Your name and mobile phone number could be in the hands of a company you’ve never heard of—all thanks to a stranger you met at a party.

“Caller ID” apps—like China’s WhatsCall, Sweden’s Truecaller, and Israel’s Sync.me—promise to identify spam sales calls from telemarketers, insurance companies, and the like. But according to a Nov. 21 report from Hong Kong’s FactWire, those three apps have also created searchable databases of some 3 billion phone numbers and associated identities. By looking up a number in these databases—which include mobile numbers for Google co-founder Larry Page and Hong Kong’s much-loathed chief executive, CY Leung—anyone who has downloaded these apps can discover who that number belongs to.

A name and matching phone number might not seem like much personal information, but it is arguably the most important data point you can get about a person. A mobile number signals where you’re from. It can help someone access your Facebook page, your Google account, or any other service bound to SMS verification. Phone numbers are often tied to bank accounts, credit cards, and other financial services. Merely obtaining your name and phone number is enough for a hacker to read your text messages and listen to your phone calls.

Making matters worse, not everyone in the Caller ID databases has handed over their phone number directly. Many were collected through other users, who gave the apps access to their contacts when registering.

The potential impact is enormous: Truecaller claims to have as many as 90 million monthly active users, while WhatsCall has at least 100 million. There are smaller competitors too; Whoscall, Hiya, and CIA App among them.

