India’s top mobile browser. Hong Kong’s Uber for logistics. China’s second-largest bike-sharing service.

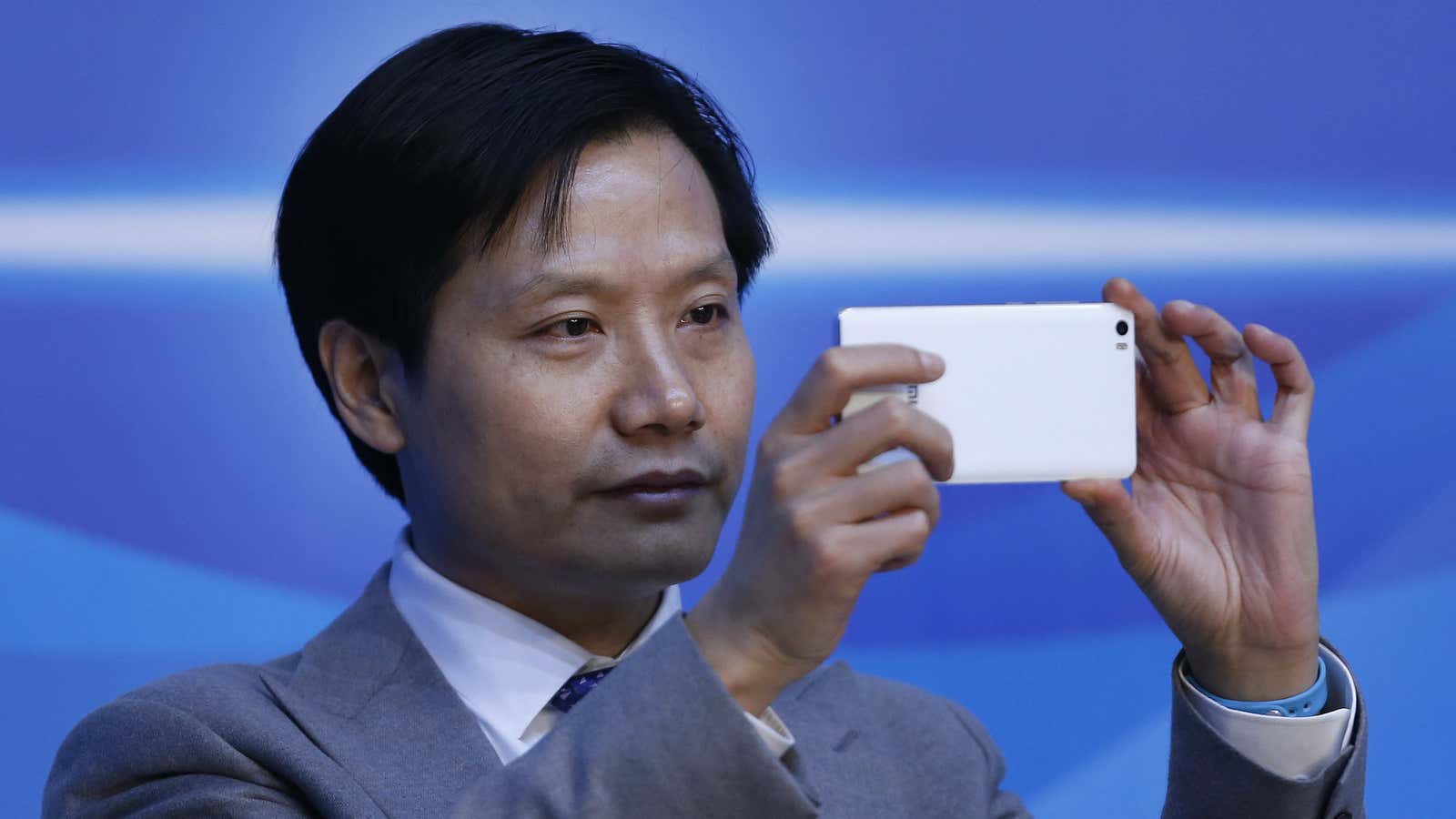

Those are just some of the companies backed by Chinese entrepreneur Lei Jun. Globally, Lei is known as the founder of smartphone maker Xiaomi, which will list shares on the open market next week as part of its IPO. But within China’s tech industry, he’s known for more than shilling glass slabs. He’s one of the country’s most prolific tech investors, holding stakes in hundreds of companies across different sectors. The sprawling reach of his empire makes Lei a giant of venture capital in China, not unlike Masayoshi Son of Japan’s SoftBank.

