Susan Sontag’s 54-year-old essay on “camp” is essential reading

What do Swan Lake, Tiffany lamps, and “Broccoli” feauring Lil Yachty all have in common? Ostensibly, nothing. But a thread runs through them all: the cultural trope known as “camp.”

What do Swan Lake, Tiffany lamps, and “Broccoli” feauring Lil Yachty all have in common? Ostensibly, nothing. But a thread runs through them all: the cultural trope known as “camp.”

Camp also happens to be the theme of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s much-anticipated costume exhibition, the New York City museum announced this week. “Camp: Notes on Fashion” will be unveiled on May 6 at the annual Met Gala, an event underwritten by Gucci and led by Vogue editor-in-chief and Condé Nast artistic director Anna Wintour. The gala will be co-chaired this year by the singer and actress Lady Gaga, the tennis star Serena Williams, Gucci creative director Alessandro Michele, and singer Harry Styles (who recently posed in a very camp livestock-filled Gucci campaign).

Andrew Bolton, head curator of the Met’s Costume Institute, will explore how the “camp sensibility” can be traced back to the French court under Louis XIV, who gathered the decorated Parisian nobility at Versailles. In that palace of high camp, “everything was pose and performance,” as Hamish Bowles puts it in Vogue. And Bolton told the New York Times that we live now in the midst of another camp explosion: “Whether it’s pop camp, queer camp, high camp or political camp—Trump is a very camp figure—I think it’s very timely.”

The exhibition is inspired and informed largely by Susan Sontag’s brilliant 1964 essay, “Notes on ‘Camp,'” a treatise written over 50 years ago that managed to predict the bizarre features of today’s cultural scene to an uncanny degree.

What is “camp,” anyhow? Let Susan Sontag explain

The essence of Camp is its love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration.

This is probably most-cited definition of Camp in Sontag’s essay, and it is how she introduces her readers to the elusive “Camp sensibility.”

Though in modern usage “camp” is often used as synonymous to “kitschy” or “flamboyant.” Sontag’s definition is far more nuanced. ”Camp is esoteric,” she explains, “something of a private code, a badge of identity even, among small urban cliques… I am strongly drawn to Camp, and almost as strongly offended by it.”

Sontag’s “random examples of items which are part of the canon of Camp” are illustrative of the aesthetic, and worth reading in full, but they include Tiffany lamps, “the old Flash Gordon comics,” Swan Lake, and “stag movies seen without lust.”

Of Sontag’s 58 “jottings” on the topic, here are a few that feel especially useful today:

25. The hallmark of Camp is the spirit of extravagance. Camp is a woman walking around in a dress made of three million feathers.

24. When something is just bad (rather than Camp), it’s often because it is too mediocre in its ambition. The artist hasn’t attempted to do anything really outlandish. (“It’s too much,” “It’s too fantastic,” “It’s not to be believed,” are standard phrases of Camp enthusiasm.)

55. Camp taste is, above all, a mode of enjoyment, of appreciation—not judgment. Camp is generous. It wants to enjoy.

38. Camp is the consistently aesthetic experience of the world. It incarnates a victory of “style” over “content,” “aesthetics” over “morality,” of irony over tragedy.

41. The whole point of Camp is to dethrone the serious. Camp is playful, anti-serious. More precisely, Camp involves a new, more complex relation to “the serious.” One can be serious about the frivolous, frivolous about the serious.

27. What is extravagant in an inconsistent or an unpassionate way is not Camp. Neither can anything be Camp that does not seem to spring from an irrepressible, a virtually uncontrolled sensibility. Without passion, one gets pseudo-Camp–what is merely decorative, safe, in a word, chic.

58. The ultimate Camp statement: it’s good because it’s awful… Of course, one can’t always say that. Only under certain conditions.

While Sontag is the main inspiration for the exhibit, the Met will not restrict itself entirely to her definitions. Failed seriousness is a major theme, but it’s important to note that not all examples of camp are supposed to be serious; indeed, as Bolton told the Times, “when [something] is ‘campy,’ it is more self-conscious, but we are going to look at both.”

Is camp another way of saying “gay”?

“[T]he history of Camp taste is part of the history of snob taste,” Sontag writes. “But since no authentic aristocrats in the old sense exist today to sponsor special tastes, who is the bearer of this taste?”

What arose in the absence of true aristocrats, Sontag wrote in 1964, was “an improvised self-elected class, mainly homosexuals, who constitute themselves as aristocrats of taste.”