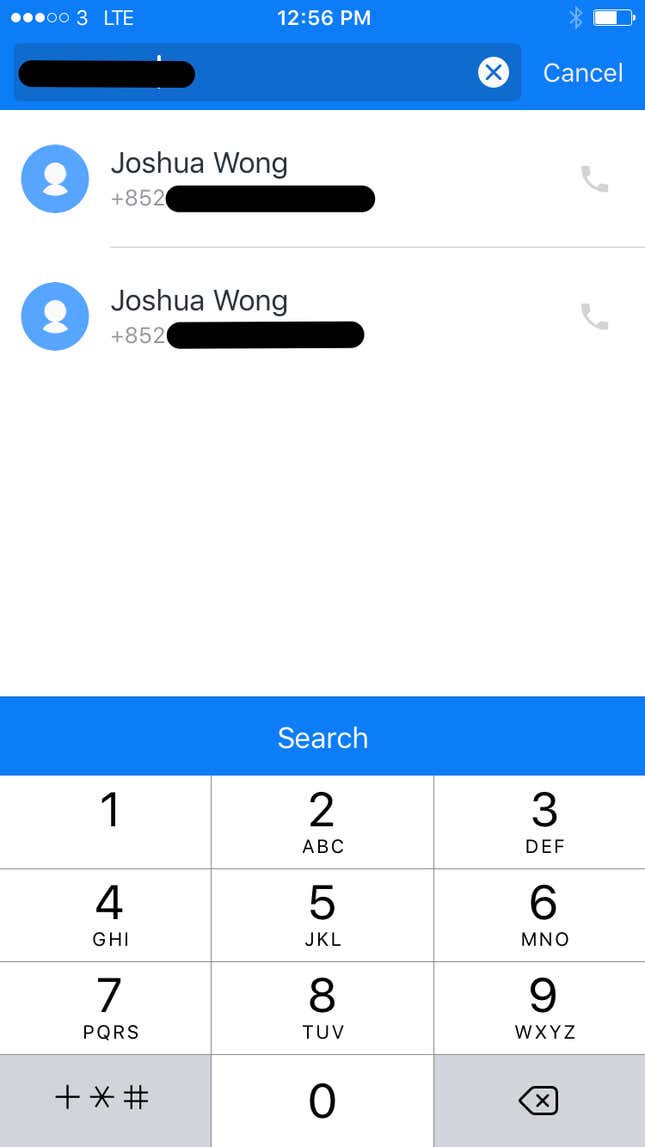

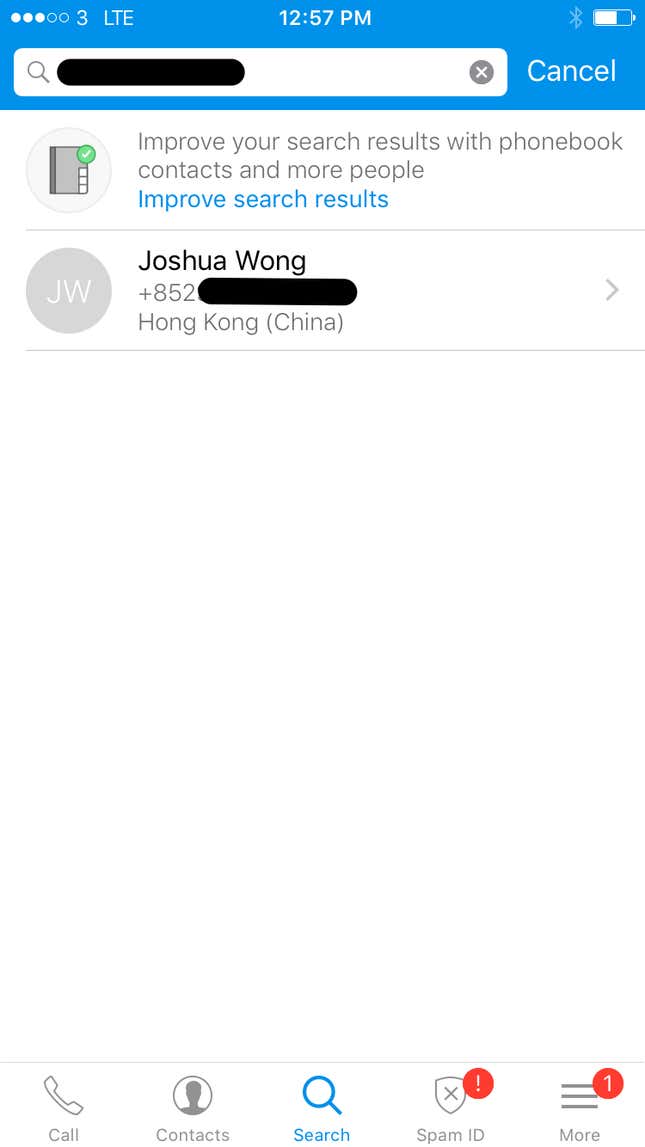

Quartz Asia decided to test how extensive these databases are. (To search, you need to download the apps and register; Sync.me also requires an extra fee.) We didn’t have CY Leung’s personal number, but we did have one for Joshua Wong, a leader of Hong Kong’s pro-democracy Umbrella Movement, and a numer for activist-turned-legislator Eddie Chu. Wong turned up on both Truecaller and CM Security, while Chu showed up only on Truecaller.

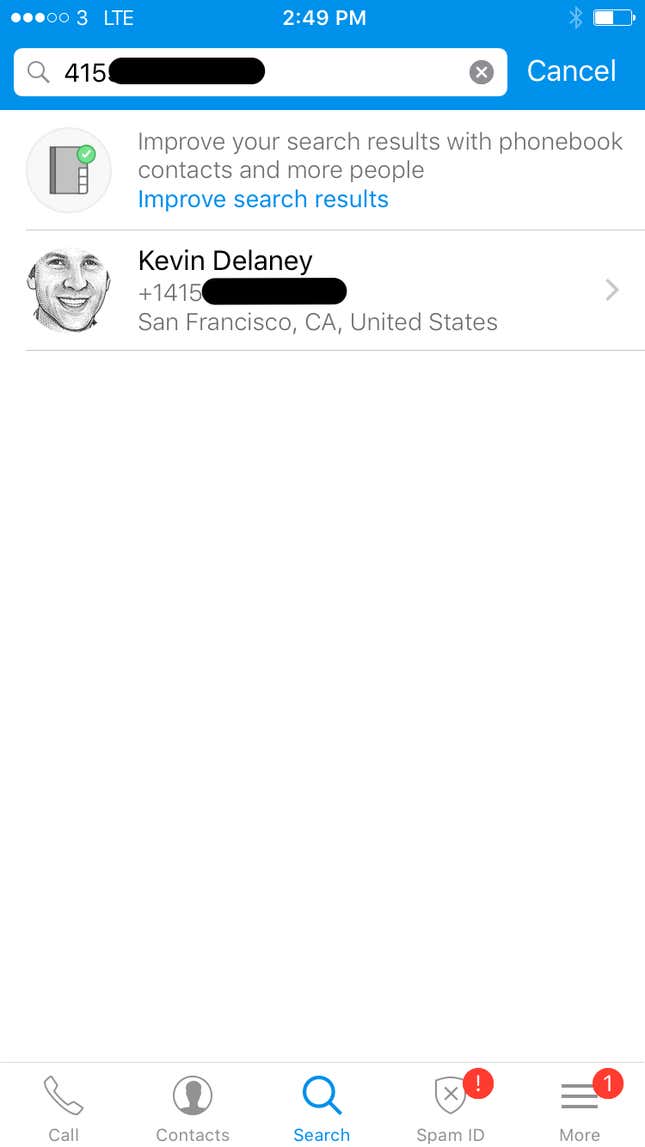

Truecaller also correctly identified the phone number of Quartz editor in chief Kevin Delaney, who has never downloaded Truecaller.

