Dear readers,

Welcome to Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extra-terrestrial sphere. Please forward widely, and let me know what you think. This week: Relativity’s big raise, a NASA pioneer, and Virgin Galactic’s Italian astronauts.

🌘 🌘 🌘

The big news this week is big money: Relativity Space raised $140 million in a series C round. The rocket-building startup led by Tim Ellis and Jordan Noone—former Blue Origin and SpaceX engineers, respectively—is stocked with veterans of the new space industry.

The pitch is simple: Ellis and Noone saw how their former employers were cutting costs, particularly with 3D-printing, and thought, boy, what if we just printed the whole thing? (Well, 95% of the whole thing.) “Fixed tooling, supply chain, manual labor, all of that stuff is what makes rockets and aerospace so slow and expensive,” Ellis says.

Now, LA-based Relativity has all the essentials of a rocket firm—a test site, a launch pad, and now, enough cash to finish building its rocket and get it to orbit, which they expect to do in 2021.

The company’s extra-large 3D printers have been turning out tanks, structures, turbopumps and complete engines. Ellis tells me that they have now performed more than 200 engine tests, and that the next step for the company will be progressing to integrated testing of the entire two-stage system.

The company isn’t trying to compete directly against SpaceX, ULA and the other big orbital launch companies. It wants to address the pain points of small satellite companies that are often the secondary payload on big launches. Relativity’s Terran 1 rocket aims to carry just over a ton of payload to low-Earth orbit for $10 million; SpaceX’s Falcon 9 can take about 25 tons for $62 million.

SpaceX is cheaper by the pound, but Relativity is betting that companies will pay a little extra to fly on their own schedule or to bespoke orbits. It is a risky business. There are many small-rocket startups, and not all will survive; a promising one, Vector, went belly-up this summer. SpaceX has also shown an interest in getting into the market with ride-share missions tailored to smaller satellite companies.

Relativity expects that its focus on 3D printing will allow it to be more flexible than competitors. The company said this week that it will expand the diameter of the Terran 1’s nose cone to three meters, allowing it carry bigger satellites and compete directly with rockets like Arianespace’s Vega or India’s PSLV.

“Making a bigger payload faring this late in the game effectively would have been impossible with traditional technology,” Ellis says. “You would have had to scrapped the tooling and a lot of the other features that we changed on the rocket to accommodate that.”

Being a proper space company, Relativity has the wild goal of being the first company to print a rocket on Mars. In fact, it could print a lot of things in a lot of places, which is one reason the company has attracted so much investment. Its newest funders include Mary Meeker’s Bond Capital, Tribe Capital, former Hollywood super agent Michael Ovitz and the actor Jared Leto. (Safe to say that space investments have now entered the mainstream of VC land.)

Relativity’s additive manufacturing secret sauce could be attractive to other aerospace companies, or anyone doing precision manufacturing. Relativity, Ellis says, wants to “be the biggest customer of [SpaceX’s] Starship or [Blue Origin’s] New Glenn, [and] build the intelligent factory on Mars.”

By the way, what does he think of Elon Musk’s new rocket?

“It’s big!” he says. “I have to tell you, I’ve done the math on printing Starship. Some interesting results there.”

