Uber’s stunning journey to a $90 billion IPO changed transportation forever

Uber redefined how we think about transportation. The original Uber concept—a private ride, summoned by tapping an app on your smartphone—was so simple and universally appealing that it upended the traditional cab industry practically overnight.

Uber redefined how we think about transportation. The original Uber concept—a private ride, summoned by tapping an app on your smartphone—was so simple and universally appealing that it upended the traditional cab industry practically overnight.

What Uber is today is tougher to define. It’s a household name and an app in everyone’s pocket. It provides rides and delivers food. It’s a massive employer, although Uber believes its workers aren’t employees, of the people who give those rides and deliver that food. It’s dabbling in flying cars and racing to develop ones that drive themselves.

On April 26, Uber set the terms for its widely anticipated initial public offering. The company seeks a valuation of up to $91.5 billion, less than a previously rumored $120 billion target but still big enough to make Uber’s IPO the largest in the US since Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba debuted in 2014. Uber plans to sell 180 million shares at $44 to $50 per share, raising up to $9 billion. Existing Uber investors are expected to sell another 27 million shares for as much as $1.35 billion.

As Uber prepares to list its shares on the New York Stock Exchange, under the trading symbol UBER, it’s hard to believe the ride-hail service didn’t even exist 10 years ago. Uber’s journey from scrappy startup to $90 billion company wasn’t long, in the grand scheme of things, but it beat some long odds.

In the beginning

Company lore has it that the idea for Uber was born on a snowy day in 2008 in Paris, when co-founders Travis Kalanick and Garrett Camp couldn’t get a cab. A 2014 profile of Kalanick in Business Insider told a different story: that Camp started thinking about how to create a cheaper private car service after spending $800 to hire a private driver for New Year’s in the late 2000s.

Kalanick, Camp, and a few other friends dreamt up UberCab in 2009 in San Francisco. The app officially launched in July 2010 when UberCab connected its first rider to a black town car for a ride in San Francisco. A few months later, in a storyline that would repeat itself many times over Uber’s life, the city ordered it to cease and desist.

Letters from the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency and the California Public Utilities Commission ordered UberCab to immediately halt all ads and operations as a for-hire ride service without proper permitting. “The name UberCab indicates that you are a taxicab company or affiliated with a taxicab company,” the local transit authority wrote on Oct. 20, 2010. “However, as there are no taxis in your fleet, we demand that your company, its affiliates, and any other entity to cease calling itself UberCab.”

Uber didn’t blink. “UberCab is a first to market, cutting edge transportation technology and it must be recognized that the regulations from both city and state regulatory bodies have not been written with these innovations in mind,” Ryan Graves, the company’s first CEO, wrote in a blog post that month. The company never paused service, but a couple days later, in a small concession to regulators, it dropped “Cab” from its name. From then on, it was just Uber.

“An asshole named Taxi”

In late 2010, Kalanick took the CEO reins from Graves and implemented a growth-at-all-costs mantra. Uber’s next few years were ones of feverish expansion.

To hasten growth, Uber established local operations teams and gave them carte blanche over their territories. The messy, decentralized strategy led to frequent blunders. An Uber manager in Arizona, deactivated a driver in Albuquerque, New Mexico, who tweeted an article that criticized Uber. The Uber team in New York City ordered and canceled thousands of rides from competitors in an effort to steal their drivers and stymie their service. An ad campaign in Lyon, France, promised to pair Uber riders with “hot chick” drivers.

Uber also displayed a brash disregard for personal privacy. In November 2014, the company’s top New York executive used an internal company tool called “God View” to track a reporter’s location. That same month, another top company executive threatened to dig up dirt on critical journalists. All those incidents and blunders gave Uber a bad image. But that didn’t impede the popularity of its service. Being able to order, take, and pay for a private ride from your phone was just too good.

By 2014, Uber was in 100 cities. It also had a local competitor, Lyft, founded in San Francisco in June 2012. But the company’s true enemy, as Kalanick put it, was “an asshole named Taxi.”

Taxi companies hated Uber as much as consumers loved it. In many cities, taxi operators essentially had local monopolies on ground transportation. Not just anyone could be drive a cab: You typically needed the proper permit, car, and meter. Some cities capped the total number of drivers allowed on their streets. In New York City, home to the famous yellow cab, a pair of permits known as taxi medallions sold for $1 million apiece in 2011. Owners borrowed money against their medallions and banked on them for retirement security. (In 2018, 131 medallions sold for $170,000 each in a bankruptcy auction.)

As Uber rolled out in city after city, a pattern emerged. The company would quickly win over riders with its slick service, and drivers with its pitch about earning extra money on their own schedules. It helped that Uber tended to pay drivers better at launch, and flooded riders with coupons that made its service extra affordable. But Uber reliably faced strong, vocal opposition from the local taxi industry and the regulators and politicians with close ties to it.

Uber usually didn’t even pretend to play by the rules. Following the playbook established by its early clash with San Francisco, the company ignored local regulations and decried politicians who tried to enforce them as out of touch. When challenged, Uber insisted it wasn’t a taxi company but rather a platform connecting people who needed rides with drivers who wanted to provide them, a talking point that would be adopted by many other “sharing” economy startups.

In August 2014, Uber hired former Obama campaign manager David Plouffe to lead its “campaign” against “Big Taxi.” In 2015, 22 states passed ride-hailing legislation that created rules favorable to Uber, a spectacular coup for the company and the ride-hailing model.

Global priorities

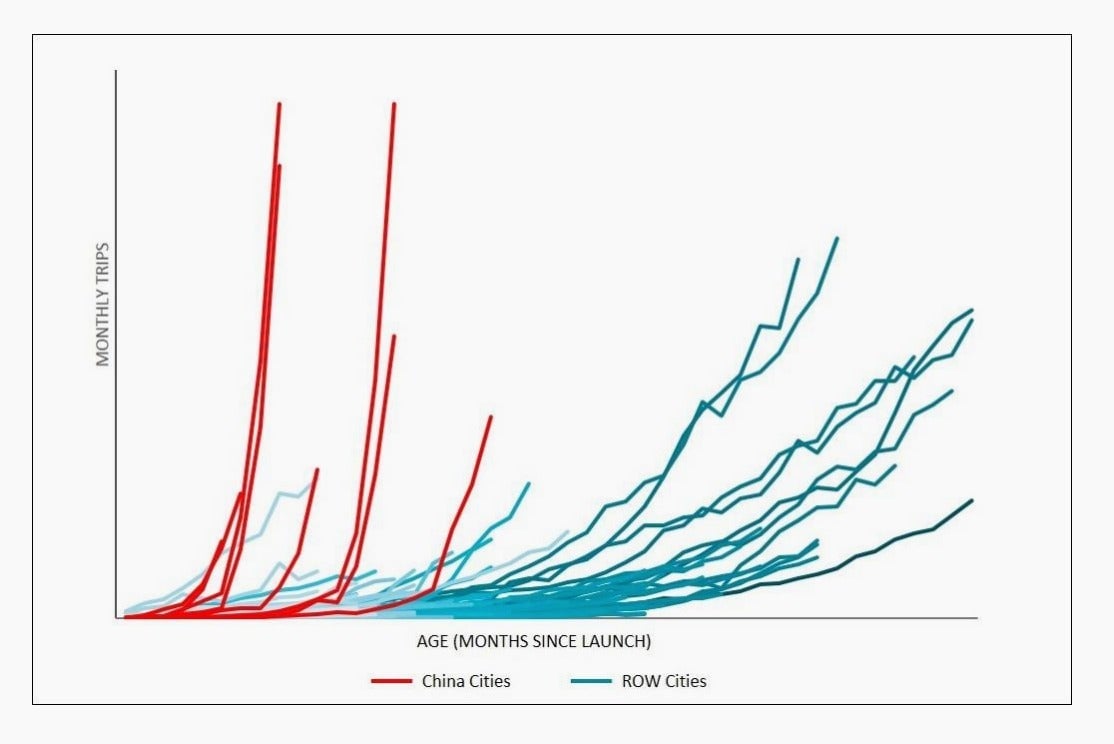

As Uber pulled ahead in the battle against the US taxi industry, Kalanick’s focus shifted to global markets—in particular, China. “Simply stated, China is the #1 priority for Uber’s global team,” he wrote in a letter to investors (pdf) in the summer of 2015.

China has long been a holy grail for global technology companies. China is huge, with more than a dozen cities of over 5 million people, meaning it offers unparalleled growth possibilities. It’s also notoriously difficult for foreign tech firms to do business because of the tight grasp the government keeps on the flow of information.

Uber was blessed by a strategic investment from Baidu, China’s leading search engine, but it still faced fierce local competition from taxi apps Didi Dache and Kuaidi Dache, which in February 2015 merged into the company that would become Didi Chuxing. Like Uber, Didi was well-funded, and spent heavily on discounts for riders and promotions for drivers to grow its market share. “You can go out, spend a bunch of money in a city and gain some market share, but that’s not real,” Uber’s then-head of Asia operations told the Financial Times in June 2016. “You’re just kind of buying all of it.” A few months earlier, Kalanick had revealed Uber was spending $1 billion a year to compete in China.

China wasn’t the only drain on Uber’s finances. The company faced stiff competition from companies that copied its model around the world. In July 2015, Uber committed $1 billion a year in spending to India, where it competed with local rival Ola. In Singapore, Indonesia, and other countries in Southeast Asia, Uber faced off against Grab and Go-Jek. In addition to being costly, these contests required Uber to cater to different needs from the US. It tested auto-rickshaws and cash payments in India, and motorbikes in Thailand.

Uber’s regional rivals in Asia were backed by powerful investors. Ola, Grab, and Didi collectively received hundreds of millions of dollars from Japanese tech conglomerate Softbank. Both Didi and Grab also counted Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba among their investors; Didi, Go-Jek, and Ola were backed by Tencent Holdings; even Apple put $1 billion behind Didi.

Uber won the US through wars of attrition. Uber had deeper pockets and it poured money into subsidies for drivers and consumers, then waited for the competition to bleed out. But in China and Southeast Asia, Uber met its match. In August 2016, Uber did a very un-Uber-like thing and surrendered. The company sold its China operations to Didi in exchange for $1 billion investment and a nearly 20% stake in the new combined entity.

Toe-stepping

Uber spent years selling drivers on the narrative that they could be their own boss and make good money by driving for Uber. It was a good story, especially as many Americans were still recovering from a recession that took their jobs and destroyed their savings. In 2014, Uber claimed half of its New York City drivers were making $90,000 or more. It convinced other drivers to sink money into subprime leasing arrangements to obtain cars approved for use on the Uber platform.

The problem was a lot of the story wasn’t true, and in mid-January 2017, Uber agreed to pay the US Federal Trade Commission $20 million for misleading drivers about their potential earnings, as well as misrepresenting the terms of its vehicle financing programs. Then, on Jan. 28, years of anger and resentment toward Uber broke open during a protest of the Trump administration’s immigration policies at John F. Kennedy Airport in New York.

The viral #DeleteUber campaign started from a tweet that claimed Uber had deliberately broken up an airport protest of Donald Trump’s first “Muslim ban.” That catalyzing tweet turned out to be misleading, but the emotions it unleashed were very real. More than 500,000 people were so ready to believe that Uber—a company that disdained the law, attacked politicians, mistreated drivers, and sported a rude and arrogant CEO—was evil, that they deleted the app from their phones.

#DeleteUber proved the start of a yearlong reckoning for Uber. In February, former Uber engineer Susan Fowler published a blog post detailing a year of harassment and systematic mistreatment at the company. Her account inspired others to share similar stories, leading Uber to initiate multiple internal investigations, dismiss several top executives, and fire dozens of other employees.

That same month, Kalanick was caught on tape berating his Uber driver after the driver complained about the company cutting prices. And Waymo, the driverless car company and subsidiary of Google parent Alphabet, sued Uber for allegedly stealing trade secrets. The lawsuit led Uber to fire Anthony Levandowski, then the head of its autonomous technologies research.

The first half of 2017 revealed the deeply toxic culture that Uber and Kalanick had cultivated as they built the ride-hail company. By mid-2017, Uber was no longer a small startup, but a company of roughly 15,000 employees spread across 450 cities, not to mention 2 million drivers. Corporate values that once seemed like typical tech-bro swagger—“always be hustlin'” and “meritocracy and toe-stepping”—took on darker overtones against alleged sexual harassment. Another corporate value, “principled confrontation,” seemed reckless in light of the Waymo lawsuit and a criminal probe into a software program designed to evade law enforcement.

On June 13, 2017, amid continued fallout, Kalanick announced a leave of absence as chief executive. A week later, Kalanick resigned after being pushed out by his own board in a messy power struggle. In August, as Uber searched for a new chief executive, major Uber investor Benchmark Capital sued Kalanick for fraud and breach of contract.

Moving forward

In late August 2017, roughly two months after Kalanick resigned, Uber named Dara Khosrowshahi as its next CEO. Previously the CEO of Expedia Group, Khosrowshahi was the dark horse in a bitter and protracted search process that included General Electric’s Jeff Immelt and Hewlett Packard Enterprise’s Meg Whitman. “I have to tell you I am scared,” Khosrowshahi wrote in a memo to Expedia employees after accepting the Uber job.

Uber took to Khosrowshahi quickly. The new chief executive had experience running a large global company, and displayed a calmer, more measured temperament than Kalanick ever did. Khosrowshahi smoothed over conflicts started under Kalanick’s leadership, such as London threatening to withhold Uber’s operating license (in June 2018, Uber received a provisional 15-month license, a major win for Khosrowshahi). He rebuilt the core management team, overhauled Uber’s corporate values, and ushered in important governance reforms, such as a “one share, one vote” policy that stripped Kalanick and other early Uber investors of outsized voting power. He landed a multibillion-dollar deal with Softbank.

In contrast to Kalanick, who famously said he would take Uber public “as late as humanly possible,” Khosrowshahi quickly committed to a 2019 Uber IPO. Many of the decisions Khosrowshahi has made in his nearly two years as CEO seem designed to get Uber in shape for an IPO—not surprising, as he has a huge payday riding on it.

