Middle-class Chinese are risking jail to recoup billions lost in a “zero-risk” government-backed investment scheme

Two steamed buns and a bowl of boiled cabbage, carrots, or unpeeled potatoes—Qian Xiaohong had boring food options in jail.

Two steamed buns and a bowl of boiled cabbage, carrots, or unpeeled potatoes—Qian Xiaohong had boring food options in jail.

Aside from eating, Qian whiled away her month in a Beijing detention center wondering how she ended up there. When she finally emerged, in November 2015, she had shed 5 kg (11 lbs) and, in her own words, “gained mental trauma.”

Before her imprisonment, the 30-year-old saleswoman was among a group of investors planning a protest outside the headquarters of China’s top securities regulator in Beijing. They had all lost significant amounts of money, in some cases their life savings, by investing in the Fanya Metal Exchange—what turned out to be one of China’s most notorious financial scams in recent years.

Police detained Qian and others on charges of “gathering crowds to disturb public order.” The detention periods ranged from a month to a year.

“I was innocent in the past,” Qian said in a recent interview by phone from Beijing. “I thought everything was full of sunshine, until the detention overturned my ideas.”

It’s been nearly two years since the Fanya Metal Exchange froze the $6 billion it received from investors—mostly retail investors, numbering about 220,000 across the country. The government remains reluctant to begin a long-pending fraud case of 20 Fanya executives (link in Chinese) or find other ways to help victims recover their money.

By now, Fanya investors know their calls to hold accountable the local officials and state banks linked to the fraud will unlikely be answered. No one knows for sure whether they’ll ever get back their investment, or even a small portion of it. While they await a long-delayed court trial of the Fanya executives, many of them have taken matters into their own hands by organizing protests, looking for legal aid, and spreading the news about their plight.

They are now in an endless cat-and-mouse game with authorities. Fanya investors—many of whom are well-educated members of the middle class who didn’t previously care about politics or civil rights—have become unlikely protesters, petitioners, and even prisoners. Their plight highlights the Communist Party’s inability to handle China’s chaotic financial system—and its hostility toward civil society.

Investors-turned-prisoners

Investors who put their life savings into the Fanya Metal Exchange usually did so for the same reasons. They believed that the exchange, which claimed to be the world’s biggest trading platform for rare metals, was too big to fail. The government in Kunming, where Fanya is based, approved its setup in 2011. The state broadcaster frequently promoted it. The biggest state banks recommended its products to customers. Such endorsements made the investors buy into Fanya’s flagship product, which promised “zero risk” and an annualized return as high as 13%.

Since April 2015, when Fanya froze their accounts, these investors have come to realize that they have no one to depend on but themselves. For months after the freeze, the police did not look into the case. The state regulators charged with protecting investors remained silent. Then after a seven-month investigation, last August Kunming police finally announced (link in Chinese) that 20 Fanya executives, including the founder, would be prosecuted for “illegal fundraising.” The police also said they were handing over the case to the local procurator, which would present the case in a criminal trial.

To this day, no trial date has been set.

Though they are mostly ignored, Fanya investors have learned to take every chance to “make a scene.” One of their favored methods is to hold loud, constant public protests. But this often comes with the risk of imprisonment.

Tan Yaoming is among the investors-turned-protesters. In the past two years, the 35-year-old Shanghainese has traveled to Beijing for demonstrations several times. He frequently joins local protests outside state banks, financial regulators, and other government agencies. In April, he and around 300 others rallied at a branch of the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), in Shanghai’s central Xuhui district, holding up placards about the organization’s role in the Fanya case. Though not every protester bought Fanya’s product from ICBC, Tan explained, a public protest outside a major state bank—China’s largest—is a good way to let more people know about their plight. “We just wanted society to look at our evidence,” he said. “Justice will prevail in the end.”

