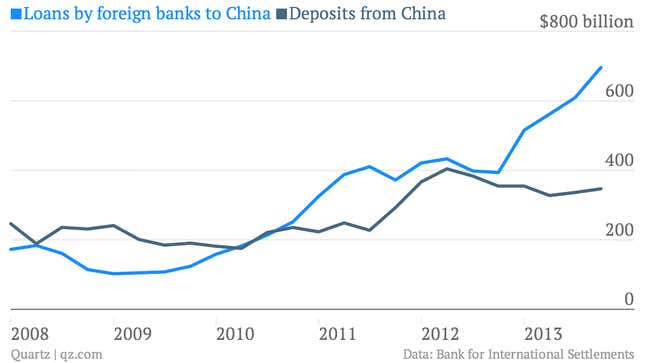

China’s external debt is exploding. The $38 billion in foreign-currency loans that Chinese companies had borrowed from US, European and Japanese banks in the fourth quarter of 2012 had multiplied to nine times that amount by that same quarter in 2013—to more than $349 billion, according to the most recent data from the Bank for International Settlement (BIS). Counting claims by Hong Kong banks, those debts now easily exceed $1 trillion (pdf, p.5).

This is scary-sounding stuff. Just the phrase “external debt” evokes Argentine sovereign debt default, a Thai-style currency crisis or the litany of other catastrophes that occur when emerging-market economies borrow too much abroad.

But many argue that, thanks to its $3.95 trillion in foreign-exchange reserves and its closed capital account, China needn’t worry about such problems.

Those arguments make sense. Unlike other emerging-market countries, China doesn’t need those foreign currencies to finance trade or overseas investment. It borrows because those foreign loans are an easy source of the money that China’s financial system needs to keep banks lending to each other, preventing unprofitable Chinese companies from defaulting—and thereby allowing China’s leaders to promise 7.5% GDP growth this year.

But just as China’s relationship with external debt is different from other emerging-market countries, so too are its risks.

While rising torrents of foreign borrowing keep its system liquid, they have also left China’s central bank with less control over the financial system than it had just two years ago. And that reliance on foreign borrowing makes the country much more vulnerable to a liquidity seize-up than many—including China’s leaders—realize.

Where did all those greenbacks go?

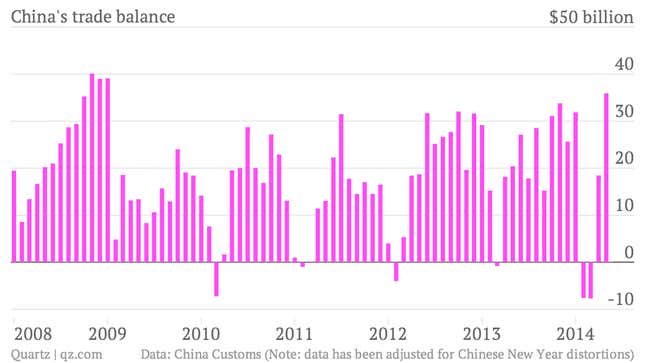

To understand how China’s capital inflows have evolved so rapidly, let’s first start with a riddle. In May, China posted a $36-billion trade surplus, its biggest since January of 2009.

Now usually when the world wants more stuff from China than China wants from the world, it drives up demand for the yuan, since Chinese exporters accepting foreign currency (which we’ll generalize as ”dollars” in this piece for convenience) need to pay their expenses in yuan. On top of that, the mammoth trade surplus was one of a slew of indicators suggesting the Chinese economy was stabilizing, implying the currency has more room to strengthen.

That demand for yuan should make it strengthen against the dollar, driving up the price of China’s exports relative to those of other countries. Big inflows of dollars caused by trade surpluses normally whip the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) into a dollar-buying frenzy, with the central bank selling yuan and adding more dollars to its foreign exchange reserve in order to counteract that yuan-demand (more on those mechanics here). Especially when, despite upbeat economic data, the Chinese economy is still looking peaked enough to need that extra export fillip.

