For Quartz members—What’s measured gets treasured

Hi [%first_name | Quartz member%],

Hi [%first_name | Quartz member%],

We rely on data to run our economies, understand global events, and plan our futures. But it helps to have a healthy skepticism of the way data are compiled and interpreted. After all, human beings are behind all that collation and interpretation, and human beings come with baggage.

This week, we’re looking at how economists have struggled with a reliance on data devoid of context. But first: What do Somali livestock and India’s Taj Mahal have in common? They’re both major sources of revenue for their countries, which are taking massive hits due to coronavirus. Plus: Netflix is winning against HBO, spending is back to normal for poor Americans (but not rich ones), and there’s a case to be made for regulating Amazon like a railroad.

Your most-read story this week: Our definitely-not-fake letter from Bill Gates to Jeff Bezos about testifying before Congress. And the most relatable member award goes to whoever was reading The life-changing magic of overpriced candles. Go ahead and treat yourself.

Okay, open your spreadsheets and prepare your pivot tables.

How economists think about racism

Bill Spriggs hopes the Black Lives Matter protests will be a teachable moment. In a June open letter published by the Minneapolis Federal Reserve, the Howard University economist and National Bureau of Economic Research board member called on his field to reconsider its approach to studying racism.

In Spriggs’ view, economics has racism baked into it, and key to his argument is the way the field studies discrimination. (You can read the full details of Sprigg’s concerns here). Spriggs wants economists to spend less time studying—and sometimes justifying—the minutiae of racist behavior, and less time tackling narrow questions. Economists would be better off if the discipline accepted that racism is a pervasive part of American society, he says, and focused on learning the history of how it’s perpetuated.

For smarter ways to study racism, Spriggs points to the work of Ohio State economist Travon Logan, who has looked into how Black voting rights after the US Civil War led to improved public finances and concrete gains in Black literacy. He also commends the work of Jhacova Williams, an economist at the Economic Policy Institute. She has examined how the share of streets named after Confederate leaders in a city predicts differences in unemployment rates and earnings between Blacks and whites, even after accounting for educational attainment.

Spriggs wants economists to be more imaginative about what could change. As he points out, systems can be transformed. The power of governments can rise and fall. Institutions like slavery can be abolished.

“We’ve become so focused on marginal analysis, we’ve lost our ability to talk about systems,” he says. “We should ask, ‘How does the system work? How did we get these levels of inequality?’ But most economists don’t think about it that way, they assume the system. They assume they are in a racist society, and then go from there.”

What’s needed, in the minds of critics like Spriggs, are economists willing to look at racism and its impacts holistically, in the way that French economist Thomas Piketty has addressed inequality. It’s harder and messier work than, for example, measuring whether hiring managers express taste-based or statistical racism. But it can also have much more impact. —Dan Kopf, data editor

🗣️ We need to talk. Here at Quartz, we can never get enough feedback—which is why we’re keen to know what you think about your membership experience. To help us improve, please fill out this quick two-minute survey. And be honest. No hurt feelings, we promise.

Mind the gap

How do the issues highlighted by Spriggs play out in data collection? One example is in the economic gaps between Black and white Americans.

