In the composite image hanging in the high-ceilinged room, the face of the Ethiopian prime minister Abiy Ahmed is stenciled above a photo of pixelated subjects. They move with great haste, their jagged shadows heading in the same direction except for one person. And even though they look distracted, the people walk with assurance as if guided by the vision of their leader who, by virtue of his elevation, is able to see further than they can into the horizon.

The compositions, dubbed “Vantage Point,” are the works of Ethiopian artist and photographer Dawit Geressu who captures Addis Ababa’s humming streets. Yet Dawit adds a layer to his images by mixing digital photography with painting, pencil and stencil drawings and introducing influential figures or “icons” that have come to define these shared public spaces.

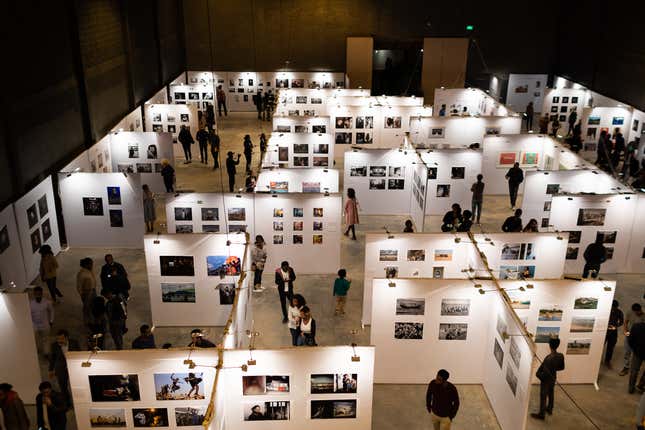

The images are part of the Ethiopian collection at the Addis Foto Festival, a biennial international photography event that aims to connect Africa and the world through visual representation. With 152 photographers from 61 nations exhibiting at the festival’s fifth staging, AFF has undoubtedly grown to become one of the leading artistic fetes in the continent.

This year 34 Ethiopian photographers are featured, many of whom are showcasing their work against a backdrop of increasing openness in the Horn of Africa nation. When the festival last happened in December 2016, the country was undergoing a winter of discontent that led to protests, a state of emergency, brutal killings, and arrests—eventually ending with the resignation of prime minister Hailemariam Desalegn in February this year.

Since then, premier Abiy has ushered in what some have called the “Ethiopian Spring,” overseeing seismic political and economic changes that have radically altered the trajectory of Africa’s second-most-populous nation.

Young Ethiopian photographers are seizing this opportunity in the hope of capturing the pervasive sense of hope, document the nation’s diversity, and reframe their story in a time of change. Images played a crucial role in shaping the pace of change in Ethiopia: whether it was a marathoner protesting government actions at the finish line in the 2016 Rio Olympics; protestors running from tear gas fired by police; or even the giddy excitement and hugs that defined the meeting of Ethiopian and Eritrean leaders after decades of hostility.

That visual culture has now extended into the prime minister’s palace too, with photographer Aron Simeneh hired to take photos of the premier’s travels and bilateral meetings—some of them so intimate they remind viewers of the disarmingly candid moments captured by Obama’s former photographer Pete Souza. Put together, these images confront Ethiopia’s past and connect it to its present, fusing themes of identity, memory, inclusion, and the place of power and politics.

Aida Muluneh, who founded the festival in 2010, says she was impressed with the “diversity and quality” of work that Ethiopian photographers submitted to the festival this year ranging from photojournalism to fine art. “To me, the photographers are trying to push the limit,” she said.

Looking at the past

One of the ways photographers are coming to terms with the current changes is to dig into the past for inspiration. Addis Aemero trained as an agricultural economist and for years didn’t follow in the footsteps of her family members many of whom were photographers. Struggling to make sense of the past and present, she traveled back home to the northern town of Weldiya, where her grandfather Sefiw Tebeje opened the first photo studio in 1976.

Her exhibition titled My grandfather, the photographer mix both her grandfather’s black and white photos and her own photos of him and his family. By developing his archive dating back to 40 years, Addis says she’s trying to find order in her life and craft her own story. The process of preserving old photographs has been growing in Ethiopia, with the recently-published book Vintage Addis Ababa gathering old photographs from private collections.

Photography also presents a way of upholding Ethiopian unity explains Abinet Teshome, a self-taught street photographer from Addis Ababa. With more than 100 million people and over 80 ethnic groups, the widening of the political space has presented challenges, some of the deadly, over which direction the country should take in the future.

Abinet has documented this transitional period, taking photos of the return of exiled opposition groups whose supporters carried once-banned controversial flags. To show the various factions’ commonalities, he shot photos of their allies under one tree as they all headed to the airport to welcome them on different days.

“We are one nation, and it is time to move past the ethnic divisions and into the future,” he said.

Yet to improve the significance of photography in Ethiopia would take a larger engagement from the government besides policy changes that would help improve the sector, argues Aida. One of the challenges that faced organizers included producing the photos in China because they couldn’t find suitable printers in Ethiopia.

Gaining the full relevance of an event like this is crucial for the government, Aida says, because it defines not only how the world looks at Ethiopia—and by extension Africa—but also how we relate to each other.

“We are promoting this country and in a contemporary way. We are promoting this country to show the renaissance of this place. And on top of that, we are having a global dialogue about this misrepresentation that exists when it comes to our continent.”

As the once-hostile Horn turns hopeful, Aida says she’s would like to extend the festival’s mission as a way to bring nations even closer. “I would like to take the Ethiopian collection to Asmara. That would be my dream.”

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox