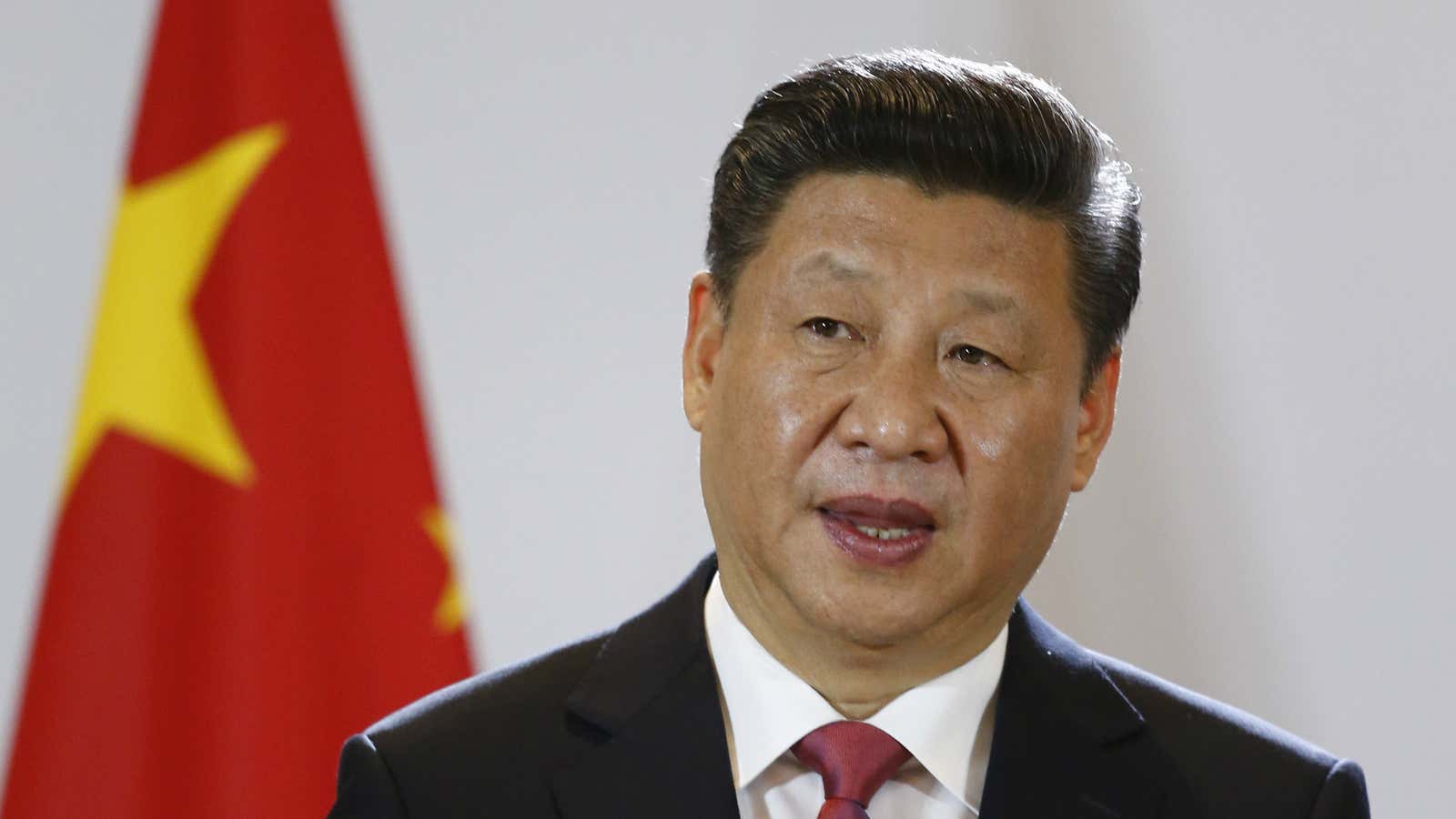

Globalization officially has a new champion. At the World Economic Forum this week, Xi Jinping praised international trade and decried protectionism (and, indirectly, Donald Trump). Does this signal the dawn of a new China-led era of globalization?

Probably not. During the last era of globalization—which, with Trump’s election, seems to be fading—America supported its trade partners by opening its massive consumer market up to their imports. China’s style of international trade, however, hurts rather than helps many of its trade partners.

One easy way to detect this is through the current account balance, the excess of what a country saves over what it spends domestically—or, to put it a little differently, the excess of goods and services that it produces over what it consumes and invests. China’s current account surplus totaled $330 billion in 2015—more than what the entire South African economy produced that year.

This might suggest China is managing its economic growth prudently. That’s not what’s really happening, though.

China has powered its insanely fast growth with a big assist from exports, rather than domestic consumption. In fact, it suppressed its domestic consumption through policies that shifted income from workers to companies, and left China buying fewer foreign goods than it otherwise would. The trade gap that results is the main cause of that large current account surplus. Because China is enormous—accounting for around 16% of global GDP, adjusted for purchasing power parity—when it curbs its own potential consumption, it also snuffs out a decent share of global demand. Weaker demand means less growth for everyone—not something that will endear you to your global trading partners.

It gets worse, though. Any country that persistently produces more than it consumes forces other countries to balance it out, as economist Jared Bernstein explained a while back. That adjustment means those trade partners’ savings rates must fall so that they consume more than they produce. So either their domestic output drops—putting workers out of jobs—or they must borrow to pay for their excess consumption.

The US bore the brunt of China’s policies over the last two decades, thanks to the dollar’s status as the de facto global reserve currency. China’s policies contributed to the buildup of debt in the US housing bubble that triggered the 2008 global financial crisis, as well as to the mass manufacturing layoffs that gave rise to Trump.

The Chinese government is no longer keeping its currency artificially cheap, one of the chief ways it suppressed domestic consumption over the years. Unsurprisingly, its trade surplus—which accounts for most of the current account surplus—shrank slightly this year. However, it still adds up to a hefty 4.5% of China’s GDP, based on projections by Capital Economics, a research group.

At roughly 2% of its GDP, China’s trade surplus with the US makes up a good chunk of its export excess. But if Trump, as promised, slaps import duties on Chinese goods, that imbalance doesn’t necessarily go away.

Instead, the Chinese government will have to accept mass layoffs or add to its already dangerously mammoth debt burden, as we recently explored in more detail. Or it must find other countries on which to foist its surplus production, forcing these trade partners to consume more than they produce. And that’s a style of globalization unlikely to win Xi many popularity contests.