Tan was arrested at the scene and kept under administrative detention for five days for “disturbing social order.” Never had he imagined he’d be jailed in his lifetime, Tan said, as he’s always been a “law-abiding citizen” and “honest person.”

After his release, Tan decided to keep on protesting. It’s hard to concentrate on his job as a mechanic, he said, because the salary is too small compared to his extended family’s investment of 3 million yuan ($440,000) in Fanya. ”I’m confused about the future of my whole life… I only want my money back,” said the father of a 10-year-old.

Not every protester has lingered on. In December, 50-year-old Wang Yue, a once-vocal protester in Shanghai, said that he’ll no longer participate in any activities related to Fanya—at least for now. That followed his release from a 30-day detention for his role in leading an earlier protest at the Yunnan government’s representative office. (Kunming, where Fanya is based, is the capital city of the southern Yunnan province.)

During the protest, Wang and dozens of other investors broke into the government office through a fire exit and snatched away the cellphones and laptops of three officials who’d been avoiding them. The police made charges against two of the protesters based on these actions. Wang said, without giving details, that his detention has “struck too heavy a blow” to his family, and even affected his son’s job.

“I have realized that the party represents everything,” he said. “Our rights-defending has too small a chance of succeeding.”

Big brother is watching

The crackdowns on Fanya investors might end with arrests at protest scenes, but the investors are continuing their resistance where it began: on the internet.

WeChat and QQ are China’s two most popular messaging apps. In hundreds of chat groups on the apps, Fanya investors regularly plan protests, share ordeals, and provide updates on their cases with each other. But these peer support groups are closely monitored by the government, investors say. As a result, many of them have had weird, unpleasant conversations with police seeking to talk them out of disobedience.

One of them is Mao Lina, a 30-year-old financial manager from central China’s Henan province. Writing in several WeChat groups in April 2016, she called upon fellow investors to occupy the residential complexes, canteens, kindergartens, and schools run by the Kunming city government. Because street protests are “neither painful nor itching” to the officials, as she described it, she wanted to give authorities and their family members some real problems. “If they don’t let us live a good life, we won’t let them either,” she wrote.

One night about a week later, at around 9pm, a police officer from Mao’s neighborhood paid a visit to her mother’s place, where Mao’s household registration is. Mao got the warning from her mother and then called the police officer, politely cooperating with him, she said, because she knew the unexpected visit was just part of his job.

But then Mao was pestered a second time. In October, after she half-jokingly wrote on WeChat that the protesters should “blow up the family compound” of the Yunnan provincial government, the same officer called her—and again at night, this time when she was driving home after working overtime. The officer tried to persuade her to forget about the Fanya case. “The sun is new every day,” he said.

She answered, “If the issue cannot be solved, don’t ever ask me to shut up.” Afterwards she pulled over and cried.

The police don’t care about her case at all, Mao said, but only want to keep trouble out of their jurisdiction. “How can I let bygones be bygones?” she asked. “I can’t accept it if I can’t get my money back… I’ll remember it my entire life.”

Tian Jing, a 33-year-old investor from Shanghai, became WeChat friends with Mao after realizing they shared the same problem. On the eve of a planned protest in Beijing in June 2016, a police officer called Tian to convince her not to attend. He told her to “believe in the country, believe in the government, and believe in the party,” and advised her to let other investors protest for her.

“You’re so ridiculous!” Tian scoffed. The officer argued that she should at least think about her kids, who might want to be civil servants in the future. Tian laughed at the idea, saying she would never let that happen.

The next month another police officer called Tian’s parents, to whom she had never mentioned the Fanya case, to enlist their help in dissuading her from protests. Tian had hid her weekend protesting activities from her parents, saying she had work to do in the office. Later she realized they had already known about her secrets, thanks to police calls. “They were worried that I couldn’t get back home every time,” she said.

Tian called the police back. “If you dare to cause any more trouble, I’ll jump off my building,” she said. “Then my parents will find you.” That ended the pestering.