The method to the madness

Lei invests primarily through three channels: Xiaomi, his VC firm Shunwei Capital, and angel investing. As of January, Shunwei has invested in 270 companies, Xiaomi in 157, and Lei himself in 33, according to a report (link in Chinese) from news site iHeima and research firm ITJuzi.

Speaking at an event in Tianjin in 2016, Lei said that he started investing around 2007 (link in Chinese). After stepping down as CEO of software maker Kingsoft, he had no immediate business plans and realized that the country’s tech industry lacked good sources of funding. “If you wanted to start a business, who would give you 1 million yuan, 2 million yuan? Executives would say go to the bank and get a loan.”

Parsing through the list of firms Lei has funded reveals no grand, unifying investment theme. Lei himself has said that he invests in people (link in Chinese) rather than ideas. But when viewed broadly, Lei’s most important deals fall into three categories.

The utilities companies

Lei holds stakes in two companies that are little-known in most parts of the world and make rather boring software—but are nevertheless quite large.

Lei currently serves as the chairman of Kingsoft, a Chinese maker of Microsoft Office-esque software and cloud services that’s valued at HK$28.3 billion (about $4.6 billion). In 2015, Xiaomi purchased a 3% stake in Kingsoft, which in turn raised Lei’s stake in the company to 29.9% (paywall).

Kingsoft, meanwhile, is a major shareholder in Cheetah Mobile, a maker of simple utility apps (flashlights, battery savers) that’s currently valued at $1.4 billion. Lei once served as the chairman of Cheetah Mobile but stepped down in March, though he retains a small personal stake in the company in addition to his stake through Kingsoft.

One of Lei’s most successful investments as an angel investor went into a seemingly ordinary utility app. In 2007, he purchased a 20% stake in mobile browser maker UCWeb for about $4 million (link in Chinese). The company was eventually purchased by Alibaba for roughly $4 billion, and its app is now the most popular smartphone browser in China (link in Chinese) and in India.

Xiaomi’s hardware ecosystem

While Xiaomi is best known as a smartphone maker, it also sells other internet-connected products, among them scales, wristbands, and air filters. Most of these “smart” devices are made not by Xiaomi but by separate companies that Xiaomi invests in—and then helps by selling their products on its website and in its brick-and-mortar stores. Some of the gadgets carry the Xiaomi brand, others the partner’s. According to Xiaomi’s prospectus, the company has invested in over 90 such companies (pdf, p. 4).

Several of these firms have enjoyed booming sales thanks in part to their association with Xiaomi. Huami, which makes Xiaomi’s smart wristband, ranked as the world’s second top-selling wristband company last year and IPO’d in New York in February. Ninebot, which makes scooters and hoverboards, has had some success in the US thanks to deals it formed with US-based scooter startups.

Lei also drew attention in 2014 when Xiaomi, then just four years old, announced it would invest in Midea, a Chinese maker of air conditioners and kitchen appliances founded in 1968. The bet paid off—about three years after the deal closed, the value of Xiaomi’s stake increased more than 200% (paywall).

Consumer internet

Through both Xiaomi and Shunwei, Lei has invested in hundreds of startups at the forefront of China’s internet boom. Some have become major players in the country’s tech industry. Among them are ByteDance, which makes the popular news aggregation app Toutiao; iQiyi, a Netflix-like streaming site that recently went public; and Kwai, a live-streaming app known for lowbrow content (paywall).

Other noteworthy investments include Lalamove, an on-demand delivery service that originated in Hong Kong; Dianping, a Yelp-esque listings site that later merged with rival Meituan; and Ofo, one of China’s leading bike-sharing companies.

There are hundreds more companies Lei has funded that the average Chinese consumer has likely never heard of, including WeChat self-help account Luoji Siwei, millennial co-living space operator You+, and Alibaba-backed electric-vehicle maker Xiaopeng Motors. Shunwei has even funded a diaper company (link in Chinese).

Lei has admitted that successful investing involves lots of luck. “Angel investing is a little like the lottery—you put down 1 million, 2 million and maybe get one 1,000- or 10,000-fold return, but most capital never comes back,” he once said (link in Chinese). “Overseas, Google and Facebook have nabbed 1,000-fold returns—and actually, I’ve nabbed 1,000-fold returns too.”