Last month, however, Chinese banks (a proxy for the PBoC, given that they typically sell dollars on to the central bank) bought a measly $6 billion in May:

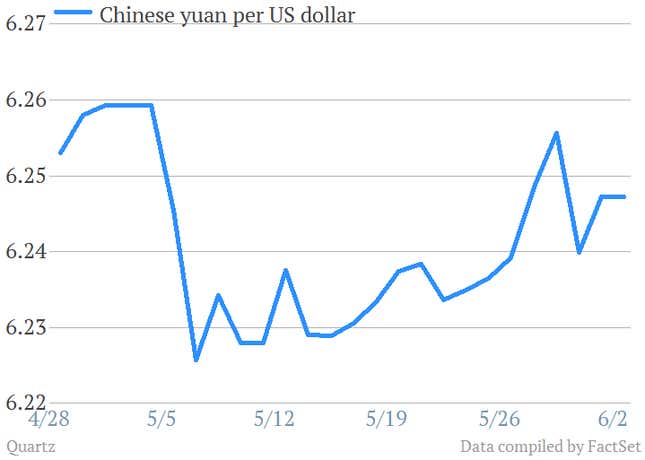

Without the PBoC’s intervention, the influx of dollars from that $36 billion trade surplus would usually drive up the value of the yuan, vis-a-vis the dollar. It did, but just barely. After a small bout of strengthening, the yuan closed out May less than 0.2% stronger than it had started the month.

Why Chinese companies swap yuan for dollars

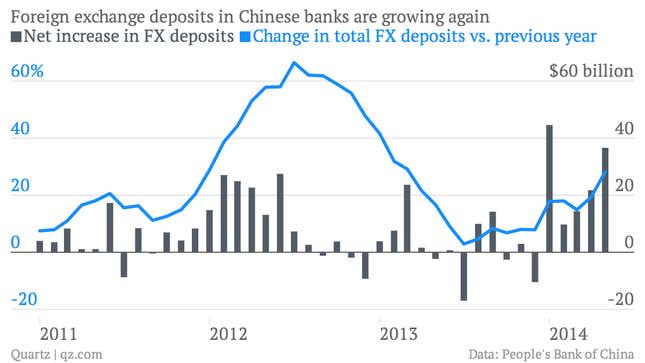

So where did those dollars go, if they weren’t purchased by Chinese banks? The answer to the riddle of the missing greenbacks is that Chinese companies started hoarding dollars big-time in May. (Though China’s capital account is closed, the government allows Chinese trading firms to borrow dollars from offshore banks to manage currency risk.)

But why? What would prompt a Chinese company to hold their deposits in dollars, all of a sudden? The answer goes back to that external debt.

Say that company had borrowed in dollars from a bank offshore, changing them into yuan in the mainland. But when the yuan—or something that influences the yuan, like the state of the Chinese economy—starts to look shaky, the safe thing to do is to change those yuan back into dollars. Otherwise the company risks owing more yuan for every dollar of their offshore debts when those come due. Even if they don’t have to pay those debts immediately, accumulating dollars now protects them against losses later if the yuan keeps shedding value.

In other words, whether Chinese companies convert their dollars depends on whether they are bullish or bearish on the yuan.

Flashback to 2012

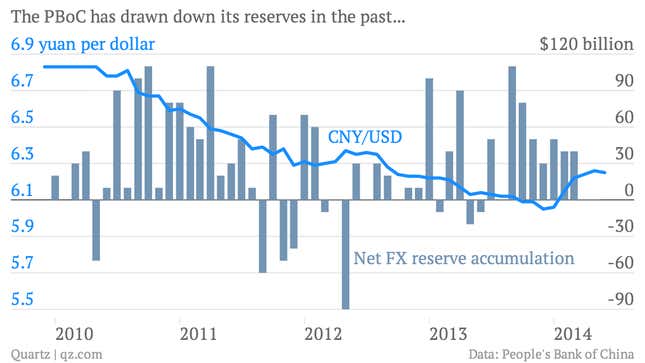

You’ll notice in the chart above that 2014 looks a lot like late 2011 and early 2012. Dollar deposits became popular around then, likely in response to the abrupt weakening of three things: the housing market, the economy, and the yuan. The housing market began slowing sharply in the last quarter of 2011, continuing into the new year. Then in the first quarter of 2012, economic growth fell unexpectedly, says Andrew Polk, an economist at The Conference Board, a research group.

“In 2012, people were expecting the economy to go back up to 8%—some analysts were even saying 10%. But the economy really underperformed; it hit [7.6% in Q2],” he says. ”By the middle of the year, currency expectations [that the yuan would keep weakening] became pretty entrenched. So you see foreign currency deposits build up and then potentially what it looks like is that people started moving them offshore.”

And it wasn’t a small sum—about $225 billion (paywall) seeped across China’s borders from September 2011 to September 2012, according to the Wall Street Journal’s tally.

One of the key things the PBoC did to stop that outflow of capital, says Polk, was to strengthen the yuan against the dollar, pushing the currency’s value up nearly 2.2% between August and December of 2012.

