On Sunday (Nov. 11), Alibaba will mark the 10th edition of Singles’ Day, a one-day shopping event so big it eclipses both Black Friday and Cyber Monday, and leaves Amazon’s Prime Day trailing in the dust.

The story of how the shopping festival, also known as Double 11 for its date, grew from obscurity and just $7 million in sales to $25 billion last year, is also the story of the extraordinary growth of the e-commerce giant co-founded by Jack Ma in 1999—and a symbol of China’s rising consuming power.

Here’s a look back at how Ma and Alibaba turned Singles’ Day from a playful campus celebration into a phenomenon.

2009: A humble beginning

On Oct. 26, 2009, Jack Ma wrote an op-ed in the New York Times, ”Small is Beautiful,” extolling the possibilities of the internet economy.

“The headlines of the past year about storied global corporations all but collapsing in the wake of the global economic downturn were not signs of the times, but rather a foreshadowing that a long-awaited business revolution is actually beginning,” he wrote. Describing the rise of a new class of “netrepreneurs,” he added, “The entire Internet will be their marketplace, and the platform will be their office or shop.”

These were surprisingly cheerful words in the midst of the global financial recession, when China, like other economies, was struggling to revive its economy. Ma’s op-ed came just two weeks before the first Singles’ Day, which company was hoping would get more merchants to embrace its new brand-to-consumer platform Taobao Mall (later rebranded to TMall to avoid confusion with Taobao, its consumer-to-consumer marketplace).

Within Alibaba, the company credits the creation of Singles’ Day to CEO Daniel Zhang, who will take over as chairman from Ma next year.

“Many people ask me how we came up with this idea, and my honest answer is… survival,” said Zhang in a corporate Q&A last year. “At that time, Taobao Mall was a young business and few people knew what it was.”

Zhang, who had become the head of Taobao Mall two years earlier, sensed a business opportunity (link in Chinese) in the month of November, fairly quiet for retail sales since it fell after China’s Golden Week holiday, when people spend money traveling, and before Christmas shopping.

According to TMall World general manager Elaine Hu, then a member of the marketing team that came up with Singles Day, inspiration hit when a team member was snacking on chocolate-covered Pocky sticks, and someone mentioned the snack was known as guang gun, or “bare branches” food in South Korea. In China, “bare branches” is a reference to men who remain perpetually single, a more noticeable phenomenon now due to the skewed sex ratios in of the 40-year-old one-child policy that was abandoned two years ago.

In fact, Pocky originated in Japan, but it’s similar to Pepero, gifted on 11/11 among friends in Korea. China too was already marking that day in a small way: In 1993 a group of university students at Nanjing University decided to start celebrating being single on 11/11, since the number 1 stands for aloneness while the date looks like four lone sticks, or branches. The Alibaba team liked the simplicity of the date, and that was that.

Alibaba promoted the festival with the slogan, “Even if you don’t have a boyfriend or girlfriend, you can at least shop like crazy.” (就算没有男女朋友,至少我们可以疯狂购物). By emphasizing that singles—often shamed over their status—should treat themselves, Alibaba created a kind of party feeling, wrote Zhang Hailan, a folklore researcher with East China Normal University (link in Chinese) in 2015.

The thinking was simple—offer a 50% discount and free deliveries to attract consumers, says Hu, but it was hard to convince merchants to believe in the idea, or the unconventional midnight shopping start time. Many merchants dropped out at the very last minute, leaving only 27 participating in the shopping festival, Hu recalled. Yet just a few hours into the event, Alibaba says it had to wake up merchants to ask them for more supplies, after goods quickly sold out.

Danish fashion brand Bestsellers’ China affiliate, which sells clothes under the Jack & Jones line and three other brands, was part of that first Singles Day. The Chinese fashion firm’s sales volume reached 5 million yuan ($720,000), or 10% of the day’s total sales of $7 million (link in Chinese). That was two months worth of regular sales in China, according to Gina Sun, vice president of Bestsellers Fashion Group China.

2010: More than $100 million

In 2010, Taobao Mall hosted an average of more than 20,000 yuan ($3,000) of sales every second, and reached total sales transactions of 936 million yuan ($135 million). China also got the first inklings that the annual shopping event would also be an annual delivery nightmare (silver lining: new billionaires).

