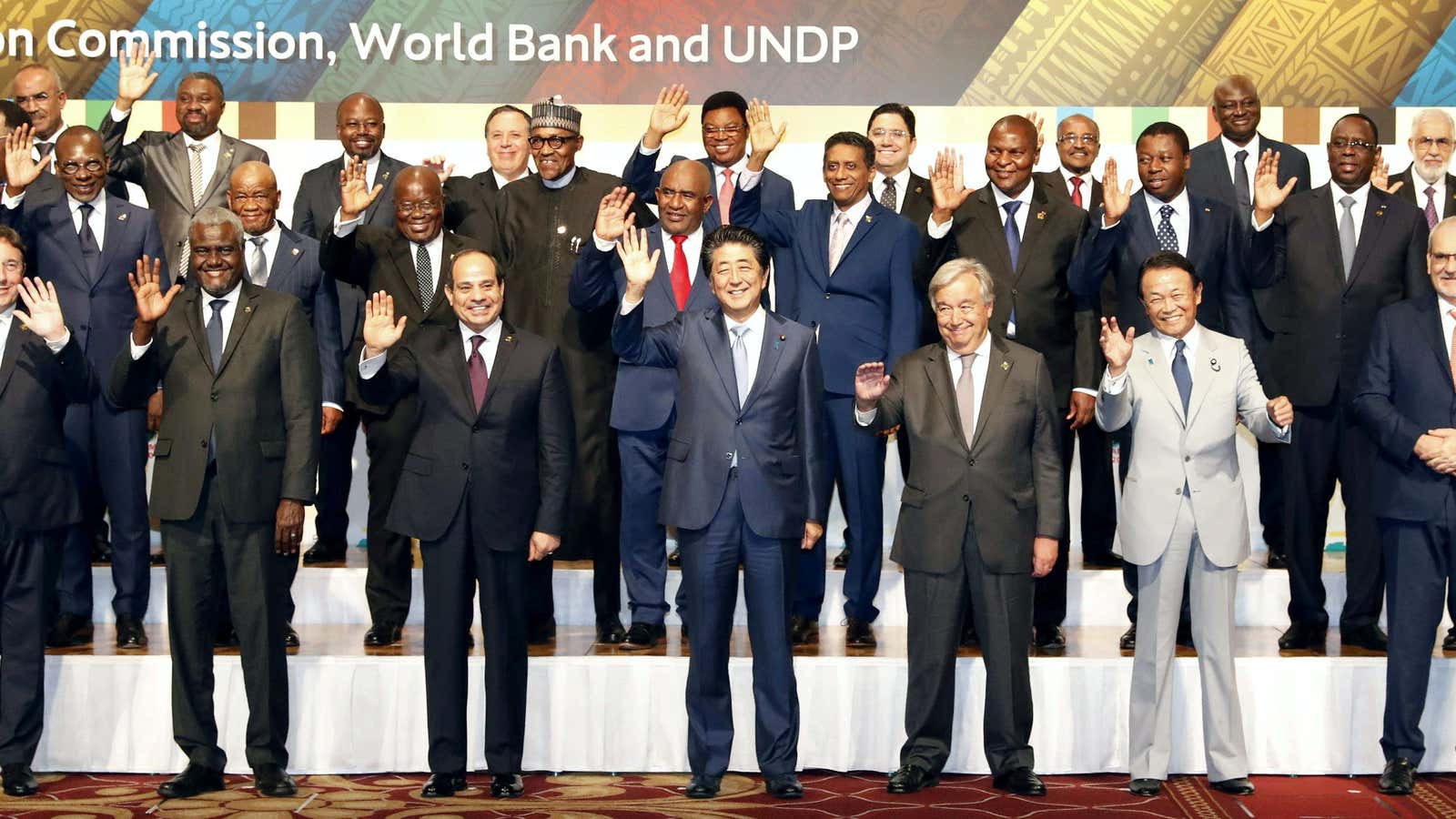

Dozens of African leaders trooped into Yokohama city on Japan’s Pacific coast in late August and heard prime minister Shinzo Abe promise that Japan’s private sector will invest $20 billion over three years in Africa. What’s more, said Abe, Tokyo would offer “limitless support” for investment, innovation, enterprise, and entrepreneurship, with backing from Japan’s government-backed institutions.

The promises of cooperation were made at the seventh Tokyo International Conference for African Development (TICAD). It is one of several such gatherings that now occur across the globe, where countries make their vows to Africa and court African partners for aid, trade, investment. China’s deepening presence in Africa, however, looms large over them all and so it was at TICAD. China is now Africa’s largest trade partner and its largest infrastructure funder. Last year, president Xi Jinping pledged $60 billion for development projects in Africa.

But if Beijing is financing large, visible schemes, Tokyo is focusing on its core strengths by funding partnerships aimed at boosting technological innovation, industrialization, impact investment, institutional building, and climate change adaptation. Tokyo’s strategy is also aimed at providing an ideological counterweight to Beijing by building, as Abe declared at the sixth TICAD in Nairobi in 2016, a partnership “that values freedom, the rule of law, and the market economy, free from force or coercion.”

“It’s a move away from traditional aid towards more commercial engagement, and with it a stronger emphasis on African agency and development agendas over a more traditional prescriptive approach,” says Cobus van Staden a senior China-Africa researcher at South African Institute of International Affairs. At this year’s TICAD, he adds, Japanese officials seemed keen to play down the narrative that they were taking on China in Africa.

But Beijing, van Staden argues, played a large role in proving to external actors that it is possible to have successful commercial engagement with Africa. Given Africa’s growing population, its speedy adoption of technology and improvements in infrastructure and education, there’s a growing realization that the continent could be the next century’s economic powerhouse.

Increasingly, Japan has encouraged its companies to work with African startups and even facilitated potential partnership meetings. Japanese companies, much like their Chinese counterparts, have also looked to Africa as an investment destination.

Last year, carmaker Toyota invested $2 million in Kenyan logistics firm Sendy while Sumitomo Corporation invested in the Nairobi-headquartered pay-as-you-go solar firm M-Kopa. Japanese insurance firm Sompo Holdings financed payment platform BitPesa, while Nigerian motorcycle app Max raised $7 million from Japanese motorcycle manufacturer Yamaha. In late August, automaker Mitsubishi also announced $50 million to enable the Africa-focused off-grid solar firm BBOXX to expand into Asia.

These investments, along with the promises made at TICAD to boost small and medium enterprises, are vital, says George Gachara, managing partner at the Nairobi-based HEVA Fund. “If you want to have a broad-based change in the continent, you cannot ignore the contribution of the private sector,” Gachara said on the phone from Yokohama. The continent, he added, needed to harness Japan’s research and knowledge capabilities to close the digital divide and prepare for a future where mechanization and big data will disrupt employment.

At the Yokohama meeting, Abe didn’t make any major announcements on aid. Cobus says this reflects concerns about the strength of the global economy and may be an indication that the appetite for large loans is waning. This is especially true as China faces criticism that its lending practices are pushing African countries into debt. Van Staden says, “Japan is promoting private sector investment instead, but it remains to be seen how impactful that will be.”