🛸 🛸 🛸

Imagery interlude

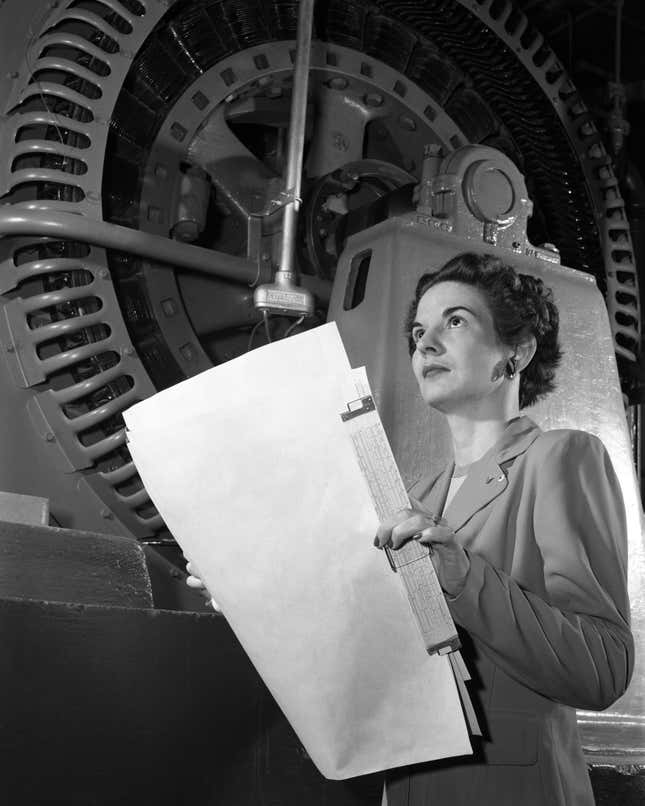

NASA opened for business 61 years ago this week, on Oct. 1, 1958, after president Dwight Eisenhower determined that a new organization was needed to develop space technology in response to Russia’s Sputnik satellite launch. The new organization was built on the existing National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA). Looking for a photo to commemorate the occasion, I instead discovered this great image of Kitty Joyner, the first female NACA engineer (and presumably, among the first female NASA engineers). Joyner was the first woman to graduate from the University of Virginia’s engineering school in 1939 after she took it to court to force it to admit qualified women.

Joyner spent 32 years at NASA’s Langley research center, managing wind tunnels and contributing to investigations of aerodynamics and supersonic flight.

🚀 🚀 🚀

SPACE DEBRIS

Not so NEO. Readers, I regret the hype. When NASA’s Thomas Zurbuchen said last week it would be a good idea to launch an infrared telescope to hunt for near-Earth objects (mostly asteroids) that could crash into the planet, he just meant it would be a good idea. Now, the agency tells me that IF the funding comes together, NASA will consider the mission. Some good news: The US Senate wants to spend some $78 million next year on near-Earth object observations. If that becomes law, it’s likely to to be the first down payment on an actual NEO survey mission, which could cost as much as $600 million.

Virgin Italia. Richard Branson’s space tourism company Virgin Galactic announced that it will fly three Italian Air Force researchers on its rocket plane “as early as 2020.” Galactic is in the process of going public on the stock market and moving to its operational spaceport in New Mexico. It flew its first passenger to space in February 2019. It’s not clear yet when regular service will begin or even when the next flight of the SpaceShipTwo will be attempted, but it makes sense for Galactic to start its program by flying trained military personnel and not, say, Justin Bieber.

IOU ULA. United Launch Alliance, the Lockheed Martin-Boeing joint venture for building rockets, won two contracts this week that epitomize the criticism the JV receives from competitors.

The first goes like this: ULA sold five heavy rockets to the US Air Force for $1 billion, then also receives a launch-services contract for an additional $1.18 billion to actually fly the rockets. The total cost of the five launches averages to $436 million a pop. (SpaceX sold the USAF a similar rocket last year for just $130 million, all-in.)

In the second, the USAF bought three medium rockets from ULA to launch in 2019. Because the missions were delayed, the Air Force is paying an extra $98.5 million to cover launch costs in the next year. The practice of splitting the rocket-building costs and the service costs is often seen as a way to subsidize ULA, which has few customers beyond the US government. The good news is that these are the last sole-source contracts that the Air Force will assign without competition, and the last time it plans to pay separately for vehicles and services. Now, the military just has to pick the contractors…

A good week to be Intuitive. Intuitive Machines, a Houston-based space autonomous systems startup, is on the up and up. First, the company won a long-simmering lawsuit against Moon Express, another startup that had hired IM to work on a lunar lander but didn’t pay for the job. Now, an appeals court decision confirmed that Moon Express should pay IM almost $2 million in cash and $2.25 million in stock as a penalty. The fun didn’t stop there: IM announced that it had tapped SpaceX to launch a lander called Nova C to the moon in 2021, part of NASA’s program to hire private firms to do lunar scientific research.

Starship. Enterprise? On Saturday those of us on the space beat trucked down to Brownsville, Texas, to see Elon Musk give a talk about Starship, next rocket being designed by SpaceX. The big science fiction-looking metal rocket was impressive, and so was the speed with which it was assembled over five months.

Will it will fly to orbit in six months, as Elon forecast? Highly unlikely. And the rocket itself can’t get to orbit usefully without an as-yet-unbuilt booster. But the demo will light a fire underneath anyone else building a heavy-lift rocket (Boeing, Blue Origin) that isn’t publicly showing off test hardware and lighting up engines. That alone may explain the recent friction between Musk and NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine.

Still, I want to know more about how this rocket will make money. The renderings we’ve seen so far are largely focused on the crewed version. The real money will be in launching hardware. And how much will a Starship launch cost?

Your pal,

Tim

This was issue 17 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send your most improbable space investors, badass NASA engineers with slide rules, tips and informed opinions to tim@qz.com.