Imagine this: You’re browsing online and find two different shirts you like. One is from a company you believe to have good business practices. The exact criteria don’t matter so much for this hypothetical, but let’s say it tries to use more sustainable materials and only sources from factories where workers are paid decent wages.

The other shirt is half the price, and is made by a company you know has been linked to environmental pollution and poor working conditions at the factories in low-wage countries it relies on to churn out the huge volume of cheap clothes it sells.

You want to buy one of the shirts, so now you have a choice to make: Do you pay more for the first shirt, or less for the second?

It’s a question shoppers encounter all the time, even if they aren’t always aware of it. Many—probably most—will buy the cheaper option without a second thought. For those that do consider the conundrum, it will likely provoke other questions, like how much difference will any one purchase make?

Here’s a different question to consider: Why is that second shirt available to begin with?

Products that involve exploitative, environmentally destructive, or otherwise harmful business practices somewhere in their making aren’t hard to find on store shelves. They can range from the chocolate we eat to the phones we use. In some cases the practices are plainly illegal and companies are held responsible. Often, though, they toe the boundaries of legality, and companies avoid liability because they don’t own the farms, mines, or factories themselves, instead relying on a chain of independent contractors who bear the legal risks for them.

In these scenarios, it’s generally left to consumers to decide which companies they want to support. It’s the free market at work: Give shoppers options and they will vote with their dollars, the logic goes. Ultimately the good will rise and the bad will fall. Consumers bear a similar responsibility for recycling, or avoiding single-use plastics such as bags and straws.

The paradigm ostensibly puts the power in the hands of ordinary citizens. But in doing so, it puts much of the responsibility for policing companies on them too, when they may not be in the best position to handle the job. It can be hard for consumers to gather all the information needed to make fully informed decisions, and even supposedly ethical shoppers don’t always make ethics the top priority in their purchases.

Lately, an alternative looks to be coming back into fashion, in the form of growing calls for government regulation.

Some jobs are too big for consumers to handle alone

Fashion has emerged as a prime example of an industry shoppers have been left to keep in check through their purchases. Watchdog groups and journalists routinely uncover examples of worker abuses in fashion supply chains, so much so that critics say the business model behind low-cost, high-volume clothing is inherently exploitative. Meanwhile, producing all the raw materials for the world’s clothes, which includes processes like dyeing and finishing massive quantities of textiles, results in environmental issues such as appallingly polluted waterways and large amounts of greenhouse gas emissions.

These issues have attracted more and more public scrutiny over the years, especially as it’s become cool for consumers to care about the environment and social issues. As this awareness of fashion’s ethical drawbacks has grown beyond a niche subset of shoppers, it should theoretically prompt more consumers to change their shopping habits, in turn forcing fashion companies to alter their behavior.

And to some degree, that is what’s happening. Young shoppers in wealthy parts of the world such as the US and western Europe frequently say they want more sustainable clothing. Greta Thunberg, the 18-year-old who has become a prominent face for a new generation of climate activism, recently used her turn on the inaugural cover of Vogue Scandinavia to call out fast fashion’s environmental damage. These sorts of signals have investment analysts wondering whether fast-fashion companies could be in long-term jeopardy.

Many fashion businesses have instituted voluntary measures to improve working conditions in their supply chains or to incorporate more sustainable materials and renewable energy in their operations—part of a broader trend of corporate social responsibility (pdf) that’s been on the rise since the 1990s.

But broadly speaking, either the steps companies have taken haven’t been effective or aren’t happening fast enough to counter the impact of the growing volume of clothing they make annually. Fashion’s use of resources and its carbon output are still on pace to increase dramatically (pdf) over the next few decades, and labor abuses continue to occur. Skeptics say all the corporate campaigning about sustainability is more marketing than genuine change.

Shoppers don’t appear to be shunning companies over these issues, even as more happily buy products marketed as sustainable. Boohoo, an online fashion retailer in the UK, recently recorded a surge in sales after its highly publicized scandal about the working conditions and illegally low pay at its suppliers in Leicester. Shein, a China-based retailer known for releasing new styles of cheap, trendy clothes at an unmatched pace, has taken off among US teens, who represent the generation most concerned about the planet.

In fact, researchers have long recognized an “attitude-behavior gap” among consumers, who often claim to care about the ethical pedigree of the products they buy and services they use but then prioritize their wallets with their actual spending. Researchers have proposed some explanations, such as shoppers being barraged with too much information; being unable to connect any one purchase with concrete repercussions in the complex, multi-tiered supply chains that exist today; and a lack of truly ethical choices to begin with. Shoppers also don’t generally appear willing to put values ahead of other considerations, like flavor in food. While they could very well influence businesses by acting collectively, most consumers don’t, and therefore have less impact than they otherwise could.

Critics such as designer Stella McCartney and Elizabeth Cline, author of multiple books about the industry, contend leaving change in the hands of consumers and companies isn’t doing enough to mitigate fashion’s harmful effects. McCartney, who serves as an advisor to the executive committee of LVMH, the French luxury giant that acts as her financial partner, recently told the trade publication Business of Fashion (paywall) that fashion has fallen short on policing itself. It needs policy to do it.

Cline argues ethical consumerism has had little if any discernible impact, while others say it shouldn’t be left to shoppers (paywall) to punish companies for practices such as exploiting workers in the first place. The best solution, more voices say, is government regulation.

“Individual decisions still matter, especially if it’s a celebrity and an influencer presenting a different way of consuming,” says Maxine Bédat, founder of New Standard Institute, a think tank focused on making the fashion industry more ethical and sustainable, and author of Unraveled, which outlines the social and environmental harms embedded in the garment business. “But I definitely have shifted to understanding the role of policy and legislation and the need for that.”

How we left it to consumers to save the world

It’s hard to pin down exactly how consumer shopping choices became the last line of defense against questionable business practices. There’s a long history of consumers exerting power through their purchases, or more specifically by withholding them, dating back to at least the 1791 boycotts of slave-produced sugar in the UK.

But Terry Newholm, a former lecturer in consumption ethics at the University of Manchester, describes these as “bottom-up” actions coming from consumers. The present paradigm is arguably a situation created from the top down by governments and companies, who pushed responsibility onto them. Bédat and Cline trace its origin to the neoliberal policies that shaped the latter half of the 20th century with help from proponents such as Milton Friedman, the American economist who championed nearly unrestrained free-market capitalism.

As a concept, neoliberalism is a bit fuzzy at the edges, being a collection of overlapping ideas from different theorists. But at its core is a belief in the free market, with government basically just there to set the rules. Friedrich Hayek, the Austria-born economist who was its most prominent voice, viewed the market as a way to deal with the fragmentation and subjectivity of knowledge. Individuals have their own values and interests, he argued, and nobody—government included—is able to have a complete, objective understanding of all the forces at work in the economy. Government, therefore, can’t realistically manage the economy from on high, so it’s best to let individuals compete freely in pursuit of their own interests. The approach would lead to more creativity and entrepreneurship, benefitting society as a whole, he believed.

Friedman offered his take on how corporations should behave in this framework in 1970. In a well-known piece for the New York Times, he argued a CEO is an employee of the corporation’s shareholders with a distinct responsibility: “That responsibility is to conduct the business in accordance with their desires, which generally will be to make as much money as possible while conforming to the basic rules of the society, both those embodied in law and those embodied in ethical custom.” To focus on “social responsibility” and spend money on endeavors such as “reducing pollution beyond the amount that is in the best interests of the corporation or that is required by law” isn’t in alignment with shareholders’ interests, he wrote.

The idea would practically become a mantra for corporate leaders, while consumers in countries such as the US were getting the message that they needed to be more socially responsible. One notable example is the case of glass bottles and other disposable containers, and whose job it was to deal with them.

The rise of individual action

The flood of products that hit the US market amid the post-World War II boom in consumerism brought with it a swell of garbage, much of it in the form of packaging. The glass bottles that once were reused over and over were now treated as disposable, leading to more waste and litter. In 1953, Vermont banned disposable bottles, a move that spooked the packaging and beverage industries. That year, the American Can Company and Owens-Illinois Glass Company joined forces with others such as Coca-Cola and the Dixie Cup Company to form an organization called Keep America Beautiful.

KAB began a campaign of public service announcements targeting littering, but its aim wasn’t selfless. Authors who’ve investigated KAB’s anti-litter messaging say the goal was to deflect focus from regulating packaging.

“Rather than them taking responsibility for all the disposable containers that are replacing the returnable bottles that have been the dominant form of packaging before that, they put all the onus on consumers,” Finis Dunaway, a professor of history at Trent University in Ontario and author of Seeing Green: The Use and Abuse of American Environmental Images, says in an interview. “It’s your fault for carelessly throwing things away.”

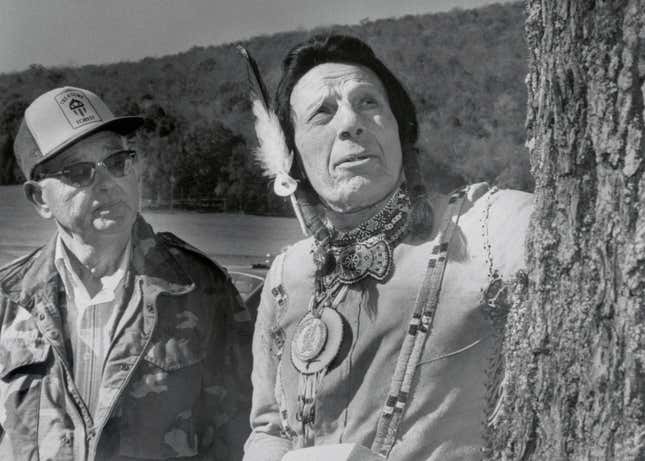

The most famous of its public service announcements, released in 1971, was known as the Crying Indian ad, in which a Native American—actually an Italian-American actor—sheds an expressive tear after encountering scenes of pollution and littering. “People start pollution,” the ad proclaimed. “People can stop it.” KAB’s messaging was remarkably effective. It worked with schools and government agencies, and even attracted environmental groups as advisors. It was only when the organization began to lobby against bottle bills, which would require manufacturers to use returnable containers, that environmental groups cut ties, Dunaway says. Still, the group would influence ideas about the duties consumers bore when it came to issues such as recycling—a practice the oil industry would also push to counter plastic pollution, despite knowing it wouldn’t actually solve the problem.

While corporate managers were making it their mission to maximize shareholder value, the US government didn’t simply give up regulating business. On the contrary, it embraced “social regulation” focused on matters such as consumer health and safety, setting stricter standards for manufacturers in the auto industry and others. (Even Hayek thought government should be able to outlaw unsafe substances.)

But also beginning to take hold was discourse around a consumer’s personal responsibility, which insisted shoppers be free to make their own choices and bear the consequences. In the late 1970s, for instance, while concerns about the health hazards of cigarettes were spreading, the tobacco industry ceased trying to claim smoking wasn’t harmful as a way to avoid regulation. Instead, it began to push the argument that adults are accountable for their own health and should be free to choose whether they smoke or not, according to a study of the rhetoric tobacco representatives used in news coverage and internal industry documents. The end of the Cold War brought further shifts, as it solidified the idea that capitalism and democracy were synonymous, Dunaway explains.

“That time period is very significant because, more and more, individual action is seen as the answer to all kinds of social problems, not just environmental, but that becomes really entrenched within popular culture, within politics,” he says. In the US, social regulations also received new scrutiny from policy makers, who wanted them to be less burdensome and costly.

None of this is to say consumers were simply duped into taking responsibility upon themselves. Many were responding to what they deemed a lack of action from institutions.

“Particularly around environmental issues in the 1980s, you saw a disconnect between where people were in their heads and where government was,” says Rob Harrison, co-founder of the magazine Ethical Consumer, which began publishing in the UK in 1989. “And that led to a response through markets.”

Harrison points to globalization as a major factor too. Companies moved manufacturing overseas to cheaper outposts, putting their operations under the jurisdiction of countries with less rigorous environmental and labor laws. It created regulatory challenges for governments, even if they wanted to step in. “The Dutch government can’t ban child labor in Pakistan,” he says.

Both he and Newholm, the former University of Manchester lecturer, describe ethical consumerism as pushing against neoliberalism. Consumer actions such as the anti-apartheid boycotts of South Africa and the push to ban ozone-depleting CFCs released by aerosols were galvanizing events that showed shoppers could effect change when elected leaders weren’t taking the lead. If corporations weren’t going to prioritize social responsibility and governments wouldn’t or couldn’t make them, somebody had to.

