Running the world from Davos

Does the Elon Musk give the World Economic Forum too much credit?

Greetings from Switzerland, Quartz members!

At the end of another annual meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos, we ask: Which is the appropriate critique? Is it that the WEF is an ineffective, do-nothing “talking shop” for rich people who can’t stop admiring problems long enough to actually solve them? A “corrupt circle-jerk,” as Jill Abramson, the former New York Times editor, described it for Semafor this week? Or is the WEF becoming “an unelected world government that the people never asked for and don’t want,” as Elon Musk tweeted this week?

After a week at Davos, we have an answer for you: Musk gives the forum too much credit. The WEF does wield power, insofar as it compels thousands of people (roughly 600 CEOs and 47 heads of state among the 2,700 registrants this year) to trek to an out-of-the-way Alpine ski town, where temperatures this week dipped to 2°F (-16°C). But there is no cabal that we’ve ever observed in our years of covering the proceedings—including years when George Soros held court here—and no evidence that WEF wants to substitute for governments. (Surely it would rather woo them to Davos; the organization had to swallow much criticism this year for not even being as successful at that as in years past.)

The forum also occasionally accomplishes things. One example: the 1988 Davos Declaration, which tempered relations between Turkey and Greece. Another: the creation at WEF in 2017 of the Global Battery Alliance, a now-independent public-private partnership (Tesla is among its supporters) to bring more sustainable practices to the manufacture of EV batteries. It’s telling, though, that there aren’t many examples of this kind, at least in the public domain; corporate deals are another story.

If the conspiracy theorists visited the crowded promenade that runs through town, they’d find that most people who come to Davos for WEF, and pay handsomely for the privilege, seem to do so to meet customers, make connections, pitch ideas, and bask in the inevitable self-importance that comes with being in a place where meetings are called “bi-lats” and where proximity to power is mostly measured by whether you got let into the annual Salesforce party (we did not). One principal at a leading consulting firm, chatting over lunch, told Quartz about a schedule rammed with meetings: “I don’t think I could get this much done in three days anywhere else.”

In other words, the WEF is a conference, albeit one with airport-style security, criminally sparse food options, and a dress code that deems snow boots acceptable indoor attire. Just as with other conferences, the same attendees show up every year to hobnob, and speakers say things that don’t match their actions. So Abramson’s “circle jerk” critique isn’t unwarranted. But it isn’t the entire story. In a politically polarized and increasingly precarious world, having places for dialogue—even among overprivileged people—remains a necessity.

THE VIEW FROM THE MOUNTAIN

If anyone was waiting for clear signals about the economy from the brigades of policymakers and wonks at WEF, they were likely to be disappointed. It was all judicious hedging: “on the one hand,” “on the other.” On the one hand, the European winter was not as brutal as expected, inflation was slowing down, and China had reopened. On the other hand, central banks are still pushing interest rates up, and China’s reopening is likely to lift oil and gas prices. “It is less bad than we feared a couple of months ago,” Kristalina Georgieva, the IMF’s managing director, said on the final day of WEF. “But less bad doesn’t mean good.” So much for that.

In private conversations, though, corporate executives were unequivocally cheerier. They weren’t seeing any great slackening in their business, or in consumer spending, and unemployment numbers remained low. (The rash of tech layoffs, some of which were announced during the WEF week, were ascribed to over-hiring during the pandemic.) The European scenario is somewhat worrying, CEOs admitted—but in the US and China, with governments bent on investment, there is no call for dire gloom.

