(H)ola Quartz members,

Ola wants to do it all: ferrying passengers in auto-rickshaws, building electric scooters, selling cars, delivering groceries, and even financial services.

Yet India’s largest homegrown ride-hailing firm has hit speed bumps ever since the covid-19 outbreak. Government-mandated lockdowns suspended cab services in April 2020. Once restrictions were lifted, offices remained shut and social gatherings muted. By March 2021, ride-hailing demand had recovered to just 70% of pre-covid levels.

The slowing mobility business prompted US-based investment firm Vanguard Group, which owns a small stake in Ola, to slash the company’s valuation to just under half its $6.5 valuation in 2019. Just as ride volumes were rebounding, a devastating second covid wave in April and May 2021 sent them plummeting yet again. If the omicron surge prompts cities to announce lockdowns, ride-hailing revenues will take yet another hit.

But Ola’s future is no longer just about giving rides.

The company’s latest ambition is to become India’s largest electric vehicle (EV) manufacturer. Back in May 2017, Ola started a small “electric mass transport project” within its ride-sharing app, building charging infrastructure and offering rides in 200 electric cars and auto-rickshaws. In March 2019, this initiative was spun off into its own company, Ola Electric Mobility; by July, it had become a billion-dollar business (now valued at $3 billion).

Ola hopes to translate that success into a slew of other ventures, from financial services to car sales to grocery delivery. What bodes well for these lofty ambitions is that Ola is now finally making money. In September, CEO Bhavish Aggarwal tweeted a chart showing gross merchandise value exceeded pre-Covid levels again (albeit with a dubious y-axis-less chart.) Ola also recorded its first ever operating profit in November—despite revenues dropping 65% from a year ago—thanks to aggressive cost-cutting and workforce reduction.

If all goes well, Ola will make its long-delayed stock market debut early this year.

By the digits

100 million: Customers Ola serves through taxis, rickshaws, and two-wheelers

$1 billion: Amount Ola plans to raise during its initial public offering

$8 billion: Ola’s target valuation for its IPO

150%: Growth in Ola’s auto-rickshaw business compared to pre-covid levels. The door-less three-wheeler, which is open on all sides, is perceived to be safer than cars.

3,000: Robots at work building and repairing Ola’s electric scooters

10,000: People Ola is looking to hire for its used-car business

3,079 and 2,661: Number of Ola drivers named Ramesh and Suresh, the two most common driver names in 2016

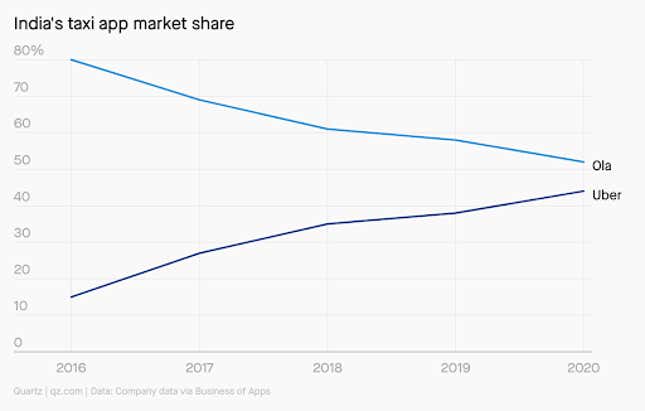

52%: Ola’s share in India’s taxi app market in November 2020

IPO on the way

India’s largest homegrown ride-hailing firm has been promising an IPO for years. It geared up for one in 2016. In July 2018, the firm said it would IPO in three to four years. In November 2019, before covid hit, it promised March 2021.

Most recent reports suggest Ola, founded in 2010, is now planning a $1 billion public debut in early 2022. The CEO also confirmed this timeline last month.

Ahead of the rumored IPO, the firm has rejigged its top management. Chief financial officer Swayam Saurabh and chief operating officer Gaurav Porwal are leaving the company, according to an internal memo seen by Reuters. After the high-profile exits, Ola also appointed several new leaders across Ola Financial Services, Ola Cars, and Ola Electric.