“Stability maintenance”

Police going after Fanya investors are ordered to fulfill their duty of “stability maintenance” without even knowing—or caring about—what exactly these investors have said online. One investor said that a police officer took a video of his home simply because he needed to prove to his superior that he had completed the assignment.

Such precaution is so extreme among police that officers often run after shadows—especially ahead of big events. In February 2016, Yan Hongfei, a 40-year-old investment banker from Shanghai, reposted a news report about an upcoming G20 finance chief meeting in Shanghai in a WeChat group, without making any comments. The next day the police found him outside his office building to interrogate him. “Do you want to make any trouble?” they asked.

Similar things happened to more investors during last September’s G20 summit. Lin Yaozu, a 50-year-old small business owner in the host city of Hangzhou, said he was summoned by police to sign a letter to guarantee that he would never post online any “instigating” messages about protests during the event.

Eventually, Lin took his 14-year-old son for a trip to the western city of Xian, at the encouragement of local authorities who wanted to empty the city of potential troublemakers before welcoming global leaders. But when they came back, Lin and his son were forced to stay at the Hangzhou railway station for two hours, until two police officers from his neighborhood escorted them home, making sure they didn’t veer off course.

Tian, the Shanghai investor, said she had noticed a suspected plainclothes police officer standing outside her apartment building during the G20 summit. She didn’t speak to him but learned from property guards that he’d asked them a couple of times when she came back home. At least two other investors based in Shanghai and Hangzhou were also monitored near their homes by uniformed or plainclothes officers during the G20 meeting, Tian learned from their chat groups.

To get around the government surveillance, many Fanya investors have learned to communicate via WhatsApp and to use Twitter to spread news of their plight. (Twitter and other Western platforms are blocked in China but can be accessed via virtual private networks, though Chinese authorities are now cracking down more on those.)

A loss of faith

Whether Fanya investors like it or not, their lives have been completely changed by the fraud and what followed.

During the recent Lunar New Year holiday, Zhang Zhengtao, a 33-year-old visually impaired masseur, was grilled by his parents about the Fanya case after traveling from Shanghai to his home village in the central Henan province. Just like in previous years, they kept asking him when he could recover his investment of 150,000 yuan. “That’s not a thing that I can decide,” Zhang replied.

Zhang put his life savings into Fanya at the recommendation of a frequent customer, who was also an agent selling Fanya’s products. He talked Zhang into the investment, citing all the official endorsements including the government document approving Fanya’s setup. “Who else can you believe if you don’t believe the government?” he asked. Zhang thought it was a good point.

Because Zhang can’t see clearly to place orders himself on Fanya’s online trading platform, he handed his account password to the agent to make deals for him. After Fanya went sour, he couldn’t get in touch with the agent anymore. He said he originally planned to use the money to buy a house in his home village and get eye surgery to cure his blindness “when the technology becomes more mature.” But now that he can’t accomplish those two things, he said, it’s difficult for him to even find a girlfriend.

Tian, the Shanghai investor, said that her husband divorced her because over 90% of their investment in Fanya—5 million yuan—came from him. Tian used to travel abroad two or three times a year and buy a luxury handbag every few months—things she can no longer afford to do.

After Fanya was revealed as a fraud, Tian said she hasn’t “slept a good sleep or lived a happy day.” Her friends used to call her ”bouncy,” but now describe her as “quiet” instead.

“I’m speechless about the hooligan government,” said Xu Zhaodi, 67, a retiree from Shanghai. “There are so many fraudsters, and so many corrupt local officials—the government is beyond saving.”

Xu, who had no investment experience before Fanya, sunk her life savings of about 3 million yuan into the exchange, as she was convinced by the official endorsement and the recommendation of her son-in-law’s friend, head of a local bank branch selling Fanya’s products.

Xu said she had “truly loved” the Communist Party after becoming a member as a teenager, but has since lost her faith in it. She would have already quit the party if her daughter, a 30-year-old civil servant with a promising career, hadn’t begged her not to.