CRYPTO WINTER INDEED

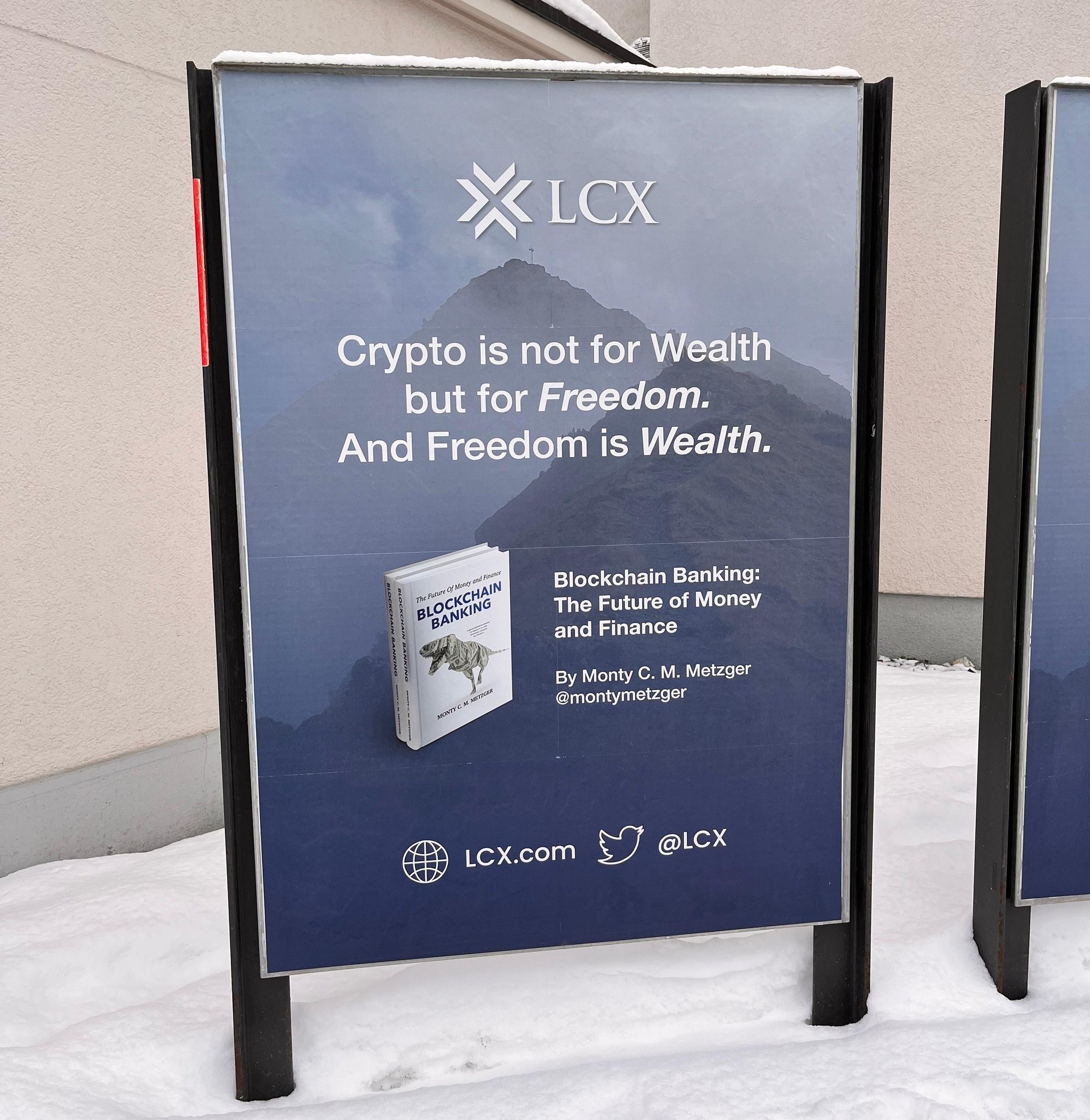

How swift the world turns. Last May, during the WEF, bitcoin’s price hovered around $31,000. The slide had not yet turned into a crash, and crypto entrepreneurs flush with success lined the Davos Promenade with billboards and crypto-hauses. The euphoria formed a strange tonal counterpoint to the shock of the still-new Ukraine war.

This year, the air has gone out of the crypto community. There were still feeble attempts at advertising. But it felt like some kind of capitulation that crypto-bros were now harking back to some abstract libertarian ideals rather than the value of crypto as a store of wealth. Equating crypto with freedom won’t soothe the jangled nerves of investors who lost their shirts in the crash last year.

At the Blockchain Hub, crypto evangelists conceded, in various subdued voices, that the industry needs regulation. “We have to work closely with regulators,” said Changpeng “CZ” Zhao, the CEO of Binance, a company known for dodging regulators. He may have been saying the safe thing—but it was remarkable that he was saying it at all. Anthony Scaramucci, the founder of SkyBridge Capital and erstwhile friend of Sam Bankman-Fried, the disgraced founder of the crypto exchange FTX, went further. “If you want to hurt the industry, don’t regulate it,” Scaramucci said. “Let it stay as the wild west. You’ll close down all trust in it.”

BUZZWORD: GENERATIVE

The phrase “generative AI” sneaked its way into countless conversations in Davos. Some are pinning their hopes to it while others fear its effects on art, education, and the labor market. One vocal cheerleader was Satya Nadella, the CEO of Microsoft, which owns a stake in Open AI, the company that unleashed ChatGPT.

In his annual conversation with Klaus Schwab, WEF’s grand panjandrum, Nadella told a story that is worth reproducing in full. He’d been in India in January, he said, and saw a demo of an Indian farmer accessing a government program via an app:

“He just expressed a complex thought in speech in one of the local languages. That got translated and interpreted by a bot, and a response came back saying ‘Go to a portal, and here’s how you can access the program.’ He said: ‘I’m not going to go to the portal, I want you to do this for me.’ And [the app] completed it. The developer building it had taken GPT and trained it over all of the government of India’s documents and then scaffolded it with this speech recognition software.

