Hi Quartz members!

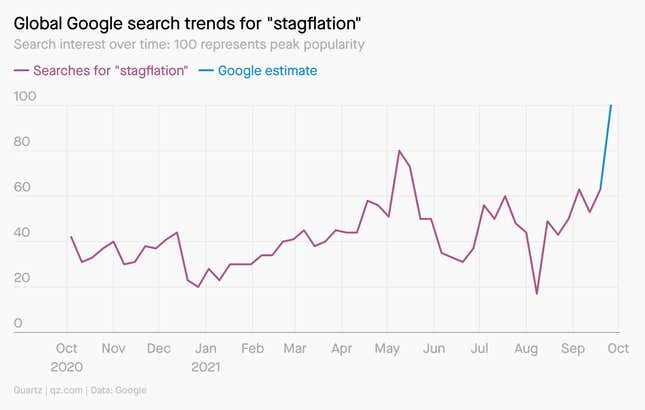

As supply chains heave under rising post-pandemic demand, prices are climbing around the world. The strained links that bind the economy together could even disrupt Christmas, and like small talk about when to order gifts online (it’s too late), conversations about stagflation are officially on the rise.

Stagflation refers to a period when sputtering economic growth and joblessness coincide with rising inflation. The good news? Economic growth is forecast to be 7% in the US next year, the jobless rate is 4.8% and falling, and consumer price inflation in the last 12 months was 5.4%.

When stagflation reared its ugly head in the 1970s, inflation was higher than that for eight straight years, peaking at 14.5% in 1980, when US growth was -0.3% and the unemployment rate finished the year at 7.2%.

Just ask Olivier Blanchard, the former IMF economist, who says “we are not seeing anything like stagnation. What we are seeing instead is very strong growth, fueled by private and public demand, hitting supply constraints, and leading to some sharp price increases.”

That doesn’t mean everything is rosy. The Federal Reserve, while expecting higher inflation, has seen rising prices outpace its forecasts. Laura Rosner-Warburton, an economist at the research firm MacroPolicy Perspectives, warns that wages aren’t rising fast enough to keep up.

The upside is that high prices can cure high prices—if shortages motivate businesses and governments to invest in production, cut red tape, and open up competition, and if the pandemic continues to subside. The real stagflation fear isn’t now, but next year, if central banks, spurred by political and market pressure, tighten monetary policy, which would slow economic growth without necessarily resolving the real drivers of inflation.

That’s, ironically, why the Fed has said it will tolerate higher inflation than the 2% average it usually targets—because it wants businesses to invest in anticipation of higher demand, helping resolve the shortfall of private investment that has plagued the US economy. It’s bad luck for the central bank (and the rest of us) that a pandemic hit in the middle of that experiment.

The backstory

- This isn’t the 1970s. A variety of factors that went into the worst US inflation experience don’t exist today. Government borrowing is set to fall precipitously next year, even if president Joe Biden’s agenda is enacted. Unions have less power and fewer contracts contain inflation accelerators. Interest rates remain low, with markets buying the idea (for now) that rising prices are a temporary phenomenon. And a liberalized energy market should mean fuel shocks pass more quickly.

- Inflation has been too low for a decade. That means the Federal Reserve and European Central Bank have decided they can let price increases run hot for a while. ECB president Christine Lagarde, while calling for patience, recently noted the growing risk of price increases, as inflation in the euro zone hit a 13-year high.

- Bad psychology is a risk. One fear is that inflation expectations become “unanchored,” and people start planning for rising prices, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy. The Fed is confident that markets and consumers will take current inflation in stride, but one of its economists recently questioned whether there’s reason to believe that.