Déjà vu all over again?

Similar to what happened in 2012, the economy started looking shaky at the beginning of this year, led by the housing market’s rapid deterioration in late 2013. The yuan, too, began weakening. And now dollar deposits are jumping. But despite the obvious similarities, one thing has changed dramatically.

China’s new creditor: foreign banks

In the first five months of 2012, as the economy sagged, Chinese companies deposited $34 billion in dollars in their bank accounts. During that same period of 2014, that sum had surged to $127 billion. To whom do they probably owe those dollars?

Foreign banks, mostly. As mentioned above, by the fourth quarter of 2013, the latest period for which there is data, Chinese net borrowing from foreign banks had mushroomed to nine times what it was a year earlier, according to BIS:

The weird world of Chinese trade finance

Some foreign banks lend directly to Chinese corporate customers. But another portion of what foreign banks are actually lending to China isn’t what most people think of when they hear the word ”loan.”

For instance, these loans aren’t necessarily issued directly from a foreign bank to a Chinese corporate customer; they’re often first loaned to a Chinese bank that needs dollars to meet the borrowing needs of its mainland customers in the export/import business. The majority is short-term—usually between three and six months—and issued in the form of trade finance instruments such as ”letters of credit” (LCs) instead of loans.

Generally speaking, these are agreements between an exporter and an importer on payment and delivery of goods, that use a bank to help guarantee the transaction. But since China’s closed capital account prevents the free flow of money over its borders, it’s a little more complicated than that. Here’s how it works: the Chinese bank issues a LC to a Chinese company when it presents a trade order, which the bank then uses as collateral for dollar loan taken out in its Hong Kong branch. The amount is switched back into yuan and deposited into the trader’s mainland account. When the loan comes due, the trader pays back that mainland branch office in whatever currency suits. The branch then turns around and settles the payment with its Hong Kong office.

Since this kind of finance is short-term, backed by underlying business activity, and ultimately guaranteed by Chinese banks as the counterparties, foreign banks consider these loans to be generally un-risky. This business has opened up in part because, comforted perhaps by China’s sterling external credit ratings and its relatively strong economic growth, foreign banks have grown willing to lend.

As for customers, they benefit from cheaper interest rates on offshore dollar borrowing or, if they’re borrowing indirectly, the on LCs at Chinese banks, which average around 2.5% for six months—much less than what it costs to take out a loan to pay for importing goods.

Chinese banks, meanwhile, are keen on this booming business for different reasons. Slowing growth in yuan deposits has left them with less and less to loan out—making it harder to earn money. Issuing LCs and facilitating dollar loans lets them boost revenue with commission fees. And even though the LC rate is piddling, banks still get better interest margins; since China’s banking regulator doesn’t count LCs as loans, the bank doesn’t need to set aside capital or a deposit buffer against the LC. In many cases, they require margin deposits, helping bump up their lending base.

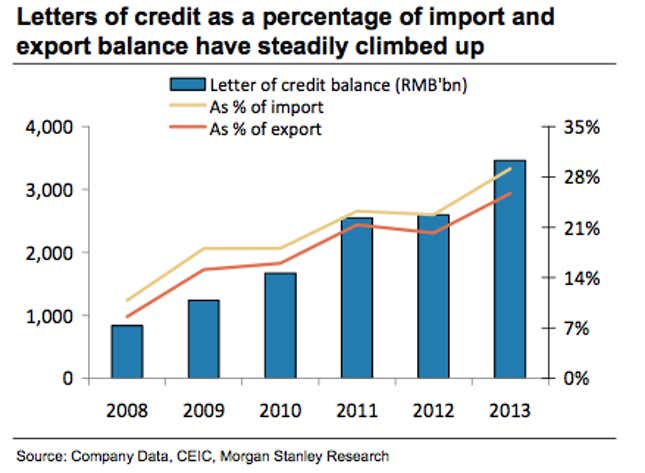

The Chinese government doesn’t track the use of LCs. However, Richard Xu, an economist at Morgan Stanley, estimates that Chinese banks currently have issued about 3 trillion yuan ($482 billion) in outstanding LCs, with the volume of LCs issued outpacing Chinese trade growth in 2011 and 2013.

For a country with $3.95 trillion in foreign reserves, this is kind of strange, says Victor Shih, a professor at University of California, San Diego, and an expert on China’s political economy.