“Think about what this meant. A large foundational model developed in the west coast of the US a few months before had made its way to a developer in India, who then added value to it to make a difference in a rural villager’s life. I’ve never seen that type of diffusion. We’re still waiting for the Industrial Revolution to reach large parts of the world, 250 years after. The internet maybe took 30 years. The cloud and mobile took 15 years. Now we’re talking months.”

It all sounded great. But we’ve gotten so used to how the global economy works that we know there must be collateral damage stemming from ChatGPT and AI. Sure enough, the same week, Quartz reported on how Open AI hired underpaid Kenyans to scrub ChatGPT of toxic content and then sacked them. And at Davos, the science-fiction writer Neal Stephenson reminded his audience of creative professionals whose work is used to train AI systems—and who then risk being replaced by those same systems. “A lot of the time,” he said, “it seems like the internet and the web are just a big machine for finding incredibly ingenious ways to screw artists.”

Generative AI will be a game changer, without doubt. But it will still be predominantly wielded for priorities decided by the kinds of people who gathered this week in Davos.

BY THE NUMBERS

40%: The percentage of Davos panelists in 2023 who were women

27.5%: The percentage of Davos attendees in 2023 who were women

2045: The year by which Germany will achieve carbon neutrality, as German chancellor Olaf Scholz told the WEF

2060: The year by which China will achieve carbon neutrality, as declared in Davos by Chinese vice-premier Liu He

25: Number of minutes it takes, on average, to get from downtown Klosters to Davos on the WEF shuttle (aka Quartz’s new favorite venue for meeting people)

12: Number of minutes, on average, it seems to take for WEF’s scanty salads and sandwiches to run out as soon as they emerge in the hall of the Congress Centre every afternoon

ONE 🏔️ THING

A WEF week highlight for many Davos visitors is an after-hours toboggan ride to the bottom of the Schatzalp Funicular. But this week, in a very privileged but personal reminder to delegates about the urgency of the climate crisis, the 2.8-km run was closed due to insufficient snow. Which meant that, after he was grilled on stage at a Politico reception in the Hotel Schatzalp, the only mode of transport available to Uber’s Dara Khosrowshahi was the slow cable car down.

QUARTZ STORIES TO SPARK CONVERSATION

- Sam Bankman-Fried cannot shut up

- Why does Twitter’s For You page feel so chaotic?

- How chamber music can make you a better collaborator, whether you play or not

- Warnings about India’s sinking town have been ignored since 1976

- The FTC may ban non-compete clauses. Here’s what workers think about that

- Amazon’s dominance has limits: Here’s what consumers still buy directly from makers

- Dakar is reclaiming its place as the cultural capital of Africa

5 GREAT STORIES FROM ELSEWHERE

🪸 Still reef us. Coral reefs around the globe are dying, but one ecosystem off the coast of Honduras is bucking the trend. Still, scientists have yet to pinpoint why Tela Bay has avoided the fate of other Caribbean reefs, especially as it’s located in sewage and nitrogen-filled waters. Nautilus dives into the mystery behind the little-known reef, which has raised hopes that these aquatic communities are more resilient than we think.

🚞 Slow way home. This Lunar New Year, China’s transport ministry predicts over two billion journeys will be made across the country. The Economist takes a seat on a so-called “green skin” train, the cheaper, trundling mode of transport in China’s sprawling rail network, and speaks to several migrant workers aboard. Touching upon the passengers’ jobs, finances, and family, the conversations also give a snapshot of the country’s rural-urban divide.

🐟 Tinned is in. Fish from a can is back on the menu. Tinned sardines, the working-class staple, have seen a revival among younger generations as a healthy, convenient ingredient. But it’s more than just omega-3s fueling the trend. As Eater explains, the old-school packaging is a big draw, and with growing concern about sustainability and toxins in seafood, smaller creatures on the food chain are considered better for both the plate and palette.

🧬 Edits for all. CRISPR technology entered the scene over a decade ago, providing the key to editing our own DNA. Now gene therapy may soon enter the mainstream. Just last year, MIT Technology Review reports, base editing was used in a human trial to permanently lower participants’ cholesterol levels. But with revolutionary disease treatment on the horizon, questions of costs and ethics still remain.

❓ BDQs. When forming a question, many of us try to frame it in a clever way, winding it up with a preface and dropping in the right lingo. But asking intelligent questions doesn’t necessarily yield the most helpful answers. In fact, we should probably be asking more “Big Dumb Questions,” argues a piece from the Atlantic, as casting a broad query can often catch unexpected, illuminating responses.

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or topics you want to know more about.

Have a chill weekend,

—Heather Landy, executive editor; Samanth Subramanian, global news editor.

Additional contributions by Julia Malleck