Everything you should know about Japan’s oddly drama-filled elections

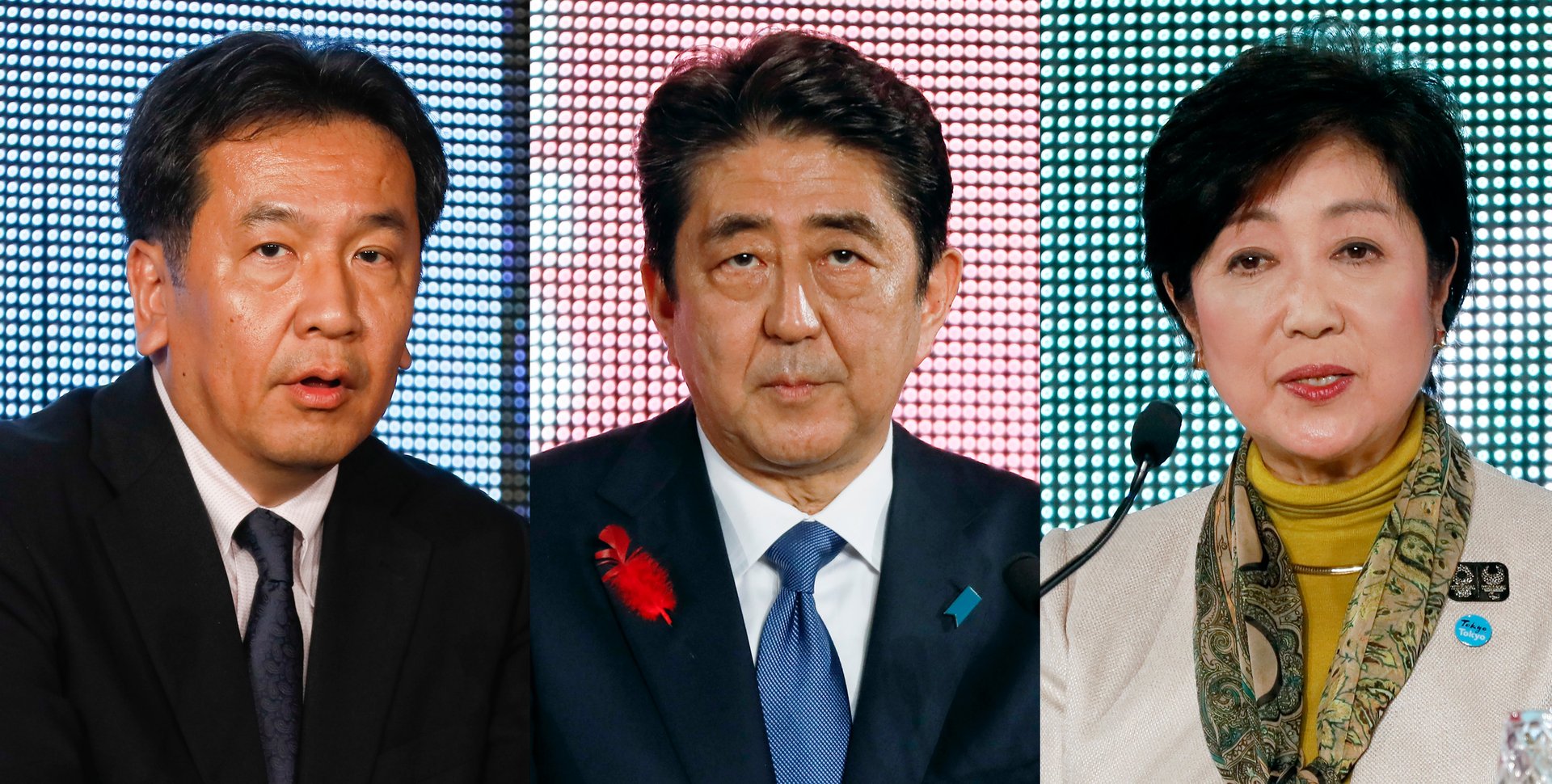

After an unusually drama-filled election campaign, Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe’s party looks set to win big in parliamentary elections on Sunday (Oct. 22).

After an unusually drama-filled election campaign, Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe’s party looks set to win big in parliamentary elections on Sunday (Oct. 22).

It’s been a campaign full of twists and turns, with parties forming and disbanding, and Abe’s grip on power looking set to face a real challenge for a brief moment. But the latest projections show that the status quo will very much continue on in Japan—and set Abe on course to become the longest-serving Japanese prime minister in the post-war period.

Why is there an election?

Abe announced a snap election last month and dissolved the lower house of the bicameral Japanese parliament, where his party the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) together with a coalition partner holds a two-thirds majority. An election wasn’t expected to take place until 2018.

Critics allege that the election is a ploy by Abe to further strengthen his power by kicking the opposition when it’s down, with the main opposition Democratic Party (DP) in complete shambles. Others say that Abe wanted to distract people’s attention from the scandals surrounding him this year by shifting the focus to other issues—Abe has himself justified the election as a way to confirm his mandate at a time when the country is facing a “national crisis,” chiefly because of the threat from North Korea.