These dynamics helped give rise to the ethical-consumer mindset that grew through the 2000s and has become prevalent today. Companies now attract shoppers with products they promote as sustainable or ethical. In the US, buying organic produce has become a class marker for the elite. Consumers recycle their plastic bottles and feel like they’re doing their part to protect the environment, even though much of it is never actually recycled.

Conscious consumerism wasn’t supposed to be a substitute for laws, though. “My expectations were never that consumers acting rationally in an ethical way were going to somehow magically transform everything,” Harrison explains. The power of consumers is that they can react quickly to problems they see in the market, he says, and those actions “create pressure for regulation to happen down the line.”

The end of neoliberalism and a return to regulation?

The share of the burden customers bear to keep companies in check varies by country. Typically, nations in Europe are more willing to put guardrails on industry, forcing companies to fall in line. “I don’t mean this disrespectfully, but European companies, maybe also due to regulation, have tended to be ahead,” Kasper Rorsted, CEO of Adidas, said at an event on June 16.

The tide may even be turning in the US, where political leaders have often decried government interference in business. Regulation is currently on the rise under president Joe Biden. His administration has set new guidelines—or sometimes restored policies undone by his predecessor, Donald Trump—on a number of issues, from worker pay to methane emissions. Recently, the federal government announced what could be the most significant regulation of greenhouse gas emissions in US history when it reinstated fuel-efficiency standards on gas cars and said it would mandate half of all cars sold in the US be electric by 2030.

These moves have received pushback from industry, but Biden’s presidency also comes with a shift in how Americans more broadly view an unconstrained free market. Younger generations in particular have less favorable views of capitalism, at least as it’s been practiced, linking it with problems such as inequality and corruption. Capitalism is far from being toppled in the US, but its neoliberal era may be drawing to a close, Gary Gerstle, a professor of American history at the University of Cambridge, recently argued in The Guardian.

What, exactly, might replace it is unclear. But there are signs businesses will be expected to pick up a greater share of the costs in addressing problems.

One example would be what are called extended producer responsibility (EPR) laws, which make producers shoulder a significant share of the work or cost involved in managing their products once consumers are done with them. In the US, EPR laws already exist in a number of states to deal with items such as electronics, mattresses, and paint. Lately, bills focused on packaging have also begun appearing that would shift the financial burden of recycling from taxpayers back onto manufacturers—practically a rebuke of KAB’s campaigning decades ago. In July, Maine became the first state to require companies to cover the expenses of collecting and recycling plastic, cardboard, and other materials.

Fashion, meanwhile, is itself facing a raft of new regulations (paywall). Sweden looks set to introduce new EPR laws aimed at clothing and textile waste, while industry groups want Europe-wide EPR rules rather than a patchwork of regulations. The European Parliament is moving ahead with a far-reaching law that would require companies perform due diligence to identify and address human rights abuses in their supply chains. The US has issued a sweeping ban on imports of cotton products from Xinjiang in China over allegations the country is using Uyghur and other Muslim minorities as forced labor in its cotton industry.

Even if regulation could potentially be more effective than voluntary measures by corporations, it isn’t a panacea. Regulations can be cumbersome, as regulators themselves sometimes acknowledge. Some rules are difficult to enforce, and as Harrison pointed out, they don’t extend beyond a country’s borders. Government might also not want to impose stricter controls. The UK in 2019 rejected a proposal that would have forced fast-fashion retailers to take greater steps to remedy labor abuses, environmental damage, and excessive waste in their supply chains. In the US, the Biden administration faces hurdles in the courts too. Sustained change will likely require a mix of policy and corporate cooperation, with consumers also making some effort to show support through their purchases.

Businesses themselves may be coming around to the idea that they do, in fact, bear some social responsibilities. Since 1997, the Business Roundtable, a group of influential leaders in corporate America, had taken Friedman’s doctrine that corporations exist to serve their shareholders as gospel, enshrining it in its mission statement. In 2019, however, it updated that statement to assert that corporations exist to serve a range of stakeholders, including customers, employees, suppliers, and communities. Understandably, skeptics question whether they will follow through. But the revision itself is an indication of how demands on business are changing.

Bédat points out that the relationship between government, business, and consumers isn’t set in stone. The paradigm that dominated for decades wasn’t simply inevitable. It was the result of choices made by different stakeholders, based on ideas pushed by the Milton Friedmans of the world, which we adopted as the law of the universe. “It isn’t,” she says. “It’s just ideas that have gotten lodged in our brain.”