Indeed, considering the level of vitriol around homosexuality in the 1960s, it’s easy to imagine the appeal of camp, which embraces a kind of performance of identity. But the association of camp with gay culture led to the over-simplification of the term, which eventually fell out of favor after it began to mean “flamboyant” or even was used to mean “gay-seeming” in a derogatory way.

While the Met exhibit is presenting the more nuanced definition of camp that Sontag outlines, the term still has a demeaning connotation to some, even among the connoisseurs and creators of camp. Just last year, writer Amelia Abraham described an interview she did with the unquestionably camp filmmaker John Waters in Vice: “I mentioned the word ‘camp’ offhand and he sounded shocked. ‘Camp!’ he exclaimed—’I don’t know anyone that would ever say the word camp out loud, it’s like an 80-year-old gay man in a 1950s antique shop under a Tiffany lampshade.'”

Fashion is camp

Today’s most prevalent trends—from the rise of ugly footwear to the downright freaky ensembles that designers have sent down the catwalk over the past several years—reek of camp. “Camp is art that proposes itself seriously, but cannot be taken altogether seriously because it is ‘too much,'” Sontag writes.

Some of the most consistent over-the-top fashion is coming from Balenciaga under Demna Gvasalia and Gucci under Michele, and both will be represented in the Met exhibit. Balenciaga—with its platform crocs, fanny packs, and Comic Sans-printed dresses—is openly subversive, so much so it has been accused of “trolling” consumers.

Likewise, in an ode to the absurd, Gucci sent models down the runway holding their own severed heads in 2017:

Alessandro Michele also presented an aesthetically campy collection this year:

