Hi [%first_name | Quartz member%],

Here’s a quote you can apply to just about anything right now: “Well, I wish we had handled that differently.”

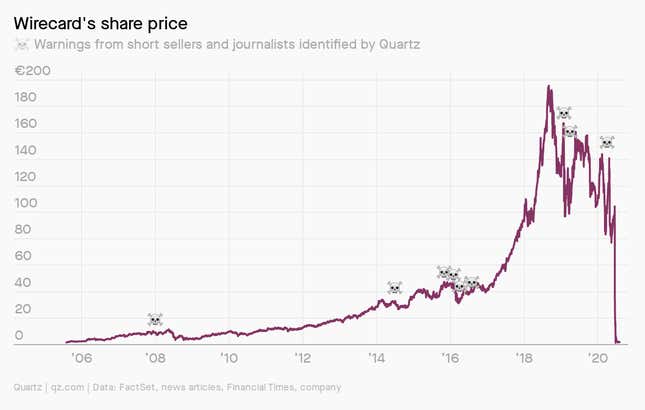

That’s what auditors, German regulators, and investors are saying after payment company Wirecard melted down this summer in one of the all-time great financial scandals. It’s got a little of everything: years of red flags that went ignored, government watchdogs who defended the company, and billions of dollars that may not have existed. Today we’re unpacking the whole debacle, and the short-selling canaries in the coal mine.

But first, a recap: Africa’s largest retailer pulled out of the continent’s largest economy, Zoom found a way to outsource its censorship in China, and Amazon is making more money during the pandemic than it does over Christmas. Professional basketball came back and it was weird, as are everyone’s conversations these days. Who owns TikTok now? Can we trust the US presidential polls? Will men’s suits survive Covid-19? Only time will tell.

Your most-read story this week: Without an office, what defines the workplace? And shout-out to the member reading a true Quartz classic: Why are we still calling them phones?

Okay, grab your calculator and turn on the oven. We’re cooking some books.

Don’t sleep on short sellers

Let’s start with a billion-dollar question: Why do mega-financial-frauds keep happening? 2008 brought us the discovery of Bernard Madoff’s Ponzi scheme, and 2001 gave us Enron. This year, we got Wirecard.

Except Wirecard’s woes didn’t leak out this year. Multiple short sellers had been ringing the alarm bell for a decade or so. And while government authorities seem to have ignored those short sellers (or even attacked them), the Financial Times didn’t. The British newspaper listened to the naysayers and followed up on the whistleblower accounts. It has since been vindicated, but in the meantime was sued by Wirecard and investigated by German regulators, who also stripped short sellers of their ability to bet against Wirecard in 2019.

The episode underscores the value of high-quality journalism (thank you, Quartz members) as well as short-selling activists who seek to expose corporate frauds. These investors make money on their investigations by betting against—short selling—their targets in the stock market, or by selling their research to investors.

Short sellers are occasionally heroes in the media, but they’re hated pretty much everywhere else. Napoleon reportedly labeled them “enemies of the state,” while the former head of the New York Stock Exchange said they were “icky” and un-American. Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey recently warned short sellers to “stop” betting on stocks to fall, while governments from Belgium to Spain curbed the practice this year amid market mayhem stemming from the pandemic.

It takes a thick skin to be a short seller; pretty much the entire financial system is geared to want stocks to go up. That includes corporate management, investors, stock exchanges, and politicians, as well as investment bankers, consultants, and some media types. But this is also why short sellers are helpful. They are often contrarian by nature and have an interest in seeing things differently—a diversity of ideas that the evidence shows can help detect frauds and scams.

What he said

“There’s a lot of what I do that is somewhat similar to journalism. The more people are anesthetized to risk—which was definitely the case coming into Covid and I think we’re really back to that in spades—the more that’s the case, the more selective you have to be and the better you have to be at explaining to investors why it matters to them.” —Carson Block, one of the world’s best known short sellers

What happened at Wirecard?

Wirecard has roots going back to 1999, when it started out as a payment processor helping websites collect digital payments from customers. In the early days, its main business was handling transactions for porn and gambling sites.

Markus Braun, an Austrian computer scientist and former consultant, took over in 2002. Three years later the company was listed on the Frankfurt stock exchange by way of a reverse IPO (it acquired a listed company instead of going through a regular public offering—potentially avoiding an important opportunity for investors to pore over its books). Not long after, Wirecard bought a bank, which allowed it to issue credit cards.