Breakout session

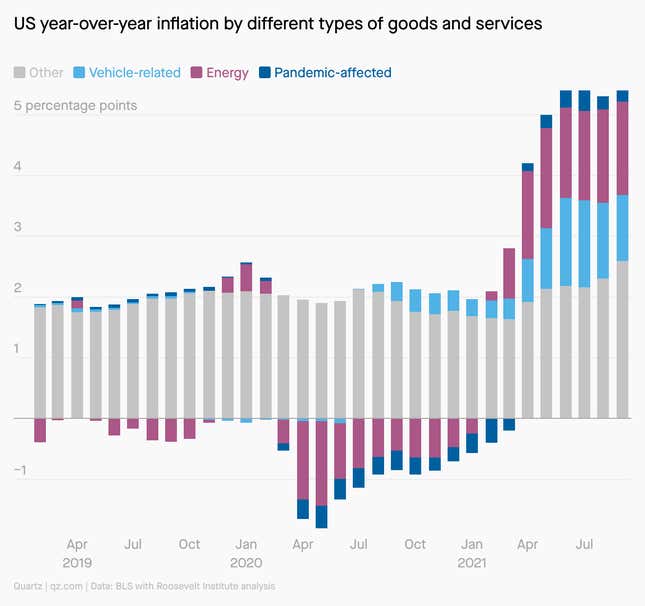

This week’s consumer price index report showed a 5.4% average increase in prices in the 12 months through September, but economists look past the top-line numbers to get a sense of what’s behind the change. In his very first story for Quartz (🎉 ), econ reporter Nate DiCamillo drummed up a chart that helps show which sectors are driving increases:

It suggests the economy is working through pandemic-induced shocks. A shortage of semiconductors that shrank new car supplies boosted used car prices to record-high levels in the summer. Airplane tickets, meanwhile, became more expensive as vaccinated passengers flocked to airports. But prices for both those items have been falling in the past couple of months, reducing their contribution to overall inflation.

What to watch for next

- Taper tantrums. Central banks are likely to slow purchases of financial assets before they hike interest rates, a move known as tapering that famously shook financial markets in 2013. This time, the Fed appears to be foreshadowing a reduction in “quantitative easing,” as the practice is called, toward the end of 2021.

- The “PCE” print. The US central bank’s preferred measure of inflation comes from personal consumption expenditure data collected by the US government, which measures a broader swath of consumption and attempts to account for how consumers substitute cheaper goods for pricier ones. The next release of that data will be Oct. 29.

- The next Fed chair. Fed chair Jay Powell’s term expires early next year; Biden will either renominate him or install someone new. The administration is leaning toward retaining Powell, who has kept the economy on track, but progressive critics say he’s not tough enough on banks or ready enough for climate change.

- Stuff on the move. A lot of our problems would be solved if clogged supply chains clear (and public health restrictions caused by the pandemic continue to loosen). The good news? The worst may be over. The bad news? Normalcy doesn’t return until mid-2022.

- Does the US ban oil exports again? Gas prices are causing political and economic agita in the White House, which is one reason the ostensibly environmentally-friendly president okayed more oil drilling on federal land. There’s even discussion of reimposing the US ban on crude oil exports lifted in 2015, but economists don’t think it will do much to improve prices at the pump.

One 💡 thing

An inflation debate, naturally, created the first consumer price index. In the 1970s, Fed chair Arthur Burns dismissed price increases as temporary aberrational factors; to prove his point, he asked Fed economists to create price indexes that took out the special one-time recurring glitches. So they created the first core CPI, and stripped out food and energy. Except they kept having to take more things out, because more price pressures started showing up elsewhere: in used cars and home ownership and women’s jewelry and mobile homes. Only then did the Fed admit it had an inflation problem, and we’ve been looking at CPI ever since.

Quartz stories to spark conversation

📈 The oldest US commodities index is at an all-time high

🔍 Inside Africa’s biggest cryptocurrency scams

🇨🇳 A popular iOS app was developed by Chinese police

🚀 Is Blue Origin’s culture dysfunctional and dangerous?

✊ A US bank has unionized for the first time in 40 years

💱 Everything you need to know about DeFi

🚪 Why rejection stings so hard for internal job applicants

5 great stories from elsewhere

📊 Don’t call it stagflation. On Substack, Ryan Avent agrees with us: There’s little to be gained from trying to force pandemic economic circumstances into a 1970s narrative.

😶 China’s hit list. On The Scholar’s Stage, Tanner Greer says Beijing’s tech crackdown seems to be targeting industries that use short-term incentives to strip people of their agency.

💬 Behind bars. As a teen, the chairman of Nike’s Jordan brand went to prison for killing someone. After keeping it a secret for decades, Larry Miller tells his story to Sports Illustrated.

🔌 Off, the grid. The Washington Post looks at the future of electric vehicles, and how ill-prepared America’s already-shaky electric grid is to accommodate it.

🤯 Reality just seems rigged. Jon Stokes attributes the modern penchant for conspiracy theories to the way content is presented visually on social media.

Did you like this email?

Help us out! Please take a minute and tell us what you think about Quartz’s member-exclusive emails.

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or topics you want to know more about.

Best wishes for an affordable weekend,

Tim Fernholz, senior reporter (reweighing his consumption basket to emphasize snacks)

Kira Bindrim, executive editor (permanently scared away from buying a car)