Many people had to wait a month or even several months for their packages after the sale back then, while it usually only took one to two days, according to a 2015 China’s state media People’s Daily (link in Chinese): “It’s from that year that the phenomenon of demand exceeding supply began… there were even cases where merchants’ printers broke because there were too many printings. Seeing such an unexpected scenario, many companies even moved staffers from the accounting, administration departments to the e-commerce sector, but even that was barely enough.”

Singles’ Day quickly inspired competing festivals. In 2010, JD.com, now China’s second-biggest e-commerce site, started the 618 (June 18) shopping day.

2011: Bye-bye Singles’ Day

Just two years in, the phrase “Singles’ Day” began disappearing from Alibaba’s market campaigns around the event, noted Chinese writer Wang Lu in Youth Studies, a magazine from the state-backed think tank China’s Academy of Social Sciences (p. 8). In the following years, Double 11 is no longer guang gun jie, but referred to mainly in terms of internet shopping, he wrote.

The sales volume in 2010 showed Alibaba that the event had mass appeal, which is why it decided to broaden its marketing of Double 11 as a shopping event for everyone, said Tmall World’s Hu. Still, many discounts by retailers and ads continued to be tailored to singles.

In 2011, Taobao Mall and Taobao (link in Chinese) together brought in 5.2 billion yuan ($750 million) in sales. In the same year, Alibaba also rolled out another annual shopping event—known as Double 12 (link in Chinese). Held on Dec. 12, it’s meant to help businesses deal with Double 11 stockpiles that didn’t sell out during the first shopping event. The first Double 12 brought in around 4.4 billion yuan ($630 million) in sales.

2012: Sales surpass Cyber Monday

Taobao Mall changed its name to Tmall in the fourth year of the annual shopping event, when sales figures for the first time surpassed Cyber Monday. That was a shopping day the US National Retail Federation named in 2005, after observing that since consumers didn’t have high-speed internet access at home, the Monday following Thanksgiving would see a spike in online shopping.

It’s also the year that multiple online shopping platforms (link in Chinese) outside Alibaba jumped in to make use of the annual shopping day. Dangdang.com, an online shopping site for books, Amazon China, and electronic devices chain Suning all rolled out online promotions under the Double 11 banner.

2013: The dawn of a mobile shopping era

By this point, people can nearly buy anything from Taobao and Tmall—from a pillow boyfriend to a 13.33-carat diamond that cost $3.37 million—and they did. It took the two site around nine hours to exceed what Cyber Monday had achieved in a day’s sales in 2012; for the full day, they brought in $5.8 billion.

In the first hour of the shopping event, Alibaba said around 24% of orders came through smartphones. China at that time was already the world’s largest smartphone market, and the shift to smartphone shopping fueled the rise of China’s most well-known mobile payment app, Alipay, which has 520 million users worldwide.

The same year, an Alibaba-led consortium set up Cainiao Network, a logistics platform that aimed to do for delivery what Alibaba’s other platforms were doing for sellers and shoppers.

2014: The year of the IPO

Alibaba, which by then had equivalents to all sorts of US tech services, listed in the US in September 2014—raising $25 billion, it was the biggest IPO ever. That came two months before its 2014 shopping event, which was naturally especially closely watched by investors. Zhang, then chief operating officer of Alibaba, described the preparations as a “war” to Quartz back then. “A virtual war but no enemy,” Zhang said.

An increasingly important tool was the huge amount of data the event was gathering—people’s shopping habits, time spent, locations. For example, after analyzing purchase data from Taobao, the company concluded that women who bought larger bra sizes also tended to spend more.

That year, Alibaba branded the day as a “global shopping party,” reflecting the boom in overseas shopping by the growing numbers of Chinese tourists, and took in a total of $9.3 billion in sales.

2015: The stars are out

While China saw an overall decline in high-end shopping in 2015 due to China’s political clampdown on corruption and the stock market’s troubled performance, that didn’t stop Alibaba from beating its past record—or throwing a star-studded countdown party that was broadcast live on national TV.

The star-filled gala was held at the National Aquatic Center, which was built for the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Ma shook hands with Daniel Craig at the kickoff festivities; together, they unveiled 11 winners who could buy cars from the luxury vehicle brand Cadillac for one yuan. It’s been a tradition since then—Alibaba invited other high-profile stars like Kobe Bryant, David Beckham and his wife Victoria Beckham, and Nicole Kidman in the following years.

