The Chinese government just announced that on May 1, it will launch an insurance program guaranteeing bank deposits, much like the US’s Federal Deposit Rate Insurance Corporation, which was instituted in 1933 to prevent bank runs.

Today’s statement hints that a long-delayed plan to free up the current cap on deposits may finally be nigh, a possibility China’s top central banker, Zhou Xiaochuan, recently alluded to. The insurance system is a prerequisite for interest rate liberalization, perhaps the most critical of the long menu of reforms promised by president Xi Jinping back in November of 2013.

Today’s announcement is somewhat surprising, given that it comes as the economy is looking unusually sickly; analysts estimate that first-quarter growth slowed to as little as 6.8%, below the government’s annual growth target. In the past, Chinese leaders’ focus on keeping the economy steady has forced Zhou to back-burner deposit rate liberalization, one of his pet reforms.

While the more interesting drama likely awaits deposit-rate liberalization, there’s a chance the insurance system’s launch itself could unleash a little havoc.

One big question is what happens to the deposits that aren’t guaranteed, as we recently explained. The insurance system will guarantee deposits of up to 500,000 yuan ($81,000). That suggests that about 99.6% of deposit accounts will be covered, according to Richard Xu, an analyst at Morgan Stanley.

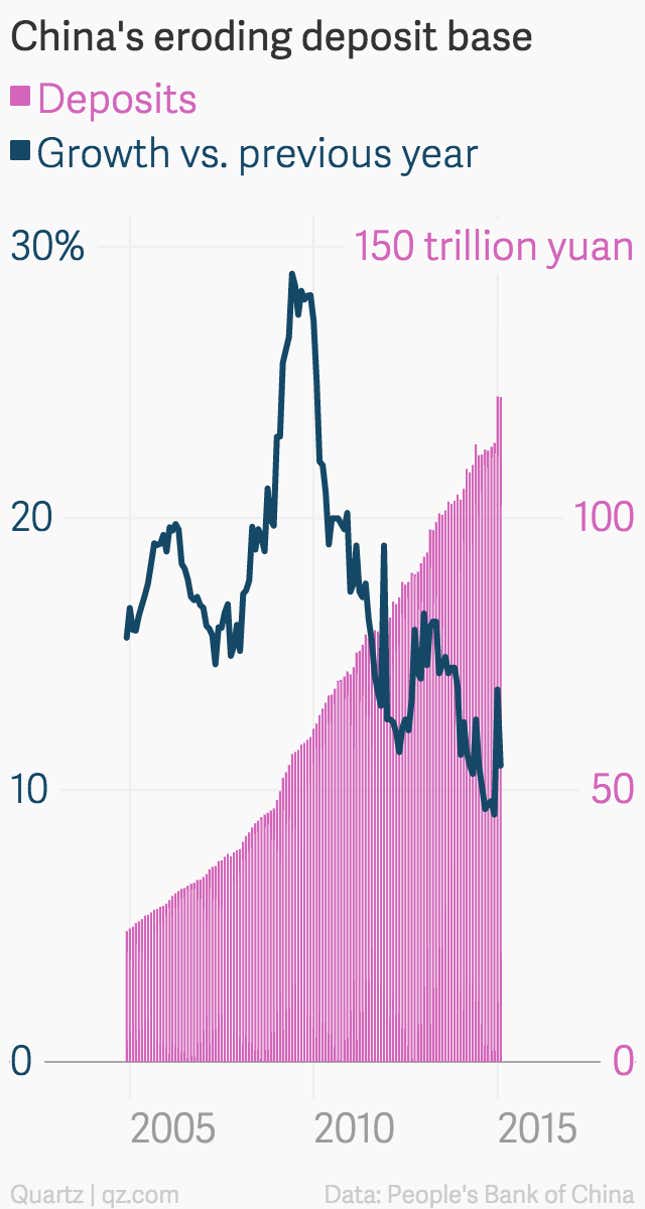

But thanks to China’s grossly uneven wealth distribution, the remaining 0.4% of accounts hold nearly half of the total value of all Chinese bank deposits, estimates Wei Yao, an economist at Société Générale. If, come May 1, some of the holders of those gigantic accounts decide to move their savings somewhere safer, it could drain cash from the system abruptly, throwing the banking system into tumult.