“You have to ask yourself, ‘Why do Chinese banks need so much foreign currency?’ It makes no sense,” Shih says. “China supposedly runs a huge trade surplus. And there’s a lot more inward foreign direct investment into China than outward. So you would think that they have enough dollars to finance whatever trade needs that they have.”

So if the Chinese companies don’t need those dollars to finance trade, what do they need them for?

China’s booming trade in fake trade

In fact, quite a few Chinese borrowers for dollar loans are faking their trade transactions, as we’ve reported in the past. Instead of financing exports or imports, some Chinese companies are borrowing from offshore banks in order to profit from cheaper dollars and lower interest rates than those to be had on the mainland (economists call this a “carry trade”). They then invest those yuan in high-yielding things like real estate or wealth management products, retail investment products that fund risky projects via China’s off-balance-sheet shadow banking system.

As long as the yuan keeps strengthening against the dollar, a company can be confident it will profit both from the currency’s rising value and difference between the overseas interest rate and those it receives on the mainland, which in 2013 could exceed 15%.

It’s impossible to know for sure what percentage of trade finance is fake. But it’s clearly big. For instance, in Q4 2013, China’s trade surplus was only $91 billion, a lot less than the $349 billion in foreign loans (or $1 trillion, including claims by Hong Kong Banks)—and that’s ignoring the fact that some of those $91 billion in recorded exports that came from fake invoicing.

Not all of that is backed by foreign lending. And some of it is for legitimate trade. And again, compared to the overall $22.7 trillion in debt, according to some estimates, $1 trillion in foreign loans really isn’t all the much.

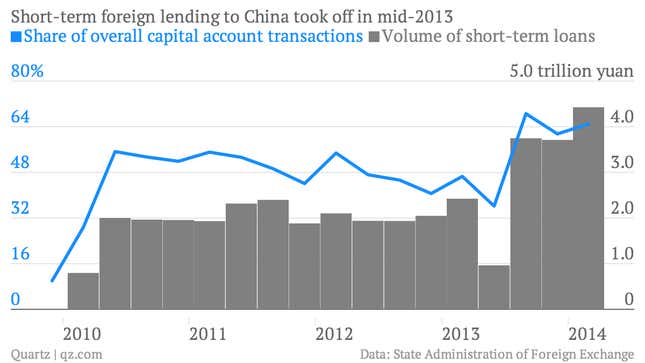

What we do know, however, is that these short-term speculative inflows are claiming a rising share of the overall stream of money pouring into China, as you can see in the official capital account data (link in Chinese):

The PBoC’s February surprise

Of course, it’s not like the Chinese government is oblivious to all this. It might seem odd that China’s leaders let this trade to flourish when one of the big reasons they’ve stalled opening up the capital account is the worry that doing so could allow capital flight to hobble the financial system, the way it did to their neighbors during the Asian financial crisis in 1997.

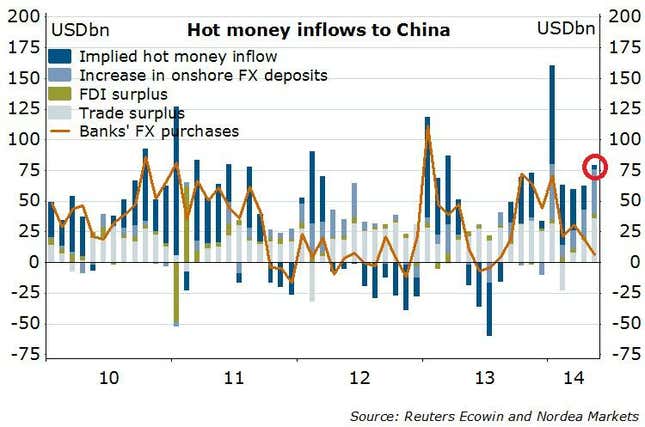

Given what happened in 2012, it’s not a strictly theoretical fear, as we mentioned before. Plus, when these sorts of inflows surge, the demand for yuan ups its value, as we mentioned before, pummeling exporters—terrible news for a country where leaping labor costs are already driving manufacturers to Vietnam and Bangladesh. In 2013 alone, some $500 billion of this “hot money,” as it’s sometimes called, flowed into China, largely via the fake-trade channels.

As you can see in the above chart by Nordea Markets’ Amy Yuan Zhuang, those inflows were still massive going into 2014. What’s changed?

Unlike in 2012, the big drop in the yuan’s value wasn’t caused by darkening economic outlook; the PBoC engineered it. In an unexpected move, starting in mid-February, the PBoC began pushing down the yuan’s value; the currency is down 3% in value since the end of January.

