Gates, Michael Dell, the prime ministers of Japan and Norway, among them.

Infosys represented what was possible in a liberalized Indian economy. The country’s first food court in an office setting. The first Indian company to list on the Nasdaq. Office parks modeled on a college campus (down to the Domino’s Pizza on site). Tom Friedman’s best-selling The World is Flat was inspired by former CEO Nandan Nilekani who said: “The playing field is being leveled.”

Now, Infosys is just fighting to stay in the game.

On April 12, the company warned that its growth in the upcoming year will be a sluggish 6-10%. Infosys shares tanked on the news, a tumble they continued today.

The company’s actually been slipping for some time now. Initially, the easy scapegoat was economics. Labor costs are rising in India, removing the competitive advantage that outsourcing offered in the first place. Infosys, like many of its peers offering software services, has been setting up in cheaper and more strategic places, including smaller cities within India, Mexico, the Philippines, and even Atlanta, Georgia. Then there’s the theory known as decoupling, the idea that the US sneezed, and Infosys caught the cold. With its fortunes so closely tied to western markets (nearly two-thirds of Infosys revenue came from North America last year), the damage was inevitable.

Except, by all accounts, the US economy looks to be rebounding. Nasscom, a key tech and outsourcing trade group in India, predicts growth of 12-14% for the year to March 31. Similarly, tech stocks on the Bombay exchange outperformed benchmark indices in the latest quarter. In a note to clients last week, Cowen & Co. analysts Moshe Katri and Avishai Kantor squarely placed the blame: “We believe Infosys’ issues continue to be company-specific rather than industry-specific.”

What happened?