Before the IPO, though, there’s one promise Ola needs to deliver on: mass producing its electric scooters.

Scoot over

Ola’s scooter business is on a roll. Pre-bookings for the company’s electric scooters kicked off in July, and within 24 hours 100,000 Indians paid Rs499 ($7) to reserve their spot in the queue. On Aug. 15—India’s independence day—Ola teased the highly anticipated vehicles for the first time. When the e-scooters went on sale in September, it sold 80,000 in 12 hours.

But actual deliveries started in the slow lane. Initially planned for October, production was marred by delays; Ola started shipping its first scooters on Dec. 15. By the end of the year, the company says all purchased scooters were out for delivery. Aggarwal says that by early next year, the scooters will be exported to the US as well.

But Ola may still need to go back to the drawing board to better its product. Several scooter recipients have complained of damaged exteriors, delayed charger installations, and insurance policy discrepancies, among other things.

EV-erything Ola needs

- What’s working in favor of EV adoption in India? Petrol prices touching all-time highs: Covering 100 kilometers with the most fuel-efficient two-wheeler still costs 100 rupees ($1.30), while e-scooters can cover the same distance at one-sixth the price. More manufacturers, like Indian startups Hero MotoCorp, as well as international big names like Honda, are entering the Indian EV market and making it competitive.

- What’s working against EV adoption? Lack of public charging infrastructure, and also NIMBYism: Residential societies are even blocking private charging stations. One scooter owner charged it in his kitchen after his building refused to build chargers in the parking lot.

- What will make or break EV adoption? The price tag. Ola’s scooter sells for Rs100,000 ($1,336). The average annual income in India is $1,990. “Electric vehicles have a low operating cost and that’s something a lot of people know, but they also know that these vehicles have a very high upfront cost,” says Amit Bhatt, director of integrated urban transport at World Resources Institute India. “So bringing down the upfront cost using some innovative financial model can be the gamechanger for the industry.”

EVs are just the beginning

Ola’s diversification efforts go far beyond scooters. Keep your 👀 on:

🚗 Ola selling new and pre-owned cars. Instead of dealerships, people can buy via the company’s app, and Ola Cars sold 5,000 second-hand vehicles in its first month. Overall, Ola is looking to develop more mobility services for more aspects of Indians’ daily lives.

🛒 Ola taking aim at e-grocers. Companies like Big Basket and Nature’s Basket are pushing the envelope on “quick commerce” by piloting sub-15 minute delivery in Bengaluru. This is Ola’s second try at grocery delivery: It launched Ola Store in July 2015, but shuttered it within a year due to low margins and demand.

🥡 Ola doing more with food delivery. The company also offers takeout options from its own cloud kitchens.

💸 Ola offering more financial services. Six years ago, the company launched a wallet app to compete with payment outfits like Paytm.

A pretty picture

Over 10,000 women—a 100% female workforce—are employed at what will become Ola’s Future Factory in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu, in positions from tech roles to production assistants to supervisors. When fully operational, the factory will produce 1,000 scooters daily, or one every two seconds, for an annual total of 10 million.

Keep learning

- Ola, Uber, and the covid-19 slump (Quartz)

- Ola drivers on their triumphs and frustrations (Quartz)

- Ola’s rivals in the EV space are gearing up (Quartz)

- Inside India’s IPO frenzy (Quartz)

Thanks for reading! Don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or companies you want to know more about.

Best wishes for an fun-fueled end to your week,

—Ananya Bhattacharya, Quartz India reporter (just bought her first car)

One 🛵 thing

Pop quiz! Where was Ola headquartered when it launched in 2010?

A. Bengaluru

B. Mumbai

C. Hyderabad

D. Delhi

The answer is B. Ola’s first office was a 10-foot by 12-foot room in Mumbai, where Aggarwal would photograph drivers and take customer support calls while co-founder Ankit Bhati coded endlessly. Soon, the company shifted base to India’s Silicon Valley, Bengaluru, to be closer to investors and tech talent as well as save money on rent.