Weekend Brief: Taking it to the banks

Why the failures of Signature and Silicon Valley Bank, and the swelling deposits at Bank of America and Citi, are bad for the planet

Hi Quartz Africa Weekly readers!

We miss you, so for the next four weeks, we’re sending you our Weekend Brief—normally a members-only product—for free! If you like it, we’d love to offer you 60% off a membership. If you don’t, send us your feedback! We read every email.

This past week, even as banks were failing or flailing, climate protestors gathered outside the offices of major banks across the US, cutting up their credit cards and chaining themselves together, exhorting them to stop financing fossil fuel projects.

On the face of it, these protests might seem to be disconnected to the collapses of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank. But as faith in midsize or regional banks falters, depositors will increasingly sock their money away in a Bank of America or a Wells Fargo, the kinds of titanic institutions that the US government could never afford to let fail. Indeed, this started happening almost as soon as Silicon Valley Bank went belly up—Bank of America received nearly $15 billion in new deposits in five days.

The four biggest US banks—Citi, Wells Fargo, Bank of America, and JPMorgan Chase—already hold nearly 50% of all US deposits. As they grab even more of the market, it will become harder and harder for the public to exert pressure on them to, for instance, deny financing to a new oil drilling enterprise in Alaska.

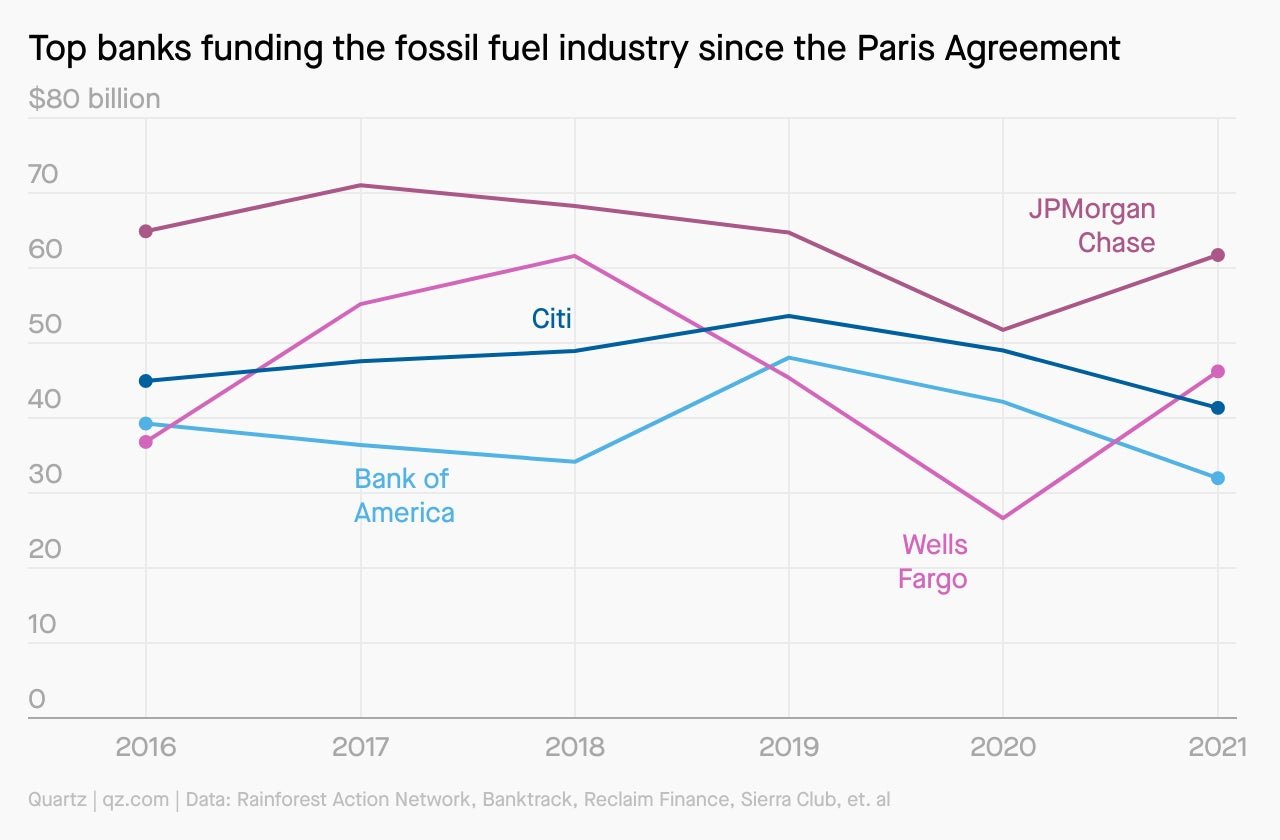

These four banks directed more than $1 trillion in funds to oil and gas between 2016 and 2021, according to data from the Rainforest Action Network (pdf) and other groups. By continuing to fund fossil fuel projects, the climate activist Bill McKibben wrote recently, these banks “are financing the single most dangerous experiment in the history of our species. Cash in those banks equals carbon in the air.”