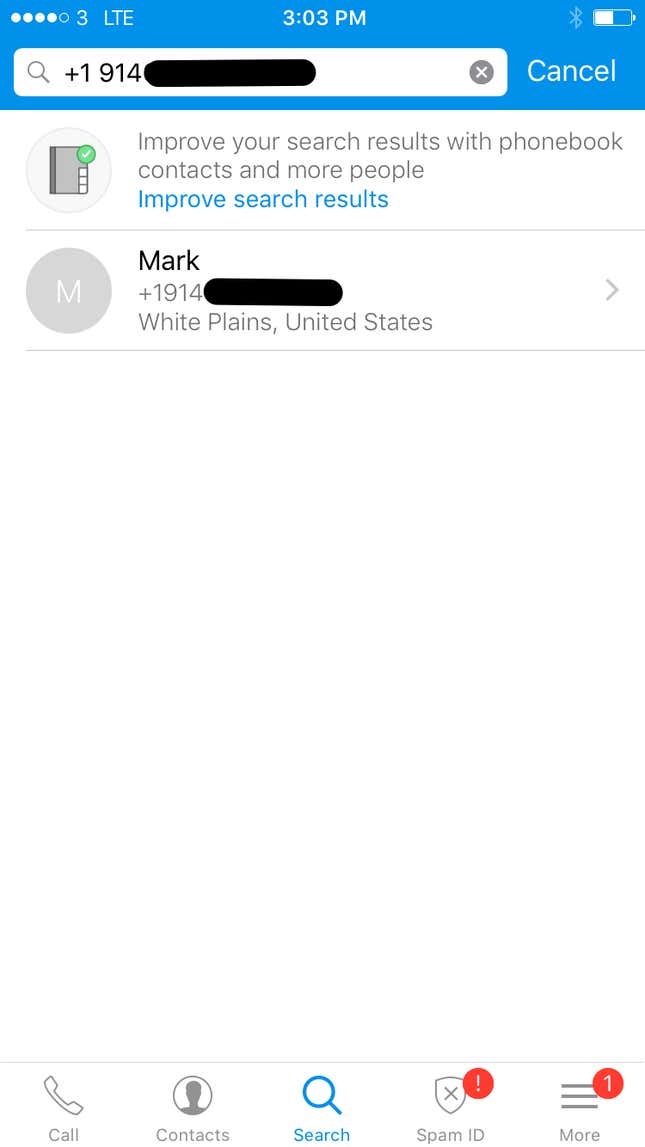

An outdated number Quartz had for Mark Zuckerberg lists “Mark” under White Plains, New York, Zuckerberg’s place of birth.