In February 2018, Uber settled the trade secrets lawsuit with Waymo, less than a week after the case went to trial in US district court in San Francisco. Under the terms of the settlement, Waymo received 0.34% of Uber’s closely held stock, and Uber agreed not to incorporate Waymo’s confidential information into its hardware or software.

That March, Uber sold its Southeast Asia operations to Grab. The deal marked Uber’s third major concession to an international competitor, after it sold to Didi in China in 2016 and merged with Yandex.Taxi in Russia in July 2017. In a note announcing the sale, Khosrowshahi told staff Uber had spread itself thin, with “too many battles across too many fronts and with too many competitors.” For the first quarter of 2018, Uber booked its first-ever quarterly profit, thanks to the impact of paring down its international operations.

Khosrowshahi also pushed to make Uber more than a rides company. He put resources behind food delivery service Uber Eats and trucking platform Uber Freight, which launched in 2015 and 2017, respectively. Gross bookings for Eats grew from $824 million in the third quarter of 2017 to $2.6 billion in the fourth quarter of 2018. The new CEO also acquired e-bikes provider Jump Bikes and partnered with e-scooter provider Lime. Kalanick, to his credit, had the early vision of Uber as a logistics company. “If we can get you a car in five minutes, we can get you anything in five minutes,” he told Vanity Fair in 2014. Khosrowshahi helped to execute it.

Uber still has its share of scandals. Shortly into Khosrowshahi’s tenure, Uber disclosed a massive October 2016 data breach that it had previously paid hackers to cover up. In March 2018, a self-driving Uber SUV struck and killed a woman in Tempe, Arizona, in the first-known pedestrian death linked to driverless technology. The incident led Uber to suspend driverless tests on US public roads for the next nine months and overhaul its testing operations, laying off hundreds of people across several cities in the process.

The core business may also be in trouble. Aside from that one quarter in which it booked a profit after selling international operations, Uber remains chronically unprofitable. The company lost $890 million in the second quarter of 2018, $1.1 billion in the third, and $870 million in the fourth. (It booked a full-year profit in 2018 thanks to the first quarter.) In 2017, Uber lost over $4 billion, more than Amazon lost in its first 17 consecutive quarters as a public company, all of which were unprofitable. For the first quarter of 2019, Uber reported a net loss of around $1 billion on sales of roughly $3 billion.

Uber’s path to profitability is far from clear. Both ride-hailing and food delivery are highly competitive businesses. Uber admitted in the IPO filing it unveiled April 11 that it relies on “significant driver incentives and consumer discounts and promotions” and warned these discounts would likely continue. Uber also revealed that it charges lower fees to some of the largest restaurant chains on Eats, which can result in it losing money on those transactions. The danger of subsidizing a service for too long is that it can be difficult to quit those subsidies and hold onto your customers. Uber competitor Lyft, which went public on March 29, warned in its filing that it may never become profitable. The stock is down 20% from its IPO price.

Driverless cars, the technology on which Uber has staked its future, are also an expensive and far-from-sure bet. Kalanick, who described driverless cars as “basically existential” to Uber, believed they would make ride-hailing extremely profitable by eliminating its main cost, human drivers. Uber spent $457 million on research and development related to autonomous technologies in 2018, up from $384 million in 2017. It recently raised another $1 billion for that unit from investors including Softbank and Toyota. At Uber’s current pace of spending, that money could be gone in two years, though it seems unlikely the company will have a fleet of robotaxis to show for it by then.

Perhaps most worryingly for investors, Uber is slowing down. Uber generated $14.1 billion in gross bookings in the quarter ended Dec. 31, a figure that includes what customers spend on Uber rides, Uber Eats orders, and other Uber services. That translated to a growth rate of 30% year-over-year, the slowest growth the company reported all year. Uber grew revenue, or the share of money it keeps from those bookings, at 25% in the fourth quarter, also its slowest year-over-year growth rate in 2018. The share of revenue the company keeps on Eats orders, meanwhile, fell from 13.3% at the end of 2017 to 6.4% in the fourth quarter of 2018. Business at Uber continued to slow in the first quarter of 2019.

As it embarks on a traditional pre-IPO roadshow, Uber is hoping to convince prospective investors that it can be the Amazon of transportation. “We ignite opportunity by setting the world in motion,” the company says in large white font on a black background in the preface to its offering documents.

Whatever you believe about Uber, the slogan is true. Uber has completed more than 10 billion trips, expanded to over 700 cities on six continents, and amassed 91 million people who use its platform every month, a figure that exceeds the entire population of Germany. How the business fares in the public markets won’t change that Uber in 10 years pulled off a stunning feat, and changed the world in ways from which we’ll likely never look back.