In the next decade, Wirecard raised hundreds of millions of dollars from investors and used the money to go on an acquisition spree, snapping up payment companies to widen its network. Mark Hiley, a founding partner of research firm The Analyst, told the New York Times that these deals were odd: They were small businesses that didn’t make much money. Yet Wirecard was spending heavily on them, and then reporting almost immediate profitability.

As questions grew, so did Wirecard’s profile. By 2018 it had joined Germany’s DAX stock index, pushing out 150-year-old Commerzbank. In April 2019, it got a €900 million investment from Softbank, the Japanese conglomerate. But scrutiny from short sellers and from the Financial Times persisted, even as financiers and journalists were targeted by lawsuits and private investigators. Wirecard finally bent to the pressure to appoint KPMG for a special audit, after EY had given it a clean bill of financial health for years.

KPMG’s bombshell struck in April. The firm said it couldn’t verify most of the arrangements supporting Wirecard’s profits in recent years, and raised questions about €1 billion worth of cash balances. By June the fintech was completely unraveling and finally admitted the potential size of an immense fraud—that $2 billion of cash on its balance sheet likely wasn’t there. Before the month ended, Braun was arrested and the company had filed for insolvency.

A brief history of red flags

2005: Wirecard is created through a reverse IPO.

2008: Ennismore Fund Management bets against Wirecard, according to the FT.

June 2008: Wirecard says it has been the victim of short-selling attacks.

July 2014: Mark Hiley of The Analyst raises red flags about Wirecard.

November 2015: J Capital Research raises questions about Wirecard’s Asia business, according to FT Alphaville.

February 2016: Zatarra, an anonymous group, publishes a critical research report about Wirecard practices.

February 2016: John Hempton of Bronte Capital publishes a blog post saying he has been shorting Wirecard for years.

April 2016: The FT reports that John Fichthorn of Dialectic Capital is shorting Wirecard after reviewing a suspicious acquisition in India.

January 2019: The FT publishes a Singapore whistleblower’s account of suspicious transactions at Wirecard.

February 2019: Singapore police raid Wirecard’s office after the FT’s report of fraud.

February 2019: BaFin, the financial regulatory authority in Germany, bans short selling of Wirecard stock.

April 2019: BaFin files a criminal complaint against the FT and several short sellers.

April 2019: The FT reports on a whistleblower claim that most Wirecard profit came from opaque partners.

April 2020: KPMG’s bombshell hits: It can’t confirm years of important Wirecard revenue.

April 2020: TCI Fund Management calls for the ouster of Wirecard’s CEO.

June 2020: Wirecard says it plans to file for insolvency.

What’s in a name

There are a few go-to themes when it comes to naming your financial institution. Big asset managers like something heavy- and hard-sounding—like BlackRock or Blackstone. (Or Northern Rock, which suffered a bank run during the financial crisis.) Greek gods are popular with hedge funds. Banks used to glom on to sovereign-sounding names—Bank of America, US Bank, or (my hometown favorite) First National Bank.

For short sellers? A possible penchant for superheroes. See: Gotham City Research, Wolfpack Research, and ShadowFall Research. We asked the newsroom for some similar suggestions and got back a few good ones: Hulk Associates, Captain Capital America, and Darkwing Duck Ltd. among them. But we suspect you can do better.

Essential reading

- The source material: Inside Wirecard: The Financial Times’s multi-year series of stories.

- The backstory: Bloomberg’s QuickTake on the history of short selling and how it works.

- The landscape: Quartz’s guide to the biggest private fintech companies.

- The sleepy watchdog: A Wall Street Journal spotlight on Wirecard’s auditor, EY.

- The ironic preface: EY was ready to give Wirecard a clean bill of health just before it collapsed.

- The ironic outcome: Short sellers were vindicated on Wirecard, but still lost millions of dollars.

- Just because: The world’s best known short seller says Tesla traders are feeding on testosterone.

Did you like today’s email? Are there other big stories or complicated topics you’d love Quartz to unpack? Send them our way, along with any feedback, questions, or stocks you’d like to short.

Thanks for reading! And best wishes for an above-board end to your week,

John Detrixhe

Senior reporter, future of finance

Kira Bindrim

Executive editor