The results are in, but the outcome was never in doubt. A controversial referendum in Crimea delivered a huge majority in favor of joining Russia. The West did not recognize the vote, with the White House calling it “dangerous and destabilizing” and the European Union dubbing it “illegal and illegitimate.”

Now what? The EU’s foreign ministers will meet in Brussels on Monday (Mar. 17), when they are expected to announce travel bans and asset freezes on Russian officials. To date, the EU has come in for sharp criticism for shrinking in the face of Russian aggression, caving in to the German exporters, British bankers, and other business interests. But some believe that the incessant chatter that Europe is too soft on Russia may only serve to harden its stance.

“This completely phony referendum is just so absurd that it makes it more difficult for the Russians to make their case to the rest of Europe,” says Ian Bond, director of foreign policy at the Centre for European Reform (CER), a London-based think tank. As a result, “the referendum increases the chance that the EU will go further” than the conventional wisdom expects, he tells Quartz.

Words and deeds

The individuals that the EU targets in its initial sanctions will be telling, as most expect only a small circle of government officials directly related to the seizure of Crimea. The Kremlin forced its officials to repatriate their foreign assets last year, so sanctions won’t hurt loyalists as much today as they would have in the recent past. That said, European diplomats’ initial list of targets reportedly ran to hundreds of names, including key business leaders, so the targets of sanctions may steadily expand in a tit-for-tat response to Moscow’s actions in the coming days.

On Thursday (Mar. 20), EU country leaders will meet in Brussels, and this is when more serious sanctions could be announced, including broader trade and financial restrictions. Much will depend on whether, or when, Russia annexes Crimea and, especially, if Moscow takes a more active role in the unrest now spreading into eastern Ukraine.

German chancellor Angela Merkel had some unusually harsh language for Russia last week, a sign of rapidly fraying relations between the two countries. Equally important were comments from the head of Germany’s powerful export lobby, who said that trade sanctions would be “painful” for Germany but “life-threatening” to Russia.

In London, photographers snapped embarrassing pictures of a senior advisor to prime minister David Cameron carrying a memo that, playing to type, suggested the government would “not support, for now, trade sanctions…or close London’s financial centre to Russians.” Says Bond of CER: “In an odd sort of way, this may have put some pressure on the prime minister to be tougher than he otherwise would have been.”

Guns and gas

There is a good chance that European military deals with Russia will soon be put on ice. These include a billion-dollar deal with France to deliver two warships—one rather awkwardly destined to join the Crimea-based Black Sea Fleet—and a German contract to build a state-of-the-art training facility for Russian troops. “Are you sure you want to do that when they’re practicing for the invasion of Ukraine?” asks Bond.

The extensive energy links between Russia and Europe are another area up for discussion. Although finding a substitute for Russian gas overnight is unrealistic, Europe is much less reliant on Russia than it was only a few years ago. Some countries have already begun building up buffer stocks in case supplies are disrupted. And although formal sanctions against Russian energy providers will probably be avoided, informal obstacles to the energy trade—halting talks on new pipelines and running existing pipes below capacity, for example—are already depriving Moscow of revenue as well as reducing its influence over the continent.

Ratcheting up the pressure

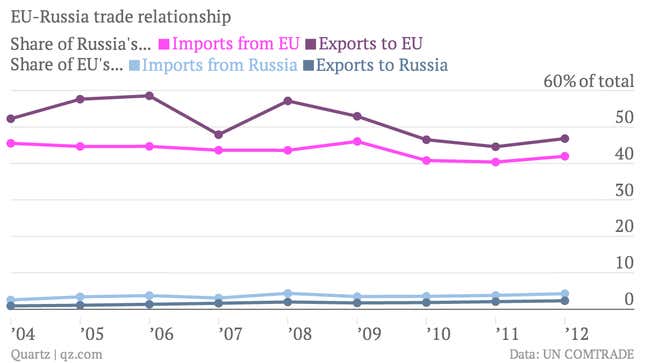

There is no avoiding that broad trade or financial sanctions would hurt a wide range of European companies that do business with Russia. In fact, capital is already flowing as if sanctions are on the way, to these companies’ cost. But if the EU is serious about acting as a unified economic bloc, it would enjoy much greater leverage on trade over Russia than the other way around:

The impact on the Russian economy from the strictest sanctions will be severe, although this seems to be lost on some officials. The boost in popularity that Russian president Vladimir Putin is enjoying at home thanks to his muscular approach in Ukraine may persuade him to maintain a tough line despite sanctions. In puzzling comments earlier this week, Putin was reportedly dissatisfied with his country’s low growth rate and urged the finance minister and central bank chief to “achieve stronger dynamics” (paywall).

Moment of truth

When US secretary of state John Kerry met Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov in London for last-ditch talks on the eve of Crimea’s referendum, European officials were conspicuously absent. Tough action this week from the EU could mark the first step in the union playing a bigger role on the world stage.

If the EU is serious about imposing costs on Russia for its actions in Ukraine, it cannot avoid short-term commercial pain in the service of longer-term geopolitical gain. The West was wrong-footed in the run-up to Crimea’s secession because its perception of Putin’s personality and motivations were out of date. We will soon find out if the perception of the 28-member EU, often parodied as a toothless talking shop when it comes to international affairs, is similarly obsolete.