After 2016, all we know about music is that we have no idea what’s next

Amid a mess of spiny trees, starlight, and early hints of an intermittent drizzle, Justin Vernon stepped on stage and plowed through a dozen songs no one in the crowd of thousands had ever heard before. “That’s the end of side A,” Vernon—the bearded, soft-spoken one-man founder of indie folk sensation Bon Iver—announced, halfway into the live release of 22, A Million. And added, sounding pleased: “It feels super cool playing it live for the first time.”

Amid a mess of spiny trees, starlight, and early hints of an intermittent drizzle, Justin Vernon stepped on stage and plowed through a dozen songs no one in the crowd of thousands had ever heard before. “That’s the end of side A,” Vernon—the bearded, soft-spoken one-man founder of indie folk sensation Bon Iver—announced, halfway into the live release of 22, A Million. And added, sounding pleased: “It feels super cool playing it live for the first time.”

His audience, myself included, remained quiet throughout his hour-long set at Eaux Claires, a woodland fairytale of a music festival set up by Vernon and a few other indie artists in rural Wisconsin this August. No one knew Bon Iver would be releasing its first album in five years, there—not until the news came out mere days before the campgrounds opened. Song titles were announced in real-time, via an app designed specifically for the festival.

Yet the lack of promotion was, in and of itself, a stunning promotion.

Music in 2016 has gone through a dizzying amount of change. One of its biggest revolutions? The death of the album. As the era of physical records and digital downloads fades from view, and streaming platforms like Spotify and Apple Music take over as dominant modes of consumption, people are finding fewer reasons to listen to entire albums all at once—making it all the more vital for artists to present them in attention-jolting, unexpected ways.

By the end of 2017, it’s likely the once-traditional album drop (feat. pre-release hype, bonus tracks, and everything else one used to expect) will be a thing of the past entirely.

“Played out”

“The surprise is gonna be a surprise,” the ever-enigmatic Kanye West promised on a radio interview prior to the drop of his last record, The Life of Pablo. “Release dates is [sic] played out.”

True to his word—for once—West rolled out Pablo in a disjointed scramble in February: first at a fashion show in Madison Square Garden, then as an exclusive (well, sort of) release on fellow rapper Jay Z’s streaming service Tidal. The record was accompanied by a series of physical pop-up clothing shops, and its digital existence allowed it to be later updated with a litany of little tweaks and changes, including adding new songs.

All intentional, of course. “In the months to come, Kanye will release new updates, new versions, and new iterations of the album,” Def Jam, West’s label, explained (paywall). “An innovative, continuous process, the album will be a living, evolving art project.”

Some weeks before Pablo, Rihanna debuted her eighth album Anti—also as more or less a surprise, and also as a Tidal exclusive. Shortly after, Beyoncé released her newest album Lemonade, which arrived following a TV special aired on HBO in the US; later came Frank Ocean’s Blonde (really, he dropped two albums, one visual, to get him out of his record deal) accompanied by its own hard-to-find magazine; Solange’s A Seat at the Table, Kendrick Lamar’s surprise album of outtakes, and a handful of others.

All as surprises. It easily became the year of the unexpected album release.

All we got / so we might as well give it all we got

Catching people off their guard is a shallow gimmick, though—and that’s all it is.

The albums that have seen staying power in 2016 also come with an extra dimension to them: Rihanna’s Anti was a psychedelic, genre-quitting departure from any of her previous discography. Beyoncé’s audio-visual Lemonade wasn’t so much a music record as a series of miniature would-be box office hits. Pablo had the novelty of ongoing updates. Et cetera.

There’s also something to be said for the rebirth of the concept album this year, or perhaps an updated version of it: the in-your-face, I’m-here-making-a-statement album.

Leonard Cohen’s You Want It Darker is meant to serve as a nine-track ode to the now-late singer’s obsession with death and religion; pop singer Zayn Malik pointedly put out a solo album on the exact date he quit One Direction a year prior; A Tribe Called Quest reunited to record some of the best political protest music the world’s seen in a while yet; British rock band The 1975 gave its sophomore album the awkward/aggressive/unforgettable name I Like It When You Sleep, for You Are So Beautiful yet So Unaware of It.

