It’s official. Goldman has lost its trading mojo.

The investment bank’s bread-and-butter trading businesses, where it has generated the majority of the storied franchise’s profits, are hobbled for at least the next two years. That’s the picture that the high-profile Sanford Bernstein banking analyst Brad Hintz paints of the world’s most prominent investment bank in a recent research report. Hintz, who has historically been a booster of Goldman’s capacity to outmaneuver rivals, downgraded the investment bank to “market perform” due to concerns about its future performance over the coming years.

It’s hard to argue with Hintz’s assumptions. We’ve explored some of Goldman’s problems in past posts here, focusing on the bank’s dependence on fixed income, currencies, and commodities (FICC)–a segment that includes bond and foreign-exchange trading, and has been facing serious headwinds due to new regulation and a decline in risk-taking. Here’s how Hintz puts it in his research note:

It could take years for this hobble to come off: for the markets to reprice and for the Street to be able to pass through the cost of higher capital and lower leverage, for the cycle of ever more onerous CCAR exams and business prohibition on the part of the regulators to end, and for the competitive landscape of the capital markets to rationalize. For now we believe the stock is fairly priced, given the risks inherent in sales and trading and Goldman’s significant exposure to that business. Given these regulatory changes, along with the current difficult market conditions due to central bank monetary policies, we are downgrading Goldman Sachs to Market Perform.

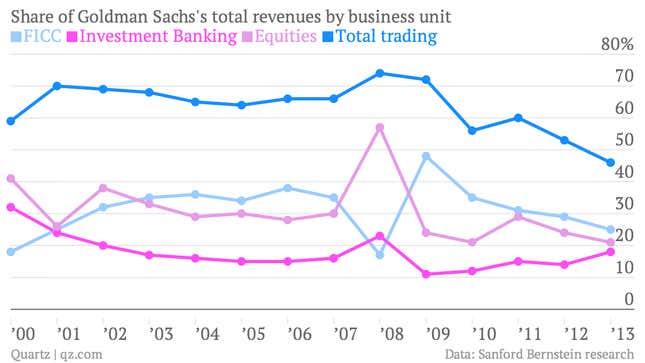

Hintz also highlights how Goldman’s FICC revenues reached a peak in 2009 of nearly $22 billion, which represented nearly half Goldman’s total revenues that year. Revenues in FICC were 25% of total revenues last year. Fixed income currency and commodities client services (as Goldman refers to it) represented 31 percent of Goldman’s total revenues in the first quarter of 2014 and its total trading(including equities) business was nearly half of revenues during the same period:

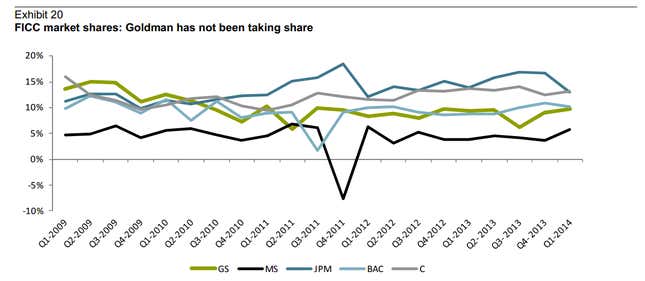

Investment banking, associated with the firm’s mergers and acquisitions advisory and initial public offerings businesses, has been on the uptick. But it’s still a smaller share, albeit growing, of Goldman’s returns. Another point that Hintz notes is that Goldman isn’t taking share in its core FICC market:

Meanwhile, Goldman has been letting its market share slip compared to rivals in equities trading:

Of course, Goldman isn’t completely alone here. The entire banking sector—including JPMorgan, Citigroup and Deutsche Bank—has been in a trading slump, as we’ve reported. But Goldman’s reliance on trading is part of what makes the bank so vulnerable, Hintz argues:

FICC was the largest contributor to profitability and now is in a situation where it seems to be structurally impeded. And in addition, the accommodative Fed policy of the past five years has led to low volatility and less trading. We don’t see an imminent change to this, at least over the next few years. M&A is in recovery mode, but it is a cyclical business and won’t be able to offset the sales and trading declines through all points in the cycle.

It’s not all bad news. Hintz notes that Goldman is still the best in breed of investment banks and if anyone can navigate this tough terrain, he predicts, it’s Goldman. But that might require a return to Goldman’s core M&A roots.