Xu had promised to buy her parents-in-law an apartment in the same real-estate complex where she lives. But now she has to hide the truth from them for fear that they can’t take it. Whenever they ask about the property purchase, Xu has to say, “Let’s wait, the housing price is rising.” She said she has to keep lying to them as long as she can, “maybe until their death.”

But even death is a problem. The duo in their 90s contributed all of their pension funds to Xu’s Fanya investment, she said—money that was originally planned to cover the cost of their own funerals. “Now we can’t even afford to buy a tomb,” Xu sighed, noting that a tomb in Shanghai’s suburbs costs as much as 50,000 yuan.

The last hope

The long-awaited trial of 20 Fanya executives is perhaps the last hope for Fanya investors—but it is not comforting by any means. For one thing, the public prosecution only goes after the exchange itself, but not the state banks that recommended its products, and not the government officials who backed its setup.

Investors are also concerned about the “illegal fundraising” charge against the Fanya executives. Under this charge, they are responsible for their own losses from participating in the exchange, according to Chinese laws. That means they are not guaranteed to recover their funds even if the Fanya executives are found guilty.

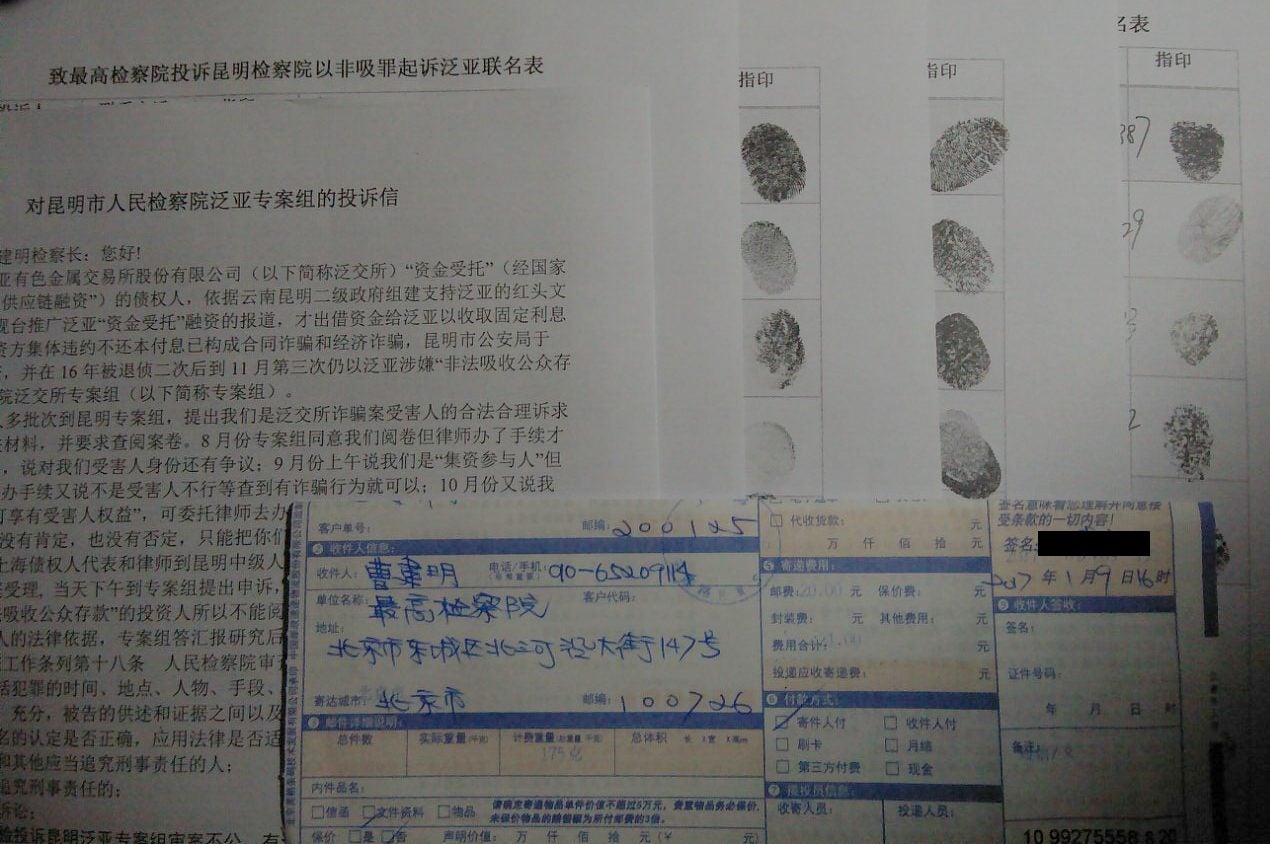

With that in mind, investors are demanding that the Kunming procurator present the case before court with more severe fraud charges, including “contract fraud,” which would recognize their status as victims in the criminal case. That would also give them the right to appoint lawyers to read the file on their behalf, and testify in court.

Investor representatives and their lawyers have presented their demands to the Kunming procurator in charge of the case during recent visits, said one Nanjing-based lawyer who represents Fanya investors and asked not to be named. But the procurator has rejected their demands, citing vague procedural issues. The procurator said that only 20% of the funds Fanya received from investors have been recovered so far, the lawyer added.

When contacted by Quartz, an officer at the Kunming procurator refused to talk about the Fanya case, saying the agency only accepts interviews with journalists licensed by the state.