Why would the central bank risk encouraging a reprise of 2012, when Chinese companies started buying up dollars and wiring them out of the country? While it’s widely assumed that the PBoC did this to discourage companies from sneaking in “hot money” to bet on the yuan’s appreciation, it probably didn’t hurt that cheapening the yuan boosts export competitiveness. Finally, the PBoC likely hoped to slow the amount of money flowing into risky investments via shadow banking channels.

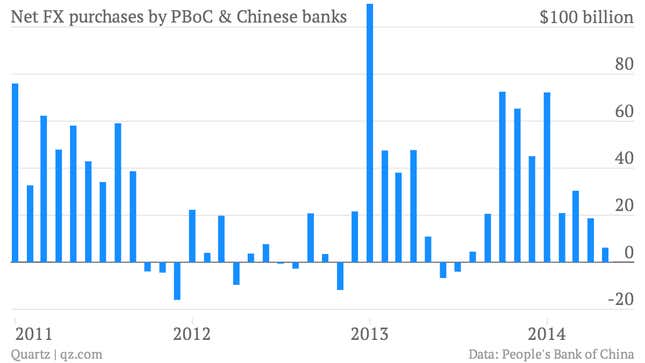

However, Shih says the government had another goal as well. Tellingly, not only did the PBoC cause the yuan to weaken by setting its trading range unusually low, but it also aggressively bought dollars for yuan, creating a glut of liquidity:

“The PBoC printed renminbi, pumped it into the market and bought dollars—and that artificially increases the money supply and drives down interest rates,” says Shih. “I’m sure they moved the renminbi also to punish speculators, but another objective, which they accomplished, is to generate money supply—thereby driving the interest rate down and satisfying the political objective of the Chinese government to keep growth momentum at 7.5% this year.”

Foreign-currency trade finance: a big bonus for the PBoC

The reason China’s leaders accept the risk of 2012-style capital flight, says Shih, is the same reason that they engineered the yuan’s February decline: liquidity.

Until recently, the PBoC’s foreign-exchange reserves supplied the dollars Chinese traders needed to buy overseas goods. Through a couple layers of bank bureaucracy, what essentially would happen is that the company would hand its yuan to the PBoC in exchange for dollars it ultimately forked over to the foreign exporter.

“The renminbi literally gets destroyed—it leaves the money supply, and that causes deflation,” says Shih. “Meanwhile, the PBoC is trying to rollover all this domestic debt, so they want the money supply to keep expanding.”

Put a little differently, China’s use of investment to drive growth allowed companies to borrow heavily; as the economy slows, squeezing the cash flow they need to repay debts, the only way to prevent mass default is for Chinese banks to keep re-extending loans (called “rolling over” loans or “evergreening”). Banks aren’t getting paid, but if China’s going to even dream of hitting that 7.5% GDP growth target, they have to keep issuing new loans. So the government has to keep finding ways to shunt more money into the financial system.

Enter foreign lenders.

The PBoC prints yuan, hands it to Chinese banks, which print up LCs for Chinese companies (or help facilitate the trade credit directly with a foreign bank). Foreign banks then issue dollar loans with the LC (or an asset) as collateral, and those dollars are swapped for yuan, given back to the Chinese company, which then invests it in China. Et voilà—instant liquidity, no deflation.

Or, at least, no deflation as long as the money keeps coming in. Shih’s point explains why capital outflow is so dangerous; once Chinese companies start switching their deposits to dollars, they’re draining liquidity once again.

Collateral damage

But it’s not just the whims of Chinese companies that determine this. By relying on foreign lenders to create China’s liquidity, the PBoC has loosened its control over money supply as well.

So far, it doesn’t seem to have mattered to lenders that, even though this dollar-lending is technically short-term, in practice economists think Chinese banks are rolling over many billions of these debts indefinitely.

Why would banks do something so risky? Because Chinese companies have produced collateral against the loans. One popular form is metal, which Chinese borrowers can store in what are called bonded warehouses in Chinese ports that secure the metal as collateral. By some estimates, nearly one-third of all short-term foreign-exchange loans are backed by commodities such as copper or steel.

The problem, as we’ve covered in the past, is that Chinese companies sometimes pledge the same collateral to take out different loans. That means if the loans go bad, a slew of creditors are left with competing claims to the same hunk of collateral.

The curious case of the 123,000 tonnes of missing metal

That brings us to the scandal now rattling Qingdao, the seventh-busiest port on the planet. State-owned Citic Resources Holdings, a mining and trading company, recently admitted that it couldn’t find 123,500 tonnes (136,000 tons) of alumina—about $50 million worth—that it had stored in a Qingdao warehouse. Both Chinese and Western banks—including Citigroup and Standard Chartered—have issued loans backed by collateral that’s supposed to be sitting in the Qingdao port, according to the Wall Street Journal (paywall).

It might seem strange that it took 123,000 tonnes of alumina to disappear for Western banks to take notice of China’s risky business practices. Then again, companies that are state-owned seem safe, since they’re in theory guaranteed by the government. Loans backed by collateral should also be safe. As for interbank lending, foreign banks have tended to calculate the risk of the Chinese bank they’re lending to, not the underlying risk of where that money ultimately ends up.

Recalculating risk?

The emergence of more Qingdao-like episodes could change that calculus. Already, Standard Bank and GKE Corp, which is partially owned by Louis Dreyfus, have warned that they might suffer losses related to Qingdao port collateral, reports the South China Morning Post reports (paywall)—and Standard Chartered says it’s now reviewing its metal financing to certain Chinese companies.

Those are the banks that have direct exposure to Chinese companies. In the case of LCs and other loans funded via interbank lending, that “would suggest that the ultimate credit exposure comes from Chinese banks,” says Silvercrest Asset Management’s Patrick Chovanec, an expert on the Chinese economy, though he adds that it’s not always clear where the ultimate risk lies.

Still, UCSD’s Shih says a lot of these loans aren’t hedged (meaning protected in the case of a sharp drop in the yuan’s value). If more foreign banks start worrying that some of their loans too are supported by a vanished heap of metal, or sponsored by a Chinese bank will flimsy risk management or unhedged lending practices, they too might become more skittish about lending to China.

Sudden stops

One of the biggest fears that arises when a country comes to rely excessively on external debt is what’s called a “sudden stop.” That’s what happens when the net flow of money into a country slows sharply or stops, either because foreign investors slash investments, creditors stop lending, or domestic residents move their cash out of the country.

Yanking money out of an economy tends to drive down asset prices in sectors such as real estate, igniting a banking crisis, and can shrivel the value of a country’s currency. A chain reaction of sudden stops caused the Asian financial crisis in 1997.

3.95 trillion reasons why China’s unlike other emerging markets

Could China experience a sudden stop if foreign lenders started refusing to let Chinese companies roll-over loans, or if they cut back on lending altogether? Not likely, says Silvercrest’s Chovanec.

China’s $3.95-trillion foreign exchange reserve gives it plenty of money to pay foreign debts and maintain the yuan’s value, he says, making it different from most countries that have watched their economies implode due to sudden stops. Plus, foreign loans aren’t even one of China’s primary sources of funding; they’re just one channel flowing into China’s $5-trillion shadow banking system.

“I’m not saying [external debt is] not an issue, but it’s really more of domestic issue. The problem is fundamentally the reliance on runaway credit expansion of all kinds of channels, rather than a particular reliance on foreign funding like Southeast Asian countries in the 1990s,” says Chovanec. ”Like all those forms of credit expansion, if [foreign-currency loans] were reined in at any point, it could create big problems.”

External debt is still debt

But if the PBoC has ample reserves with which to keep its currency stable, what problems could a sudden outflow of dollars create?

“To me the biggest risk is not that foreign currency loans are big enough that they could create a sudden stop like in Argentina, but that the PBoC doesn’t react to liquidity conditions in the proper way,” says The Conference Board’s Polk. “They could create their own liquidity crisis by underestimating the scope of what foreign currency flows can do.”

Take, for example, the abrupt disappearance of liquidity after the PBoC cracked down on fake trade invoicing in May 2013. The central bank then exacerbated this crackdown by handling it in a way that Polk describes as looking ”pretty hamfisted,” causing China’s financial system to freeze up for a week and prompting money to flee across the border to Hong Kong. That episode could mean the PBoC simply doesn’t grasp how much capital is flowing in and out of China.

Still, even if foreign-currency lending were to cause another cash crunch, the PBoC at least knows now that it would need to print more money as it uses its reserves to meet foreign debt obligations. That likely means no external debt crisis. But what about a regular debt crisis? As Michael Pettis, a finance professor at Peking University, highlights in a recent note, this gets to the core quandary facing the PBoC. ”The problem in China,” he writes, ”is not the stock of foreign debt but the commitment to a growth model that requires an unsustainable rise in debt simply to keep the engine running.”