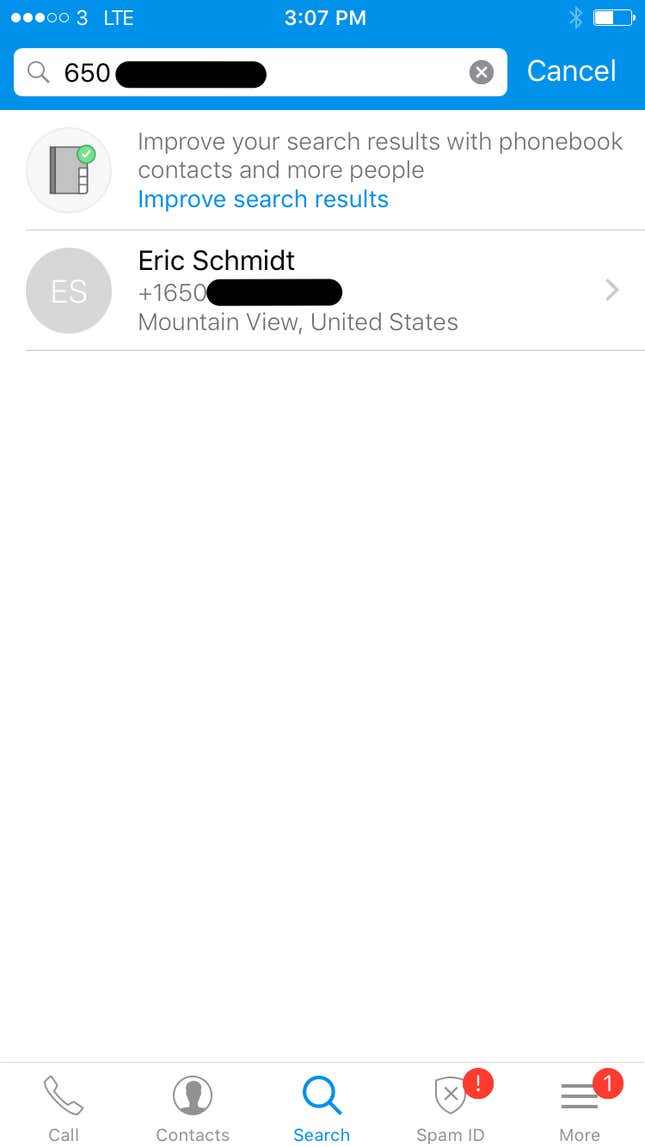

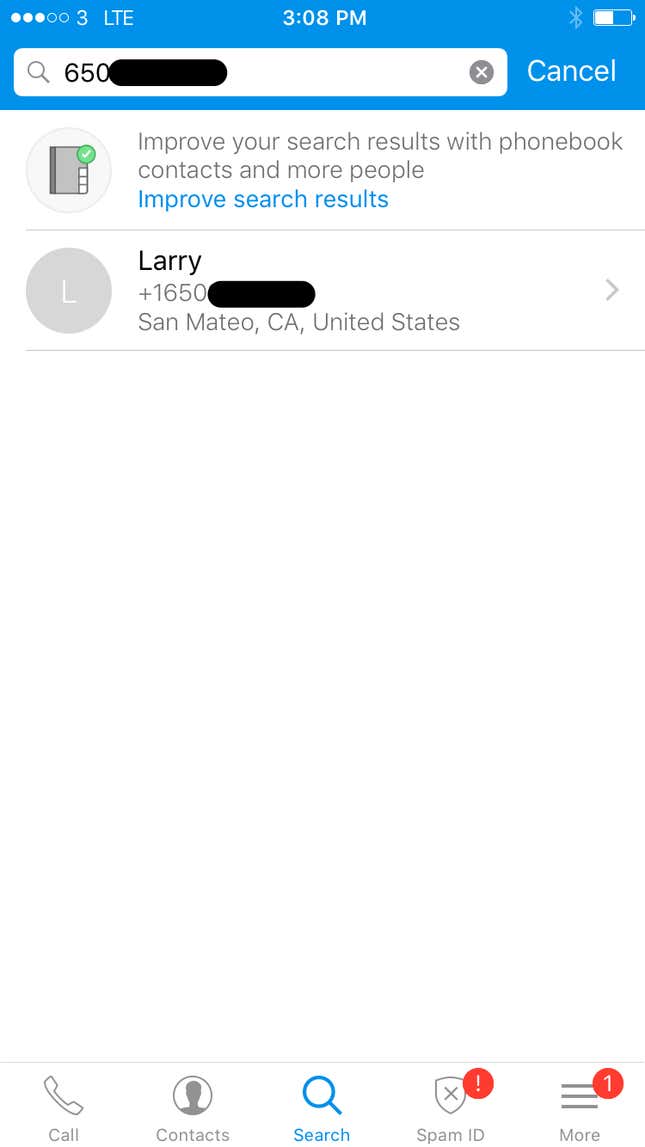

Numbers we had for Alphabet chairman Eric Schmidt and Google co-founder Larry Page matched up with their names too.

Of course, the apps won’t make it any easier to prank-call Hollywood stars or Silicon Valley CEOs—the “reverse search” feature means you need to know a number to confirm its owner. But these apps clearly know the value of the info being gathered; their privacy policies make clear an intention to collect everything and share much of it.

Truecaller’s app is allowed to “collect, process and retain personal information from You and any devices You may use in Your interaction with our Services,” according to its privacy policy. “This information may include the following: geo-location, Your IP address, device ID or unique identifier, device manufacturer and type, device and hardware settings, ID for advertising, ad data, operating system, operator, IMSI, connection information, screen resolution, usage statistics, device log and event information, incoming and outgoing calls and messages, times and date of calls, duration of calls.”

The app’s terms of service offer an important addendum: “If you provide us with personal information about someone else, you confirm that they are aware that You [sic] have provided their data and that they consent to our processing of their data according to our Privacy Policy.”

Sync.me’s privacy policy says users hoping to access its search feature “will be asked to provide the names, phone numbers and email addresses contained in your device phonebook directory, in order to enhance your searchable directory. For security reasons, please note that if you access this feature we will only collect the names, numbers and email addresses of your contacts, and any other information stored on your device phonebook directory (e.g. physical address) will be filtered and not be stored or used by us. This information will be aggregated on our directory and allow you to perform numeric search and identify incoming calls against this directory, which contains the contacts’ information of users who permitted the aggregation of this information.”

Truecaller and Sync.me did not respond to a request for comment.

WhatsCall’s policy says parent company Cheetah Mobile won’t share one’s contact list ”to any third party without any legal reason,” but a Quartz search for Schmidt’s phone number still called up his name. When asked to comment, Cheetah Mobile said it had disabled its “reverse search” feature:

While our intention is to maximize call identification function, it’s unfortunate that this was misused. Therefore, CM Security will temporarily shut down the “reverse look-up” function. However, user feedback and fraud library search will remain functional. We apologize for any inconvenience we may have caused for some users after the temporary closure of reverse look-up feature.

Users (or non-users) who wish to remove their personal data from the company’s database can contact whatscall@cmcm.com.