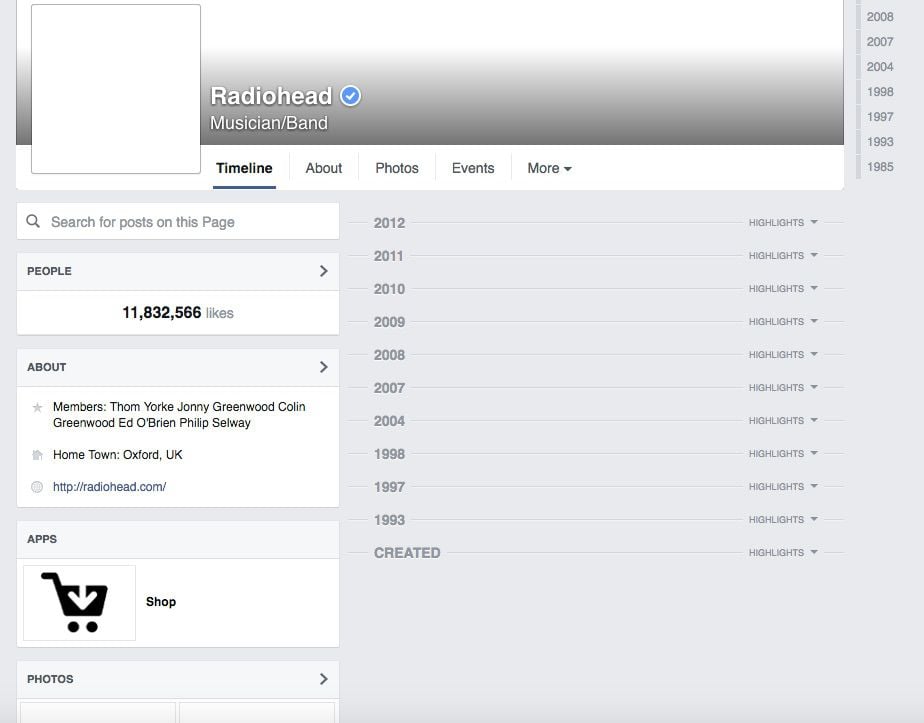

And then there were the musicians opting for album releases full of not surprise, exactly, but something both akin and completely opposite. When Radiohead dropped A Moon Shaped Pool in May, fans knew it was coming—because the band, in the days prior to the release, played an intricate anticipation game that began with erasing themselves from the internet.

Critics noted symbolism in the tease: It was Radiohead’s “attempt at re-emerging from the ether,” to start anew as “a band that has surely wondered how to stay restive as its legacy has grown.”

Beyond that, though? It was something new.

That’s the key word here, the one that describes all the conscious efforts of many artists, in 2016, to make their releases stand apart. Musicians—true ones, anyway—have always done their best to differentiate their work from that of others past and present. (Some would argue that’s one of the most imperative points of art.) Now they’re doing the same with the way their music comes out, too.

Drake’s Views turned heads when it became the first album to reside exclusively on Apple Music. Aside from netting the artist a rumored $19 million, the Apple deal snagged the attention of the music industry, which was alarmed to see such a surge in people streaming and not buying albums, and of fans, who became all the more eager to listen to a record that was only available in a certain corner of the internet. The same happened with Lemonade, with Pablo. Exclusive albums—the problems of piracy that they cause, aside—were radically new. They were exciting.

Chance the Rapper’s Coloring Book became a weirder variant of that when it dropped on streaming services, solely. The album—already interesting for being self-produced and coming out unattached to any record label—topped charts without selling a single physical copy or digital download, and is now the first streaming-only album to ever be nominated for a Grammy. (Chance has also made his fair share of other surprise moves this year, including popping up out of nowhere alongside Bon Iver at Eaux Claires.)

The greatest, the greatest, the greatest

Sia came out with the pop behemoth This Is Acting in January. She followed up with a deluxe version—in September, far later than is usually appropriate, essentially making it a second album release altogether. This time around, the record boasted collaborations with Lamar, Sean Paul, and a smattering of other acts; while not a total departure from the original set of songs, musically, This Is Acting‘s deluxe version’s delayed timing made it a novelty all over again, and no doubt helped to pull in some all-important new streams.

One of the biggest tracks on the second release then also appeared, a new product once more, as a Hillary Clinton endorsement.

Why stagger a single album in installments? The same reason for bartering exclusive release deals, or adding a dozen music videos: to pique interest. To draw attention. Because at this point, it’s necessary.

“Formats and distribution models have always played a practical role in shaping what music can be to a listener,” Pitchfork’s Jillian Mapes observed, recently, in a study on the modern evolution of the pop album. “Major labels and their superstars [are] finding more ways to game the system.” That game, the ultimate end goal of which is to snag more listeners and more plays and more money, begins with the release of music itself.

For new music albums, it’s been a year of ceaseless—dare the word be used?—innovation. Beyond anything, 2016 blew out the rules, the conventions, of releases, making it so that, when it comes to pushing out new tracks, artists are no longer limited by anything that previously curtailed them, or their work.

Not even death.