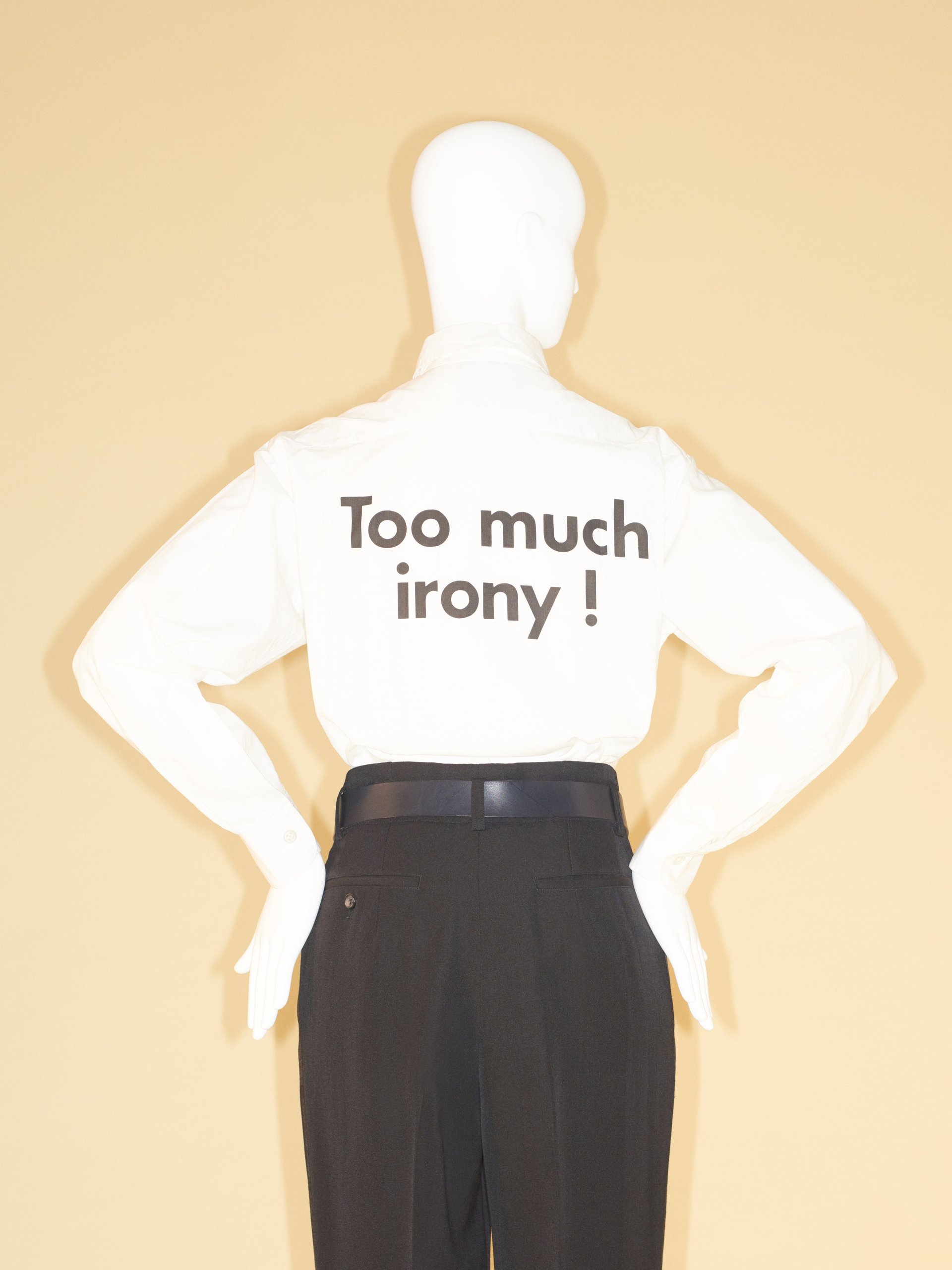

Camp’s irony tenant is also exemplified by Virgil Abloh for Off-White, with his use of quotation marks, which allow him “to operate in a mode of ironic detachment,” the designer explained in a 2017 interview in 032 magazine:

John Galliano, the iconic camp-maker now at Margiela, was busy doing camp at Dior 15 years ago:

As Riccardo Slavik wrote for Collectible Dry in 2017, Galliano’s spring 2004 collection was “a perfect example of Fashion Camp, a show that fused Ancient Egypt, extreme volumes, Cleopatra-in-space drag queen makeup and total impracticality in an iconic way, totally disregarding any thought of sales or wearability… it is camp because it both succeeds and fails so spectacularly.”

Other designers in the exhibit include Charles Frederick Worth and Miuccia Prada, as well as Rei Kawakubo for Comme des Garçons (who was herself the subject of the Costume Institute’s exhibit and gala two years ago).

Donald Trump is camp

With his lurid golden bathrooms, bombastic reality TV persona, gaudy properties, and affinity for trashy celebrity, Donald Trump was a caricature long before he became US president. As Bolton suggests in calling Trump a “very camp figure,” his mannerisms, vulgarity, and personal style have infused our times.

Indeed, Sontag could have had the current US president in mind when she wrote these lines in 1964: “The new-style dandy, the lover of Camp, appreciates vulgarity. Where the dandy would be continually offended or bored, the connoisseur of Camp is continually amused, delighted. The dandy held a perfumed handkerchief to his nostrils and was liable to swoon; the connoisseur of Camp sniffs the stink and prides himself on his strong nerves.”

Music is camp

The picture of Lady Gaga in her infamous “meat dress” is a study in camp, and just as high camp was the pop star’s recent water-taxi arrival at the Venice Film Festival to promote A Star is Born—as a “platinum Aphrodite borne on the waves, black stilettos skimming the sea foam,” according to the New York Times. The pop star and actress carries off these performances with a devastatingly deadpan delivery, recalling again Sontag’s words: “In naïve, or pure, Camp, the essential element is seriousness, a seriousness that fails.”

Both autotune and mumble-rap have been raked over the coals by serious vocalists and lyricists. But excessive autotune (like that of the rapper T-Pain) is perfectly camp: grave in its attempt but intentionally absurd in its execution.

Similarly camp is the anthem “Believe” by Cher, who arguably pioneered the use of autotune:

Meanwhile mumble-rap, a style of rap marked by its incomprehensible—literally “mumbled”—lyrics has been derided for its lack of serious content. But arguably, by prioritizing style over content, mumble-rap becomes “so-bad-it’s-good” camp.

The singer and entrepreneur Rihanna also deserves an honorable mention in the pantheon of camp musicians, particularly for her Met Gala looks of the past several years:

Sneakers are camp

Fashion’s recent embrace of gleefully, garishly ugly sneakers is a triumph of camp. The trend began around 2015 and took serious hold in early 2017, when Vetements released a hideous $650 version of Reebok’s Instapump Fury.

Today, most high-end designers have released their own takes on the absurd, chunky sneaker, from Louis Vuitton to Prada to Margiela.

But the undisputed king of the ugly sneakers is Balenciaga’s Triple S:

Sontag might as well have had a pair of these monstrosities laced to her feet when she wrote: “The discovery of the good taste of bad taste can be very liberating… Here Camp taste supervenes upon good taste as a daring and witty hedonism.”