There is a flip side to the outsized influence these banks wield—and McKibben and others know it. If they were to decide that they’d halt all financing of new gas and oil fields, it would spell the end of fossil fuel expansion. The industry is heavily dependent on capital. Consider, for instance, that the top six oil companies made a combined $219 billion in profits last year—an obscene amount, to be sure, but still much less than the $400 million that the Norwegian oil giant Aker estimates as the cost to explore and drill 13 wells. Only banks can provide that scale of funding, which means they must be persuaded to turn their spigots off.

THE LOAN RANGERS

ONE BIG NUMBER

$214 billion: The projected expenditure on offshore oil projects in 2023 and 2024 combined, accounting for 68% of all spending on newly sanctioned projects, according to Rystad Energy. Aramco alone (pdf) is expected to lay out $55 billion in 2023, and Norwegian firms will spend $21.4 billion the same year.

How does your company prioritize its remote workers? Nominate your company today and see if it will make the ranking in Quartz’s Best Companies for Remote Workers 2023. GitLab, Andela, and ClickUp are among the 83 companies that made it to the list last year. The last date for submissions is April 14, 2023. Nominate your company here.

DAMNED IF YOU DO...

Last December, HSBC announced that it would stop financing new oil and gas. As Europe’s biggest bank, it had been lending an annual $20 billion to fossil fuel projects, making up around 2.7% of all global loans to the sector. It was a win for the climate change movement, but in the US, HSBC has run into repercussions. This past week, Texas added HSBC to its blacklist of companies that are moving away from the fossil fuel industry. Under a 2021 law, state government entities such as pension funds must now divest all publicly traded HSBC securities within a year.

ONE 📠 THING

If, as a senior citizen, you couldn’t attend the protests against banks in person, Third Act, a climate nonprofit that engages people over 60, had an age-appropriate solution for you. Jam up the fax machines of bank CEOs with thousands of letters, Third Act suggested. It was news to us that these CEOs still use faxes, but Third Act seemed to have done its homework. You didn’t even have to go out and find a fax machine in a FedEx print center. You signed your name to a letter on Third Act’s website, and they faxed it in for you. It was like a modern distributed denial of service (DDOS) attack on a website—but retrofitted with a vibe from the 1990s. That’s some hard targeting of the boomer demographic.

QUARTZ STORIES TO SPARK CONVERSATION

- Can mushroom leather become mainstream fashion?

- The temptation of high oil prices is shaking Norway’s climate commitments

- As fake photos of Trump’s “arrest” went viral, Trump shared an AI-generated photo too

- The world’s top climate negotiators can’t end a meeting on time—and it’s hurting their inclusivity

- Jack Dorsey’s fintech company Block is being accused of facilitating criminal activity

- A cash crunch and an expensive dollar are squeezing Unilever out of Nigeria

- Want to cut global emissions by 10%? Stop fossil-fuel subsidies

5 GREAT STORIES FROM ELSEWHERE

📱 Chew’s crew. Shou Zi Chew, the CEO of TikTok, was questioned by US lawmakers this week over security and privacy concerns in what commentators have called a disastrous showing for the company. But Wall Street opinions aside, Chew has the internet smitten. TikTokers have come out in force on the platform supporting the Singaporean native and even drawing Pedro Pascal comparisons. Insider takes a look at Chew’s growing cult of personality online.

♻️ Fauxcycling. Several countries now mandate that companies use a certain level of recycled plastic in their products, but that doesn’t mean materials labeled as “recycled” are actually meeting the mark. In fact, some plastic products that claim to be recycled may not contain even a smidge of the material. Undark points out the glaring loopholes in the “mass balance” system, the current method used to measure and certify post-consumer recycled plastics.

🌀 Amazed. Some people like to unwind on vacation, but Ingrid Rojas Contreras opted to wind her way through various mazes in Europe. Contreras, a Colombian writer, explains that, ever since a 2007 accident triggered temporary amnesia, she has developed a fascination with confusion. Her essay in the New York Times takes readers through labyrinths in Chenonceaux, Paris, and Barcelona, while musing on the delights of being lost.

💰 Having a say. Under a commonly established social contract, citizens pay taxes, and the government decides what to do with the money. But when it comes to public spending, there’s an alternative model of decision-making that could be more democratic and inclusive. A story from the New Yorker looks at the practice of participatory budgeting in Cascais, Portugal, where citizens vote on what policies to fund.

💍 I don’t. Child marriage is legal in all but seven US states. Activists are trying to pass bans nationwide, but it’s proving a difficult campaign. Some conservative states, like West Virginia, have shot down bills on religious or historical grounds, while other state lawmakers are simply unaware that child marriage is an issue. The Washington Post explores the debate around banning the practice in the US, and profiles some of its surprising opponents.

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or topics you want to know more about.

Have a clean, green weekend,

— Samanth Subramanian, global news editor

Additional contributions by Julia Malleck and Clarisa Diaz