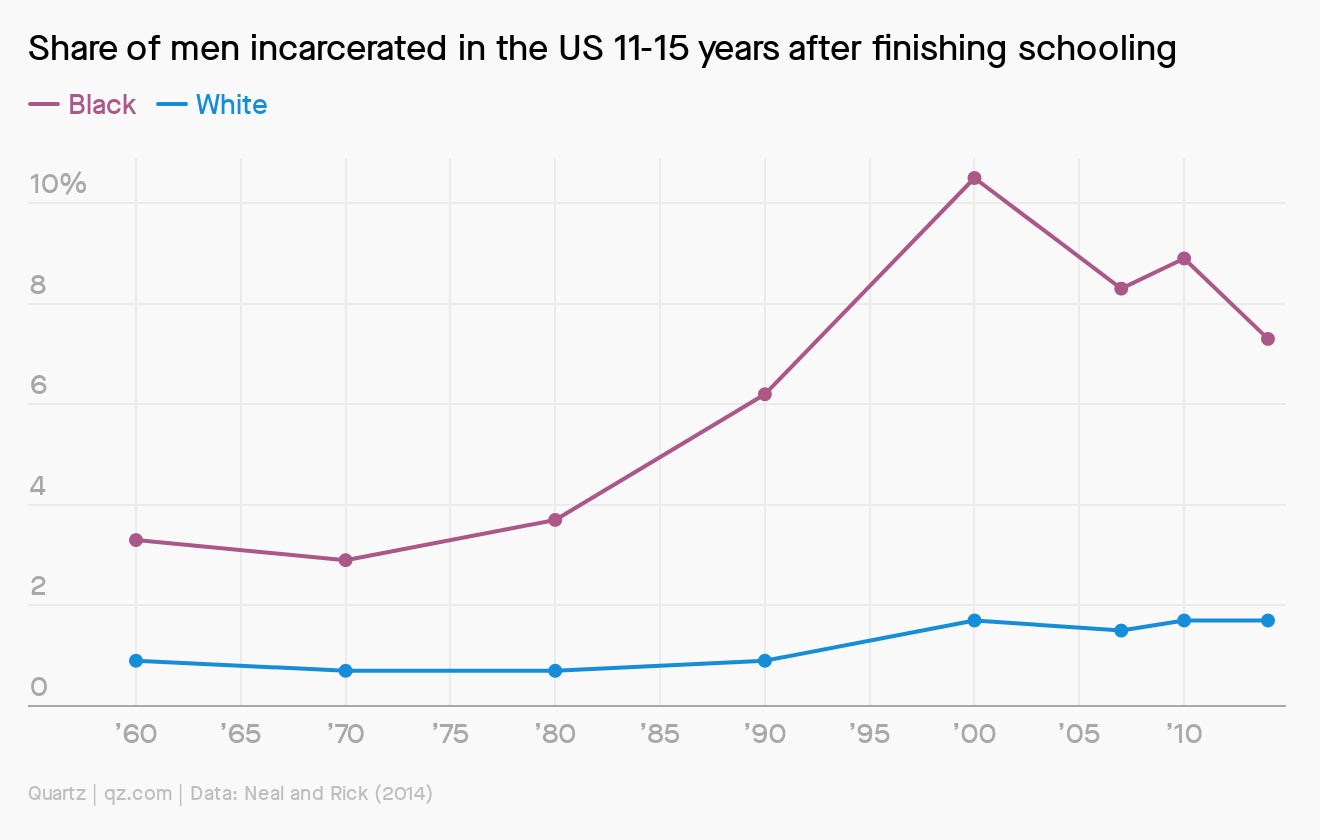

Many official US economic figures come from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The major surveys conducted by these agencies all exclude the more than 2 million Americans who are incarcerated. Since Black Americans are six times more likely to be incarcerated than whites and twice as likely as Hispanics, this has the effect of making it appear that African Americans are better off financially than in reality. (Read more here.)

“Whenever you see an employment rate for black men you know it’s BS,” says University of Chicago economist Derek Neal. “On any given day 7-8% of young black men are incarcerated and those people are not counted.”

Another example is in data collection for the 2020 US Census. As coronavirus outbreaks hit minority populations especially hard, experts and advocates worry that these traditionally undercounted populations will fare even worse. (Read more here.)

A naked economist walks into a room

No, seriously.

In March 2018, Victoria Bateman walked into the gala dinner at the annual conference of the Royal Economic Society in Brighton, the largest gathering of economists in the UK. Amid the formal business attire, Bateman, an economist and lecturer at the University of Cambridge, stood out: She was completely naked. Across her chest she had written “RES,” the society’s acronym, and across her stomach “PECT.” The message to her peers was a demand for respect for women and their place in economics.

This was not the beginning, nor would it be the end, of Bateman using her body to help deliver a message. “Women and women’s bodies are the elephant in the room in the economics profession,” she said. “This is what’s being ignored.”

In her book, The Sex Factor: How Women Made the West Rich, Bateman revisits economic history through feminist eyes, asserting that the missing piece to the growth puzzle lies in understanding the role women, their bodies, and freedoms played in creating prosperity. (Read more here.)

GDP why?

Last year Quartz spoke to an economist who is trying to shake up one of the most dominant stats in economics: gross domestic product. For years the field has tried to come up with a better way of measuring the economy.

One effort out of MIT, dubbed “GDP-B,” seeks to capture the numerical value of things that we don’t pay for but still have value, such as online maps, photos taken on smartphones, Wikipedia, and social media. We asked Erik Brynjolfsson, director of the MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy, why it’s so important that we change the way GDP is measured:

“There’s probably no more basic economic question than: How are we doing? Are we better off than we were last year? Is the economy doing better? Are children better off than their parents? Are the economic policies pointing us in the right direction? Are these innovations that companies are developing helping us at all? Those are really basic questions that GDP is used to answer, even though it isn’t quite the right tool.”

Essential reading

Even before the most recent Black Lives Matters protests, there was increasing pressure to rethink modern economics. Here’s a reading list to take you further down the rabbit hole:

- There is a growing movement to drag economics into the 21st century

- The dismal cost of economics’ lack of racial diversity

- The reinvention of economics after the crash

- The re-education of Economics 101

- A huge study proves that inequality isn’t just about class

Did you like today’s email? With this link and the code Memberreferral, you can recommend Quartz membership to a friend, so they too can enjoy emails like this one—plus a 40% discount on their first year. As always, we want to hear from you: feedback, questions, ideas, and your most hated statistical datapoint.

Thanks for reading! And best wishes for a measurably great end to your week,

Jackie Bischof

Kira Bindrim