Hi Quartz members,

“Let’s start with 7.5 billion—that’s the number of people on the planet,” Netflix chief product officer Greg Peters told an audience at Web Summit in 2018. “Of those folks, 1.5 billion speak English in some capacity; and of those, 360 million speak English as a native language or first language. Now, that is just 5% of the world’s population—and yet, a large majority of international content is produced in one place: in Hollywood, in the English language.”

Peters went on to outline Netflix’s fateful decision in 2014 to commission its first two international original series—Mexico’s Club de Cuervos and France’s Marseilles—and the company’s surprise in 2016, when Brazilian thriller 3% attracted global viewership.

Since then, Netflix’s global hits have included France’s Lupin, India’s Sacred Games, Spain’s Money Heist, Mexico’s Elite, and, of course, South Korea’s Squid Game—Netflix’s most successful show to date. Over 142 million accounts have viewed at least two minutes of Squid Game, which hit number one in 94 countries. Netflix estimates the show will be worth almost $900 million.

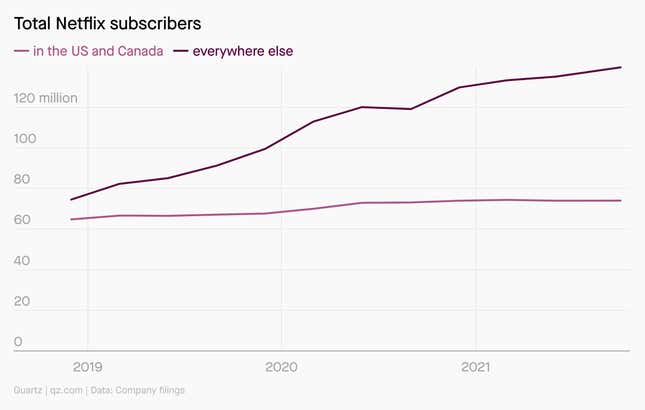

For younger TV fans raised on social media, the rise of the global mega-hit may feel quite natural. “[Gen Z] spends all day with people from all over the world who don’t necessarily reflect their national culture or language,” one veteran TV producer told Vox. But for Netflix, it’s by design, and necessity. The company’s subscriber growth in the US and Canada is flat—the region accounted for just 70,000 of the 4.4 million subscribers Netflix added last quarter—and it’s clear that future growth must come from elsewhere.

That’s why Netflix is spending $17 billion on content worldwide this year, and the company is likely relieved to have already laid that groundwork. In the US, Netflix is now turning its attention to public scrutiny and internal backlash over its handling of a controversial Dave Chapelle special.

How are you enjoying our member-exclusive emails? We’d like your feedback in this short survey.

By the digits

214 million: Netflix subscribers as of the third quarter

4.4 million: Total subscribers added by Netflix in the third quarter

1.6%: Portion of third-quarter new subscribers in the US and Canada (the Asia-Pacific region accounted for 50%)

35%: Overall share of Netflix subscribers in the US and Canada

$7.5 billion: Netflix’s third-quarter revenue, up 16% year over year

142 million: Netflix accounts that have viewed Squid Game since its Sept. 17 debut

83 million: Accounts that viewed previous record-holder Bridgerton in its first 28 days

6%: Share of TV viewing Netflix accounted for in September (tied with YouTube)

50%: Increase in viewing of foreign-language content on Netflix last year among US viewers

$500 million: How much Netflix is spending on Korean content this year

Growth mindset

Netflix’s next targets

The streaming giant doesn’t break out its content investment by country, but we do have some indicators of Netflix’s international interests:

- The golden age of French TV. Lupin was only ever designed to be successful in France, but 87% of its viewers came from outside the country. Now Netflix is working on 20 new French series and movies, and recently opened its first office in Paris. (It’s also working on more international heist dramas.)

- More storytelling out of Africa. With a population of 1.2 billion, Africa represents a huge opportunity. Netflix has invested in original programming like Queen Sono and King of Boys, dubbed American sitcoms in local languages, and launched lower-priced (or even free) plans in some African countries.

- New attempts at cracking India. India produces 2,000 films per year—more than the US—and might represent Netflix’s biggest single-market opportunity. Since launching in the country in 2016, Netflix has launched cheaper mobile-only plans, added Hindi to its interface, and upped investment in local productions. Crime series Sacred Games, which debuted in 2018, remains its most popular Indian show to date.

- Increased attention on anime. According to Netflix, more than 100 million households around the world watched at least one anime title in 2020, up 50% from the year before. Last year, Netflix dedicated an entire creative team to the genre.

Words of wisdom

“The reason Squid Game has such great meaning for us internally is that it’s perfect evidence that our international strategy has been right. We’ve always believed that the most locally authentic shows will travel best.” —Minyoung Kim, Netflix’s VP of content for Asia

What to watch next

These days, there’s more to choose from on Netflix than ever. So I asked Quartz’s global newsroom to give me their best non-English-language recommendations. Here’s a little of what’s in our queue:

🇳🇴 Home for Christmas, a Norwegian rom-com series that’s been compared to Bridget Jones.

🇫🇷 Call My Agent!, a French show about a talent firm with high-maintenance clients.

🇮🇹 Rose Island, a sweet, funny, and based-on-a-true-story Italian movie.

🇰🇷 Crash Landing on You, a Korean dramedy series with a memorable premise.

🇩🇪 The Billion-Dollar Code, a German miniseries about Google Earth’s predecessor.

Keep learning

- Netflix is feeding western audiences international entertainment (Quartz)

- The most popular Netflix movies and shows of all time (before Squid Game) (Quartz)

- The ascent of African entertainment (Quartz)

- Netflix’s third-quarter letter to shareholders (Netflix)

- Dave Chappelle’s special cost more than Squid Game (Bloomberg)

- The Chappelle controversy is a test of Netflix culture (Quartz at Work)

Have an binge-able end to your week,

—Kira Bindrim, executive editor (and subtitle addict)

With contributions from Adario Strange, Adam Epstein, and Leslie Nguyen-Okwu.

One 🦑 thing

“Everyone here has insurmountably large loans and stands at the precipice of life. Do you want to go home and live the rest of your life like garbage, being chased by creditors? Or do you want to grab this last opportunity, which we are presenting?” —a pink-clad Squid Game organizer

At the heart of Squid Game is a bitter theme: economic inequality in South Korea. The country’s household debt is increasing at the third-fastest speed among major economies, and about 8% of the population has borrowed money from three or more financial institutions simultaneously. In 2018, 43% of Korea’s elderly lived in poverty, three times the OECD average.

The country’s preoccupation with economic phenomena actually dates back even further, to the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997-1998. In what is often referred to as the International Monetary Fund Crisis, nearly 2 million Koreans lost their jobs under IMF-mandated restructuring plans.

Correction: last week’s email on Duolingo stated that advertising is its main source of revenue. In fact, subscription is the company’s primary moneymaker; advertising is second.