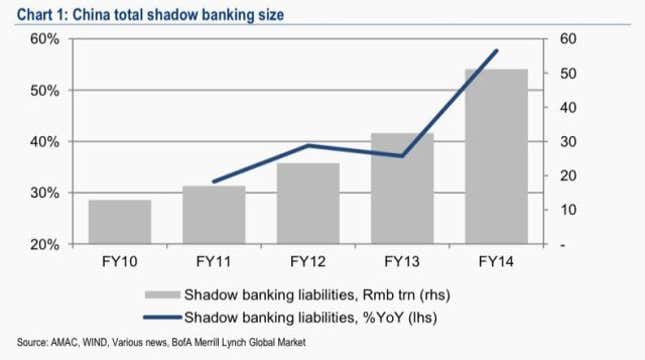

Another concern is that by spelling out what the government does guarantee, savers might stop investing in wealth management products—a major channel of shadow banking—the much higher yields of which have diverted a flood of savings away from bank deposits in recent years. So far, defaulted WMPs have been bailed out by a government entity. If investors read deposit insurance was a sign that will stop happening, a flight from WMPs to bank accounts could suddenly suck cash from the already vulnerable firms that rely on this shady lending.

As for what will happen when China scraps its deposit rate—which, again, Zhou says will happen this year—well, no one’s really sure.

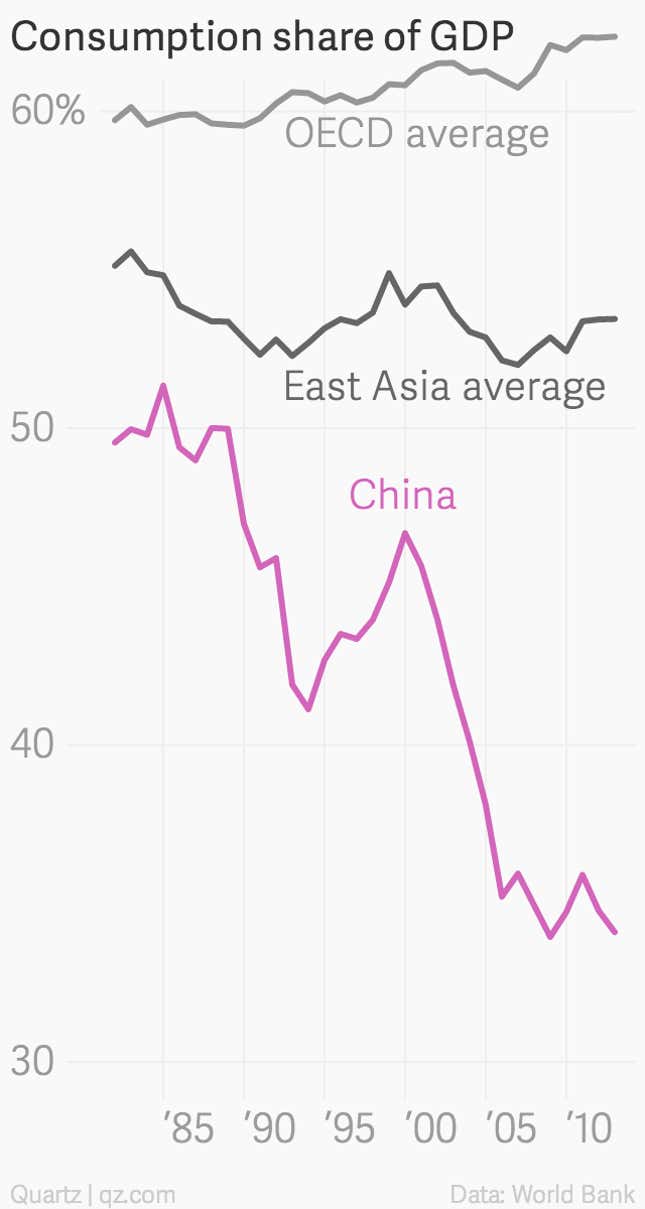

The government-rigged deposit rate has long been the linchpin of China’s economic model; by setting it artificially low—often lower than inflation—the government forces savers to subsidize borrowers, most of them profligate state-owned or -affiliated companies. The cost of this insta-growth policy has been household consumption: The fact that inflation eats into savings, meaning many actually lose money on their bank holdings, encourages savers to scrimp all the more. On the flip side, ultra-cheap borrowing has ballooned China’s corporate debt to 125% of GDP.

In theory, lifting the rate—encouraging banks to lend based on returns, not political priorities—will spur consumption by allowing savers to feel wealthier. That, in turn, will help China “rebalance,” as household spending offsets falling investment. What will happen in practice is another question. Capital Economics argues that the rate liberalization will have a muted effect, unless the government removes its ”implicit guarantee” of local governments and state-backed firms, probably by allowing some to fail. That’s bad for China’s debt pile, but good for short-term economic stability.

Whatever the case, letting the market determine bank-deposit rates (i.e. how much banks must pay savers to fund their lending) will likely ratchet up financial system stress. For one, it would drive up borrowing costs for companies and local governments—a potentially perilous move given that many of those are already struggling to manage their debt. It would also swallow up the profitable interest rate spread that banks currently enjoy.