So for a while people thought there was a chance Abe might not win, but now he’s almost definitely going to win?

Pretty much. When Abe first called the election, there seemed to be almost no real opposition to speak of, until Tokyo governor Yuriko Koike made things interesting by launching a new party that vowed to break the LDP’s power. Many were eager to see whether Koike, herself a former LDP member, could make a serious dent in the status quo. But it’s clear now that she’s unlikely to succeed—the latest polls basically say that voters haven’t flocked to her center-right alternative instead of the LDP as planned, and Abe will comfortably win a solid majority.

What happened to Koike?

Though she won local Tokyo metropolitan elections earlier this year in a landslide, voters found it hard to discern major differences between her party and the LDP on a national level. On foreign policy and security, she’s said that there’s no difference (paywall) between the two. The starkest difference between her Party of Hope and the LDP is over nuclear energy, as Koike has pledged a nuclear-free Japan (and a pollen-free one).

Many are also disgruntled that Koike effectively neutered the opposition even further. In response to her announcement of a party to challenge Abe in the election, the DP basically imploded, with the right-leaning rump of it effectively merging with the Party of Hope.

Koike herself also won’t be running in the election, and will stay in her day job at Tokyo governor—in fact, she won’t even be in Japan on Oct. 22, as she will leave for France the day before for a work trip (link in Japanese).

So there’s no opposition to speak of at all?

Not exactly. For a while, it looked like the Japanese Communist Party (JCP)—which despite its anachronistic sounding name still garners a serious following in Japan—was the only real left-leaning choice. But the chunk of the DP that didn’t go off with Koike quickly reorganized to form a new party called the Constitutional Democratic Party (CDP) under Yukio Edano, which according to some polls is ahead of the Party of Hope in support. Still, the party is too new to have enough of a track record to convince enough voters to switch over from the LDP.

Is it just me or are there are lot of acronyms?

Yes. Parties disbanding and splitting up and then re-emerging in new guises is commonplace in post-war Japan—except for the LDP, which has survived since the end of the war (though is itself divided into factions). It’s one of the reasons why a lot of the electorate is deeply apathetic about politics—indeed days before the election, many voters were still undecided. Turnout rates in recent elections keep hitting new post-war lows of just above 50%—the political editor of public broadcaster NHK warned that if then turnout level reaches 50%, the country will be in a “crisis of democracy” (link in Japanese).

What are the main issues?

The LDP is hammering the message that only it can protect Japan from North Korea and other geopolitical threats in the region. Abe is fashioning himself as a well-traveled statesman who is buddies with Donald Trump, as America basically underwrites Japan’s security through the post-war alliance. He also, ultimately, wants to revise the pacifist parts of Japan’s constitution that bar Japan’s armed forces from engaging in offensive operations, but it’s still a deeply divisive issue among the electorate.

On the economy, Abe wants to press ahead with a sales tax increase to fund things like childcare and education. The prime minister is boasting that his “Abenomics” economic reform blueprint is showing clear results—Japan’s economy is on a growth streak, there’s way more jobs than workers, and the stock market recently hit a 21-year high.

The Party of Hope and the CDP both want Japan to shift away from using nuclear power, with the meltdown of the Fukushima nuclear plant in 2011 still fresh in many voters’ minds. Since the earthquake that year, five reactors at three nuclear power stations have been restarted, and Abe has said he is committed to some degree of nuclear power in Japan.

So how does it actually work?

Voters receive two ballots, for single-seat constituencies and proportional representation (PR) ones. In the former, voters pick only one candidate and the person who wins the most votes gets elected. In PR seats, divided across 11 regions of Japan, voters choose from a list of parties, and parties win seats based on the proportion of votes they get.

There are 465 seats in the lower house, or House of Representatives, so parties running in the election will need to win over half the seats, or 233, to form a government. The LDP, in alliance with the small, Buddhist-linked Komeito, now have over two-thirds of the seats .

Voting begins (link in Japanese) at 7am and ends at 8pm; transportation is available to take elderly voters in remote locations to voting stations. However, early voting has already begun in earnest. The CDP is asking voters to vote before Sunday if possible as a typhoon is expected to hit Japan—voting turnout falls in the event of inclement weather conditions, it warns. Official results are unlikely before early Monday.

Why is this election important?

It could mark the start of the end of Japan’s pacifism, as enshrined in the constitution bestowed upon the country by the victorious US after the Second World War. With the exception of the CDP, the JCP, and the small Social Democratic Party, all the other major parties are supportive in some way of amending the constitution. That could end up alarming Japan’s long-standing foe China, and raise tensions in the region even further. More acrimony between Asia’s two biggest powers is not something the US wants.

But it’s still an issue that Abe will want to tread carefully on. “There’s a lot of discomfort towards Abe’s push toward a stronger military renaissance,” said Donna Weeks, a professor of political science at Tokyo’s Musashino University.

Japan’s post-war order won’t change overnight, but it’s already been slowly happening (paywall)—a big win for Abe could give him a bigger mandate than ever to press ahead with that change. But a win that isn’t convincing enough would signal that liberals in Japan (paywall) will live to see another day.