The 24-hour shopping marathon brought in some $14.3 billion, more than the total $13.5 billion from Black Friday and Cyber Monday sales in the same year. The “hand-chopping” meme took off—a reference to the drastic measures people feel they require to stop their frenzied shopping.

2016: High-tech shopping and flashy cars

Alibaba incorporated more technology to help customers shop overseas in 2016. For example, the firm worked with US department store chain Macy’s to develop a virtual-reality headset to allow Chinese customers to sit at home and look for goods at a Macy’s store.

During the 24-hour shopping gala, Alibaba also sold more than 100,000 vehicles, equivalent to a month’s sales from 1,000 typical Chinese dealerships, according to data from Alibaba.

Alibaba saw $17.3 billion of total sales generated in the shopping gala of 2016.

That year also saw an unprecedented amount of packaging, a huge source of pressure on the environment, according to a study by the non-profit environmental organization Greenpeace. The nonprofit has urged Alibaba to set up incentives to encourage recycling packaging cardboard.

2017: Crossing $25 billion, serving the middle class

Liu Peng, the general manager of Tmall’s international business sector, said that the sector has served more than half a billion members of China’s new middle class, judging by the most popular items over the years. These include diapers in 2013, steam eye masks in 2014, foam latex pillows in 2015, electric facial cleaners in 2016, and window-wiping robots and cat food in 2017, the latter a sign of the middle class’s growing desire to have pets.

Other popular items related to China’s aggressive push of a two-child policy, which replaced the one-child policy in 2015. In 2017, searches for “double strollers” increased by 83% (link in Chinese) on Tmall during the shopping event. On the same platform, the number of users that purchased the same children’s item in a pair also increased by 18%.

Alibaba closed the shopping marathon with $25.3 billion—with 90% of those sales from mobile. Vitamins, diapers, and baby formula—a perennial favorite on Singles’ Day due to a contaminated milk scandal that left lingering distrust of local formula—were popular items from abroad. Russia was the biggest source of overseas customers.

2018: Uncertainty

The ongoing trade war with the US, which could dampen shopping enthusiasm, hangs over the 10th edition of Double 11.

Ma described the trade war as “the most stupid thing in this world” this week, following his remarks earlier this year warning a trade war could last decades. Although most of Alibaba’s revenue comes from domestic commerce, the trade tariffs and economic uncertainty from China’s slowing economy have forced the company to cut its full-year revenue forecast by 4% to 6% in a call with analysts in early November.

On the call, Alibaba’s Zhang said there could be impact on purchases of big-ticket items, and also said the company will delay efforts to earn more revenue from the businesses that sell on its platforms. Alibaba’s e-commerce revenues come from fees it charges business, commissions, and advertising.

It’s unclear how this year’s sales numbers will be affected. People still seem to be enthusiastic about the event with articles about shopping strategies circulating widely on social media this month, and pre-orders beginning last month.

Elements of Alibaba’s reconfiguration of its business, which includes expansion into offline stores (paywall) and services, such as by taking ownership of food delivery service Ele.me, will be visible this year. Consumers glued to their phones or computers can this year order food and drink from within the Alibaba universe, an option that wasn’t possible before.

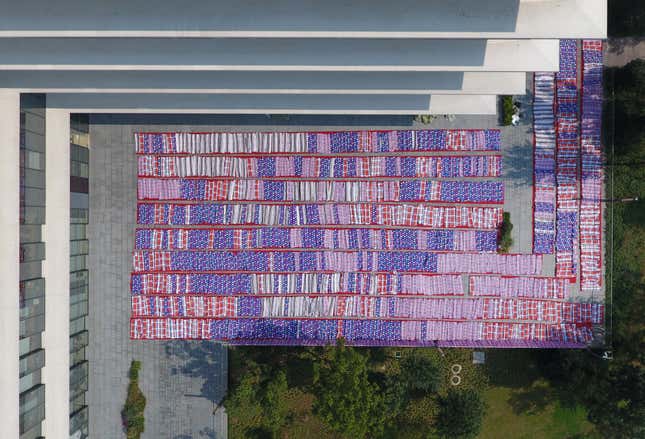

Alibaba is fully prepared: in its Hangzhou headquarters, staff are airing out more than 20,000 quilts (link in Chinese) for workers who will be staying at the office for the shopping marathon.

Correction, Nov. 9: Elaine Hu is Tmall World general manager. This article earlier identified her as a business development manager at Tmall Global.