Galal Yousif sat hunched in a quiet studio at the Kuona art center west of Nairobi, his fingers moving deftly over a new sketchbook.

The work in progress comprised elongated human faces crowded in tight formation, their fierce eyes searching the horizon. The drawing depicted a story of unease, especially by the way some of the profiles grimaced and furrowed their brows. But if the sketch was sharply incongruous with the tranquility of where it was being drawn, it was only because it reflected the reality of millions of people from Galal’s home country: Sudan.

What began as spontaneous protests last December due to sluggish economic growth turned into a massive peaceful uprising that ended with the removal in April of one of Africa’s longest-serving dictators, Omar al-Bashir. Yet the transition to a more inclusive, civilian-led rule in Sudan has been tumultuous: bedeviled by internet shutdowns, general strikes, and an attack by security officers on a peaceful protest sit-in that saw 100 people killed, 700 injured, and more than 70 raped.

The state of irresolution and uncertainty continues after Khartoum announced late Thursday (July 11) that it foiled a coup attempt just days after the military junta and civilian protestors agreed to end a political impasse.

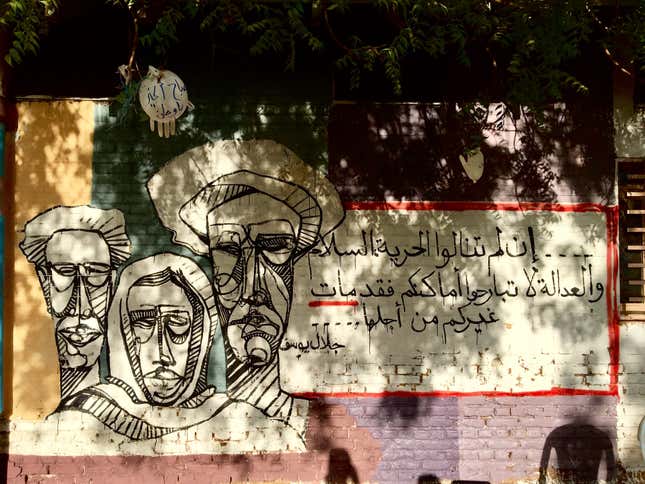

One upshot of the uprising though has been the geyser of colorful and vibrant artwork that has dominated both the streets and Sudanese social media. As thousands kept up a vigil in the capital to ensure a return to civilian rule, artists, long suppressed under Bashir’s rule, turned their verve to the wall and roads.

Since then, murals, paintings, and graphic art have sprung across the nation: agitating peace, extolling the place of demonstrators and martyrs, exhorting the world to stand up for the Sudanese people, and imagining a better future. Besides painting, free books were distributed at the protest sites in Khartoum, drawing tents set up for children, and music concerts held that drew tens of thousands of people.

One of the painters central to this artistic resurgence is Galal, who says art wasn’t just an appendage of the uprising but was at the heart of it. The color from the paintings, he argues, created not just energy among people but also boosted the inspiration for change. Since December, he has produced several murals depicting protestors “screaming” for change and one paying homage to the women raped during the June 3 crackdown.

“The art did a big thing for the revolution,” Galal notes. “We painted on the walls and the ground but we touched the hearts.”

Visual resistance

Artistic expression—be it poetry, music, or paintings—has for decades held an important spot among Sudanese society. Singers like Mohammed Wardi intertwined words from poets like Mohammed al-Makki Ibrahim, Salah Ahmed Ibrahim, and Mohamed Miftah to create melodies of patriotism—particularly during the crucial 1964 and 1985 uprisings.

Sudan’s soundscapes have also held a central position in Africa, especially along the “Sudanic Belt” that stretched from Djibouti and Somalia in the east through to Mauritania in the west. Painters like Ibrahim El-Salahi, the first African artist to get a Tate Modern retrospective, also appealed to the Pan-African, especially with his 1963 masterpiece Funeral and the Crescent that celebrated the assassinated Congolese leader Patrice Lumumba.

Yet a tapestry of sociopolitical misfortunes, economic embargoes, censorship, along with stringent religious edicts under Bashir shattered creative expression, leaving many artists jailed, banned, or exiled.

While the current movement to renew the place of art is revanchist in nature, it also harks back to the modernist art of The Khartoum School that developed in post-independence Sudan in 1960. By using visual art in activism, younger generations are continuing “that memory and legacy of standing up against totalitarian governments and military regimes,” says art historian and the director of the Institute of Comparative Modernities at Cornell University, Salah Hassan.

During Bashir’s three-decade rule, young artists had to run the gauntlet of a state seeking to undermine their potential. Artist Alaa Satir trained as an architect at the university but always looked to art as the ultimate means of questioning authority. Yet a lot of people in Sudan, she says, came to know they are artists by “accident,” and not by being told by mentors and parents or taught in school.

Her work initially centered on the social problems and barriers women in Sudanese society face on a daily basis. But when the anti-government protests began, her artwork took on a political standpoint, documenting the central role women played in shaping the movement. Her series “We are the revolution” honors the centrality of female protestors in uplifting and sustaining the resistance.

Going out into the streets and painting was a “way to heal and to break all the fear that we carried with us, a way to document what’s happening, a way to remind whoever is coming next what we were fighting for.”

Uncertain future

Beyond finding a new visual vocabulary to reflect the new Sudan, artists will also have to overcome many challenges. While the internet has been restored and a power-sharing deal reached, artists like Galal say they have been threatened and their murals painted over by the Transitional Military Council. Alaa also says the education system will have to integrate art into classrooms so that young people will stop viewing it as a hobby or side hustle.

Art critic Salah hopes the revolution will spark new forms of expression that could help Sudan build—to paraphrase American poet Langston Hughes—the “temples for tomorrow.” And the “role of the state should be to support that creativity, to find ways of enabling it but not interfering with it and not to draw a manifesto.”

Galal aims to go back to Khartoum soon and make art that will get his compatriots to think about the future. “People are more united than before,” he said. But the revolution, he believes, shouldn’t end with getting a civilian government. “The revolution for me is a lifestyle.”

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox