From Hong Kong to Lebanon, and Sudan to London, this was the year of the protester.

In Sudan, the protests kicked off over an increase in bread prices, and then went nationwide, culminating in the ousting of a leader of three decades and—after civilian bloodshed—a civilian-military effort to work toward elections. In Hong Kong, they began over a piece of legislation that crystallized the city’s simmering fears that it will slowly lose the freedoms and framework that render it distinct from the rest of China—and are continuing six months later.

In Lebanon, they kicked off over a proposed tax on WhatsApp calls that morphed into a wider criticism of corruption and the mishandling of the economy—leading to the resignation of the prime minister. In Catalonia, they erupted in response to the lengthy sentences for separatist leaders who backed an independence referendum. In India, new citizenship rules that discriminate against Muslims deepened fears that the country, under its Hindu nationalist government, is crafting a Hindu republic. And in Chile, a campaign started by students to protest a fare increase morphed into a broader protest against an economic structure shaped by an era of neoliberal military rule.

In many cities, it was the looming climate disaster that drew people to the streets.

Protests also took place in a number of other countries, reflecting a moment when it is much easier to call masses of people to the streets than before—but often harder to build an ongoing, resilient movement that can go the distance. Quartz reached out to people who were at some of 2019’s protests to find out what it was like to be there.

Sudan: “Freedom, peace, and justice”

Samah Jamous, 29, dentist from Omdurman

I went to join a protest in downtown Khartoum. It was small, only a hundred. When it started, security officers arrived in five minutes, surrounded us from all sides, and began arresting us. I ran with others into a nearby clinic and saw a family in the waiting room. I told them I was a doctor visiting the clinic, surprised by the protest, but security officers were trying to arrest me.

They offered to help, quickly introduced me to everyone and gave me the mother’s appointment papers. When the officers came in and saw me, the family told them I was one of their daughters. One officer tried to grab me but the mother shouted “What are you doing? That’s my daughter!”

And it was clear that I didn’t resemble them. They came from Halfa El-Jadida in eastern Sudan and my family is from Darfur in western Sudan. They even separated us and started questioning each person individually. At one point, the mother placed a blanket on the floor, lay down and asked me to join her. She hugged me and we began chatting. Her name was Salama [Arabic for “safety”].

Three hours later, when the security officers left, she smiled and said “we saw you from above, you came with the protest.” That was the moment I realized we were not alone. They didn’t know me or anything about me. You don’t play around with security officers in a situation like this. They took a risk. Not everyone was in the streets, but their hearts were with us. I knew then there will be a moment when everyone will be on the streets. —as told to Isma’il Kushkush

Hong Kong: “Five demands, not one less”

Adrian, 20s, finance professional

There has been no shortage of cinematic moments in the movement, but none come close to this one. It was the morning of Nov. 18, hours after the police laid siege to the Polytechnic University. Over a thousand civilians were trapped at the university, as they would get arrested the moment they left the campus.

The night before, there was fear that protesters inside the campus would run out of resources and police could violently crack down on the campus and arrest the militant protesters, who have been the major force that has kept the momentum of the protesters from dwindling.

A tear gas canister deflected off my umbrella. I swiftly huddled behind the trash cart. It didn’t take me long to realize that Saving Private Ryan would be a long shot. With just bricks and a few fire bombs, it would be impossible to advance through the riot police, let alone to reach Polytechnic University.

“Save Poly!” a voice came from behind me. “Save Poly!” another echoed. Reaching the campus may have been a long shot, yet the morale among us had never been higher.

The next morning, I changed to the “normal” outfit that I prepared, packed my goggles and gas masks, and tried to get closer to the campus. I found a way along which I could get close to the campus, though riot police were standing in our way. Again, it was virtually impossible to get through. All of a sudden, though, a flock of protesters dashed out from the campus, running towards the harbor crossing tunnel.

“Come here!” a crowd shouted from behind the barbed wire. They seemed to notice us. Some turned around and started running towards us. The police, unsurprisingly, started to fire tear gas canisters again, trying to rift and wedge the fleeing protesters. A tear gas canister flew right by my ear, missing by just a few inches.

A protester climbed up and over the barbed wire and I caught him. He could barely walk. Injured? Exhausted? I don’t know. I was left with no room to think about that. He put his arm across my shoulder and we hobbled to a safe spot away from the police, where he immediately slumped down. I could finally see his face when he took off his gas mask. I am in my early twenties and he was probably 10 years younger.

He laid his head on my thighs and just started sobbing, and so did I.

“You are free,” I kept telling him. —as written to Mary Hui

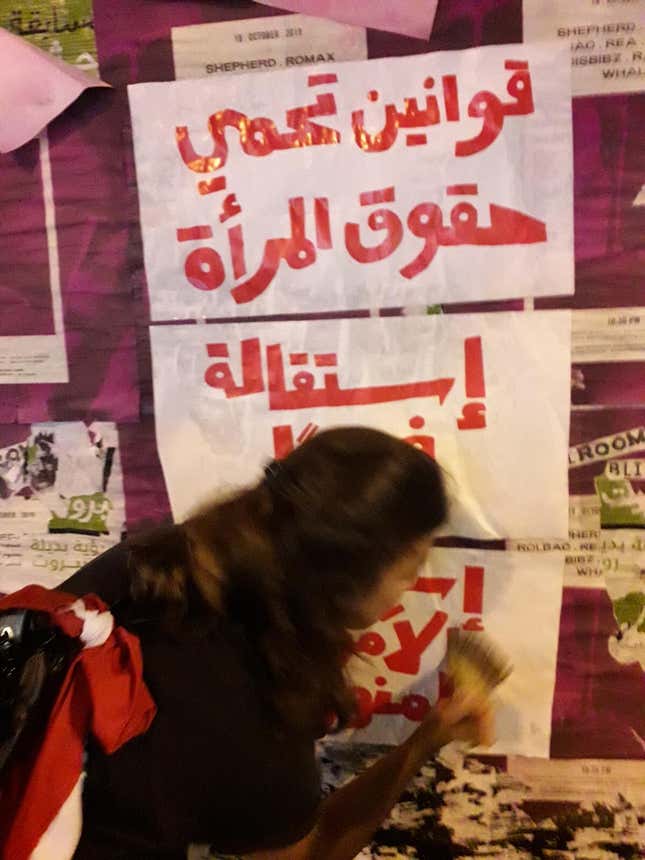

Lebanon: “All of them means all of them”

Sandra Geahchan, 28, trainee lawyer

Responding to a call for volunteers to close down the “Ring” Bridge for the first time, I arrived there on a Saturday morning in late October. Standing on the side of the express road separating East and West Beirut, I contemplated the risk, as well as the symbolism of what we were about to do.

The “Ring” was the arena of intense infighting through the whole of the 1975-1990 civil war as it sat on the demarcation line that separated the two warring sides of the city. For the previous generation, memories of the bridge in rubble and emptied out of its cars is a traumatic and ghastly one.

The middle-aged man next to me warned us “don’t go in there, bannout (girlie), in a few minutes these guys will be cleaned out.”

As I sat down on the hot asphalt, a hand slipped under my arm and held me tight. A woman smiled at me and then continued chanting. We slid closer to the front as the officers tightened their ranks around us. Someone threw roses; I caught one, as water bottles were passed around. I could tell we’d be there a while.

Another woman stood in the middle waving a giant Lebanese flag, energizing the small but growing group with her inexhaustible fervor. She is but one of many women who have acted as a buffer between security forces and protesters since the unrest began in mid-October. Chants grew louder and louder, as years of outrage morphed into a collective release. We screamed like none of us have screamed before.

Once a space of cleavage, the Ring has become a point of unity as protesters flow in from the diverse neighbourhoods it connects to. At a site where our fathers might have fought, this new generation of Lebanese has come together to demand a better future, an end to corruption, and to challenge a system that thrives on division. In a cathartic moment, a memory became strength as we reclaimed another landmark of our history. —as written to Adam Rasmi

London: “Business as usual is death”

Farhana Yamin, 54, environment lawyer

On April 16, Farhana Yamin removed the top from a bottle of superglue and tried to glue herself to the entrance of the London headquarters of the oil giant Royal Dutch Shell. The police were distracted by other protesters who were being arrested at Shell for their “Stop Ecocide” demonstration. Yamin wanted to continue their action, so she ran for it and shouted “I’m glued to the floor!”

Her husband Michael Yule and their son Rafi watched Yamin break the law. She would soon be arrested, along with more than 1,000 other protesters around London. “She’s a lawyer,” Yule told reporters. “She believes in the rule of law. But nonviolent, civil disobedience at some point becomes necessary.”

Yamin is not just any lawyer. She has spent 25 years helping craft international environmental laws such as the Kyoto Protocol, which established the first global carbon market, and the European Union’s Emissions Trading Scheme, one of the world’s most progressive pieces of climate legislation. She has been a lead author of three reports by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the highest global body on the subject. She is really proud of getting the goal of net-zero emissions by 2050 in the 2015 Paris Agreement, which was signed by every country in the world.

But she was done with how difficult it was to get the system to change and act quickly on addressing climate change. Yamin embodies the frustration of the hundreds of thousands of people going on climate strikes around the world, or of Extinction Rebellion’s nonviolent civil disobedience movement. —Akshat Rathi

Chile: “It’s not 30 pesos, it’s 30 years”

Antonella Oberti, 23, law student

On Oct. 25, as I tried to make my way to Baquedano Square in downtown Santiago to meet with my sisters, I could not believe how many people there were on the streets. We still were about 40 blocks from the protest, but hundreds of thousands of people already filled the streets completely, carrying flags and signs. There were a lot of signs that said: “They have taken so much from us, that they even took away our fear.” I also remember one sign in particular that really struck me; it said, “For my mom, who died waiting for her cancer treatment.”

No one knew it yet, but we could feel this was going to be a protest like this country had never seen before—eventually, over 1.2 million people gathered.

I didn’t know anyone there but we walked together all the way downtown, talking about what was happening, the protests all over the country, the “pot bangings” (paywall), the fires in the metro stations, and what everyone thought the best solutions for the country were. Despite having some differences, we all agreed on one thing: We are moving toward a better future, toward a free but just country.

As we approached the square from one of the buildings, a man was playing drums from his balcony. A big group of people gathered right below him, singing and dancing different songs, including “El Baile de Los Que Sobran” (The Dance of the Leftover People) by Los Prisioneros, which has become a kind of anthem of the movement. It was such a cathartic moment: complete strangers coming together in that moment. There was a sign hanging down from the man’s balcony.

It read: “Until dignity becomes a habit.” —as written to Tripti Lahiri

India: “No to CAA”

Ummul Fatima, 21, psychology student

When the Delhi police entered our campus at Jamia Milia Islamia University, I witnessed terror unfolding right in front of my eyes.

I knew students were protesting against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) but had no plans to join them at that point. On Dec. 15, I went to study thinking that even after the chaos, the campus was the safest place to be, but I was wrong.

I was aware that the police had forcefully entered the premises and was bombing our campus with tear gas. Along with some of my friends, I went to the library. Suddenly, we saw some smoke coming in from one of the windows due to the tear gas shells used by the police. We quickly shut all the doors, but 10-15 cops barged in.

They started thrashing the students. It was brutal. The girls tried to save the male students. We hid them and circled around our friends but the policemen were being ruthless with the boys. One of the cops dragged a chair and hit it on the head of my friend. Nobody got a chance to say anything. The confused students were desperately trying to dodge the police somehow. One of the students even fainted after the constant beating, but the cops did not stop.

Their job is to protect us, but they acted like terrorists.

Even as I struggled with the madness of the moment, I knew I would not be able to forgive the police for this. My friends are still scared and healing from the trauma, but now that we have witnessed the worst, nothing can scare us.

We will protest against the CAA until our voices are heard. Their attacks cannot stop us from standing against the wrong. I am more fearless now than I have ever been in my entire life. —as told to Niharika Sharma

Catalonia: “Self-determination is not a crime”

Pau Mir, 22, student from Barcelona

I was in the occupation of the country’s biggest highway, which connects with France, in an action aimed at hindering transport between Spain and the rest of Europe. We managed to cut off cars and trucks for more than 48 hours at two different points. People improvised musical performances in the middle of the road while others built barricades on the edges. We carried food and water to the stopped drivers, overcame the cold with bonfires, and shared our experiences from the previous days at the airport, or on the marches to Barcelona, or at many other recent protests for freedom and self-determination.

Among us there are really different views on the political moment. There are a lot of different concepts about what nonviolent disobedience means. We share the objectives but sometimes don’t agree on the next step or even in the general strategy to follow. But, since this October, I have the impression that we are learning to make the different methods of protest compatible. Everyone can just choose which style of actions they feel more comfortable with, and stick to it, while respecting other kinds of tactics and rhythms.

One year ago, for instance, there were incidents in the street between people that used burning barricades to defend themselves and people who did not want to start any fire because it gave us a bad image at the international level. Now, there are almost no clashes of this kind, and people start believing that the different methods are valid and even necessary altogether. —as told to Mary Hui