Previously the investors filed a lawsuit against the Kunming government to the local court, but that was rejected. Now they’re bringing the case to higher-level courts, the lawyer said, although it’s unlikely to be accepted there either.

The investors also plan to file a separate lawsuit against the state banks linked to Fanya—but only after the trial of the Fanya executives is concluded, as a civil suit can only begin after the criminal suit in the same case, according to Chinese laws.

More than 400 investors have crowdfunded 100,000 yuan among themselves to hire lawyers to provide them with legal advice, and represent them in the case if possible. It took them almost a year to find two lawyers (the Nanjing-based lawyer included) who were willing to help them, said a Shanghai-based investor in the group, as most Chinese lawyers don’t want to “take on the government.”

In their latest move, Fanya investors presented their legal demands to China’s top procurator Cao Jianming, in the form of an open letter (link in Chinese) with 300 people’s signatures and fingerprints. They delivered the letter to Cao by courier on Jan. 9, and subsequently posted it on several social platforms including WeChat, Weibo, and Twitter.

Like petitioners seeking the emperor in imperial China, Fanya investors have pinned their hopes on president Xi Jinping. At the end of their letter, they asked the top procurator to bring justice in the Fanya case, citing Xi’s speech on building an uncorrupt judicial system. Only in this way, they wrote, could it “make the Communist Party’s sunshine illuminate the great land of China again.”

In the following week, Meng Jianzhu, China’s top security czar, said during a Bejing meeting (link in Chinese) that law enforcement agencies should quicken their pace in dealing with illegal fundraising cases, including Fanya, to “actively respond to investors’ concerns.” Meng’s speech broke the long official silence on the Fanya case since the Kunming police’s August 2016 statement. Investors felt their efforts had paid off, at least to some extent.

And they are keeping up the fight. Last week, dozens of them in a WeChat group began calling for another protest in Beijing, ahead of the nation’s top two annual political meetings in March. “Let’s unite as one. We’ll definitely win,” one initiator wrote.

Some wrote “Go” to support him. Hopeless ones remained in silence.

Qian Xiaohong, Tan Yaoming, Wang Yue, Mao Lina, Tian Jing, and Xu Zhaodi are pseudonyms used at the request of the interviewees, who fear government retaliation.