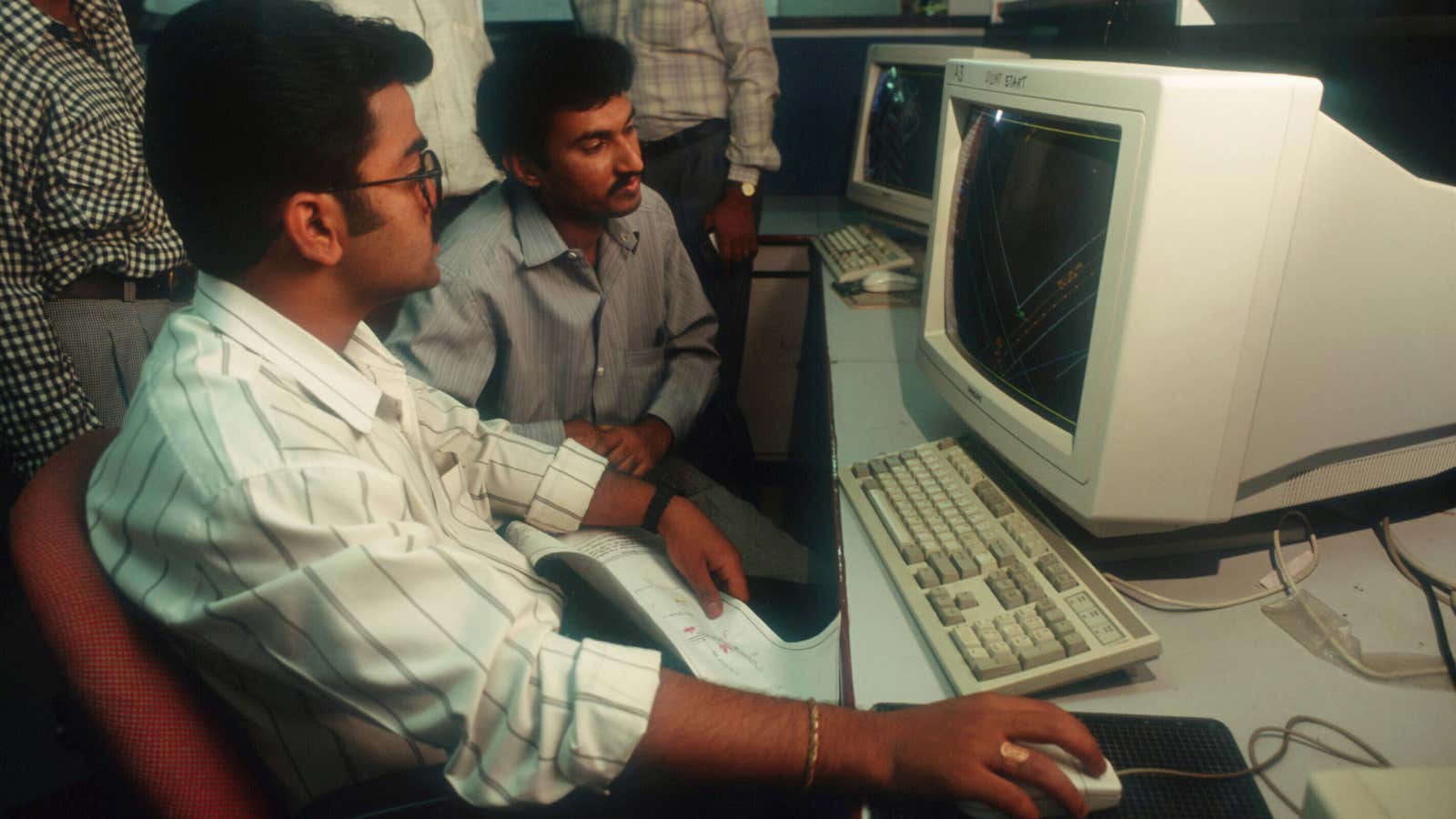

I made the business reporter’s pilgrimage to Infosys’ Bangalore headquarters in 2001, exactly 10 years after India embarked on reforms that propelled its economic turnaround. Over and over, workers would marvel, “You just don’t feel like you’re in India at this company.”

The irony of Infosys’ current predicament: it has become the classic Indian company it tried so hard to eschew.

Its biggest error was giving each co-founder a “turn” to be CEO. Infosys was founded in 1981 by seven guys who famously borrowed money from their wives to get started. Today, it employs more than 150,000 people. One of the brightest spots of India’s recent growth is the sincere embrace of meritocracy: caste and lineage don’t matter if you work hard enough. Yet for its entire history Infosys has been run by one of those guys; current CEO S.D. Shibulal is the fourth founder to ascend to the top spot. Not all of them are equally capable. That’s why the company initially worked so well. Many bases and skill sets were covered.

Its current leadership feels somewhat reminiscent of the way India’s private sector has historically been run: as clubby, chummy, family-run corporate dynasties. The first two CEOs—Narayana Murthy and Nilekani—were media darlings for a reason. They appeared revolutionary in an economy creaking open, with the potential to create opportunities for so many. Outsourcing expert Sudin Apte wrote in Quartz of how Infosys leadership failed to evolve with the company’s growth:

What we are seeing today is a transformation from essentially an entrepreneurial experiment that started 25 years ago—wherein Infosys’s charismatic founders managed everything—to a more mature, traditional, and institutionalized organization expected to be run by professionals.

Coincidentally, Infosys’ recent announcement revising forecasts came nearly two years to the day after the departure of Mohandas Pai, who held many roles during his 17-year run including CFO. But because he never held one title—founder—he’d never hold another—CEO.

When he left, he was heading up human resources, which in itself speaks volumes about how much tech companies must value their manpower. The philosophy is best articulated in former HCL president Vineet Nayar’s book, Employees First, Customers Second. In most industries, the CFO’s move to human resources would be considered a demotion. But the management of the people in an outsourcing operation is key: They (and their skills) are the commodity being sold.

Cognizant of this reality, Pai had an aggressive plan to upgrade the technical and management skills of Infosys’ workforce. It tackled the attrition and employee exodus that has plagued Infosys and the entire sector, really, but also might have better prepared the company for the shifting needs of the global marketplace, from the days of coding for Y2K bugs to the current obsession over Big Data. In an interview with Business Today, Pai alluded to why he was leaving: “The founders have been dominating the management stream,” he said. “We discussed the re-organisation earlier but decided the time was not opportune.”

His message fell on deaf ears. In an August interview with CNBC, Shibulal indicated that his successor would also come from inside the company. This morning, the Mint business newspaper reported that Infosys’ board is seriously reconsidering, saying “a more thorough hunt that includes candidates from outside too is something high on the agenda.”

There have been other missteps—a failure to diversify and innovate—but until Infosys addresses its leadership void and succession philosophy, any drastic redirection is moot. The outsourcing giant once helped revolutionize the global management of human capital. Its own management should never have been exempt from those lessons.