Dear readers,

Welcome to Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extraterrestrial sphere. Please forward widely, and let me know what you think. This week: NASA and the billionaires, the FCC wants its money back, and Blue Origin’s new deal.

🚀 🚀 🚀

The rocket billionaire discourse, heady as it is, can distract from the facts. Here’s one: NASA saved at least $548 million, and perhaps more, thanks to just one contract with Elon Musk’s SpaceX.

Last week, the US space agency tapped the company’s Falcon Heavy rocket to launch a space probe to one of Jupiter’s moons, Europa, in 2024. The much-awaited Europa Clipper mission will fly by and assess the evidence of water—and extra-terrestrial life—on the astronomical body. The mission was driven through Congress thanks in large part to the support of one former lawmaker, John Culberson, who navigated it through the sea of veto points and competing priorities that often stands between scientific hopes and their realization.

One of the deals made to get this mission off the ground concerned Boeing’s Space Launch System rocket, a huge space vehicle designed to return humans to the moon or Mars. There was just one problem: It emerged as a kludge from the cancelation of another program, and there were no concrete plans for it. A decade ago, the folks behind each project had gotten together and joined forces to justify one another’s work. “Once built, SLS would be a rocket with nowhere to fly,” David W. Brown writes in The Mission, his account of the project. “Europa was a somewhere.”

The delayed SLS has yet to fly. Its first mission is expected around the end of this year. But since the SLS became central to the Trump administration’s Artemis program to return to the moon, NASA auditors have pointed out, in addition to the massive cost, that there would not be enough SLS rockets for both tasks.

In 2019, NASA’s inspector general sounded out the possibilities (pdf), and wasn’t bullish on any of them, particularly on price: Even accounting for the fact that the SLS could get the probe to Jupiter faster (saving money spent on the program back home), the system would cost about $726 million. Two other rockets available for purchase, the United Launch Alliance’s Delta IV and the Falcon Heavy, were forecast to cost $450 million each.

The deal NASA eventually made with SpaceX for the Falcon Heavy, however, will cost just $178 million. Think about that: In just two years, the price of launching a space probe fell by 75%; it’s less than the cost of the rocket that launched the latest Mars rover last year. This will enable NASA to direct more resources to other science programs (as well as getting the SLS off the ground).

“Having that launch capability at that price point just saves so much, particularly for the science part of NASA that just does not have the mega-budgets that human spaceflight does,” says Casey Dreier, a space policy analyst at the Planetary Society. “To see other future missions by NASA able to leverage the lift capability of the Heavy at that price point opens up a significant amount of space access.”

The drop in cost is directly traceable to SpaceX’s approach to designing rockets, and to the partnership NASA struck with Musk’s space firm in its early days.

The Falcon Heavy, which didn’t even exist when the Europa mission was being planned, has only flown three times. But it will launch at least five more times, including for a NASA mission to an asteroid called Psyche, before Europa is expected to get underway in late 2024.

This is a transformative period for the maturing space industry, as billionaire funders and new business models increase the capacity of private actors. The egos involved may take up a lot of oxygen, but the goals of the commercial space business are not mutually exclusive with NASA’s scientific pursuits; quite the opposite, in fact: They’re enabling more science than before.

🌘 🌘 🌘

Imagery interlude

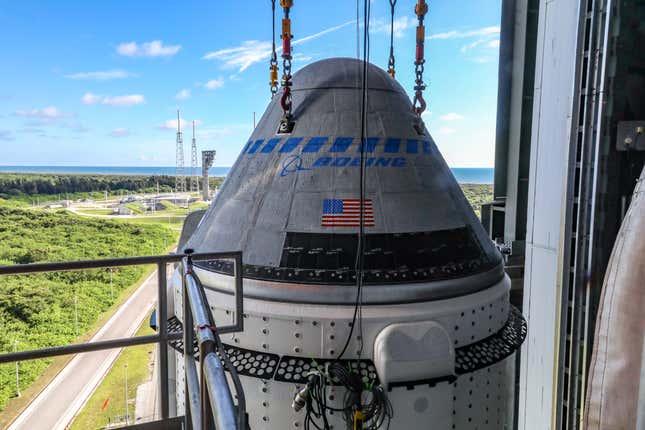

On July 30, NASA and Boeing plan to launch a new, uncrewed test flight of the Starliner spacecraft, if the weather in Florida cooperates. The vehicle is designed to carry astronauts to the International Space Station. Here it is, settling in place on top of its rocket:

Starliner was built as part of the same NASA commercial crew program that hired SpaceX to build the Dragon spacecraft, which now regularly carries astronauts to the orbiting space habitat. The Starliner failed to perform on its first flight test, but after an investigation and another 18 months of work, the vehicle is now expected to demonstrate that it can safely transport humans .

🥇🥇🥇

I’m finding broadcasts of the Olympic games by NBC here in the US to be…subpar. Luckily, my media outlet of choice is producing a newsletter about the games that is helping me keep up with what’s happening, while imparting intriguing facts, like that India has the worst population-to-medals ratio in Olympic history. (It’s working on fixing that.) Join me in the fun and subscribe to our newsletter, Need to Know: Tokyo Olympics.

🛰🛰🛰

Space debris

Re-origin. Blue Origin made more waves this week, with a new offer to NASA in a public letter: We’ll cover $2 billion in costs if you hire us to build a moon lander at the cost of an additional $4 billion or so. Blue was competing to be one of two firms to build a lander for NASA’s Artemis program, but due to limited funds, NASA chose SpaceX alone to do the job. Meanwhile, Blue and the other competitor, Dynetics, have challenged the contract award. It’s not clear if the strategy outlined in the letter is even allowed under NASA contracting rules, but you have to wonder: What might NASA have decided if this new offer was the original pitch? I’ll be writing more about this soon, so send me your thoughts.

Rocky lab. The US-New Zealand space firm Rocket Lab planned to launch a US military satellite early this morning, a return to form after a failed May launch. Ahead of becoming publicly traded later this year, the company also faces allegations of creating a toxic work environment after the New Zealand government ordered the company to pay $67,000 (NZ$97,000) to an engineer who was unfairly dismissed. The complaints about being overworked and underpaid mirror similar stories of burnout at SpaceX and other hard-charging startups.

The FCC would like its money back, please. The US Federal Communications Commission has asked SpaceX and other participants in its program to subsidize rural broadband internet to give back portions of their awards. The recall comes after public complaints that the agency made areas that already have broadband access eligible for subsidies. SpaceX, which received $880 million through the process, is being asked to return subsidies related to about 6% of the geographic areas where it won them. And where’s the next FCC chair, anyway?

Astronaut rights. The who-is-an-astronaut debate spurred by the flights of Richard Branson and Jeff Bezos saw an intervention by US regulators that, well, doesn’t clear anything up all that much but makes it less likely for space tourists to be recognized by the government as astronauts. When it comes to suborbital flight, Quartz will stick to calling passengers space tourists.

German rocketeers. Isar, a German company developing a small rocket, raised $75 million this week. While the marketplace for small launchers is both crowded and, Rocket Lab and Virgin Galactic aside, short on success, the sector is still missing a European champion.

Your pal,

Tim

This was issue 102 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send your thoughts on Blue’s HLS gamble, ideas for the best new FCC chair, tips, and informed opinions to [email protected].