Hi Quartz members!

It’s never good news when the US president is expecting an imminent implosion from a major trade power. But Joe Biden’s recent reference to China as a “ticking time bomb” merely reflected the climate of intense anxiety that has built over the past few months. China’s economy is faltering to a degree that hasn’t been seen in its four recent decades of booming growth. Its trade and foreign investments are plunging, unemployment is surging, deflation is looming, demand is weakening, and its real estate crisis is growing. Tick, tick, tick.

As the pessimism reaches fever pitch, some close watchers say: We’ve seen this coming for years, not that this makes it any easier for the Chinese government to dig itself out of this economic morass. For one, there isn’t a single factor behind this period of economic instability—there are several, all pushing and pulling in different directions and influencing each other in different ways. Among them:

- China’s investment-driven growth model is running out of steam, so it is facing diminishing returns to its grand expenditure project of building more and more infrastructure.

- The Chinese economy is deeply unbalanced, with households’ share of GDP disproportionately low. As a result, China is hard-pressed to count on domestic consumption to drive growth.

- A mounting debt pile, with trillions of dollars owed by local governments and shadow banks, at best could be a drag on growth and at worst could trigger a series of destabilizing defaults.

- The heavy-handedness and unpredictability of Chinese president Xi Jinping’s authoritarian rule are suffocating market players and prolonging costly policy mistakes (think: a years-long, extreme zero-covid policy that defied both common sense and scientific reasoning).

In the background are more complicating factors still, chief among them China’s shrinking population, which augurs the dependence of ever-more retirees on an ever-smaller workforce, turning the country’s demographic dividend into debt. Then there are the geopolitical tensions with the West, which is girding against Beijing’s increasing aggression by reducing its dependence on China, and by levying severe tech trade restrictions upon it.

So much is going wrong, all at the same time, that there is no one, easy fix. Any serious attempt to reverse the slowdown will entail painful tradeoffs, both political and economic. And it will threaten the rule of Xi, who recently started his unprecedented third term as president, and whose vision for his nation’s economy is unraveling fast.

EXPOSED

China’s trade playbook generally has called for reducing its reliance on foreign countries, while increasing others’ dependence on itself. Now that strategy is running into stiff headwinds, as foreign investors and companies overseas scramble to reduce their China exposure.

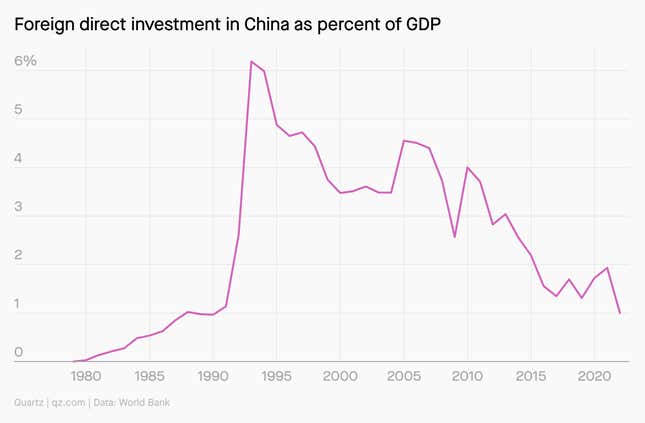

Foreign direct investment in China just fell to a record low, plunging nearly 90% on the year in the April-June quarter. Chinese authorities’ recent crackdown on foreign consulting firms—and their hints that the dragnet could expand further—certainly isn’t helping.

THE GREAT RECOIL

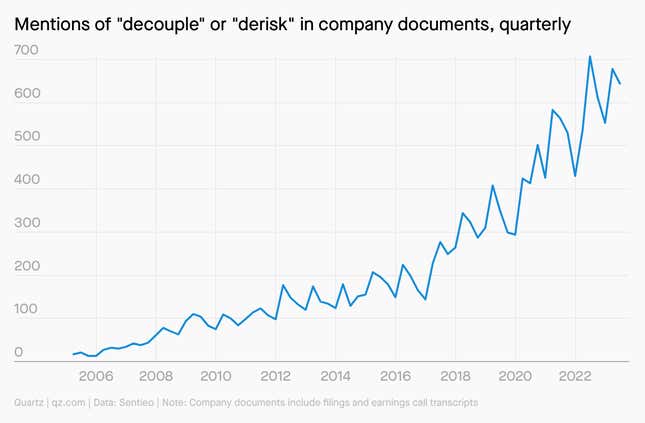

The West’s push to decouple and derisk from China threatens to derail the country’s economic ambitions. Beijing knows this: Just look at how eager Chinese state media was to portray Elon Musk as the government’s “ideal foreign investor” when the Tesla CEO visited China in May. But old habits are hard to break. In an editorial this week, the business news outlet Caixin argued that the Chinese government’s continued insularity is undermining foreign investment, a worrying trend that is “decidedly detrimental to…pursuing high-quality development.”

One encouraging thought for China is that the West’s derisking push is arguably a reaction to Beijing’s own actions—to its spy balloons, objectionable allies, industrial espionage, corporate antagonism, and more. That gives the Chinese government some degree of control over how the process of derisking ultimately plays out. “The driving element of multipolarity, decoupling, derisking, call it what you will, continues to be the [People’s Republic of China],” said John O’Connor, the CEO of JH Whitney Data Services, a geopolitical risk management consultancy. “The driving independent variable is: What does the PRC wish to accomplish?”

The derisking (and China’s consequent stumbles) are not without economic pain for the rest of the world. Big US companies like Caterpillar and DuPont, which count on China’s manufacturing industry as a huge market, will bear the brunt of poorer earnings, as the Wall Street Journal noted. Fewer Chinese travelers will head to destinations abroad that rely on tourism revenue. Western pension funds exposed to China will see their investments shrink.

China buys iron ore from India, crude oil from Malaysia, luxury products from France, soybeans from Brazil, and hundreds of products from other countries; a dire Chinese slowdown will hurt all these exporters. Further, if China loses its appetite for investing in green technology and renewable energy, the world’s already-tardy progress toward arresting climate change will slow down further still.

The economist Paul Krugman thinks a Chinese economic crisis will not trigger a 2008-style global meltdown. Perhaps he’s right. But over the next five years, the International Monetary Fund expected China to contribute nearly 23% of global growth—double the share of the US. It’s clear that if the Chinese economy suffers, the global economy as a whole does, too.

ONE 🇨🇳 THING

“Weaning China off steroidal industrial policies that feel good in the short run but are toxic in the long run is the key to sustained, high-quality growth and reconciliation of international disputes,” the economist Keyu Jin (and daughter of a former Chinese deputy finance minister) writes in The New China Playbook.

But no one is quite clear on what to replace those “steroidal” policies with.

One school of thought holds that Beijing must shift from an investment-driven economy to a consumption-driven one. That requires giving Chinese households more disposable income by transferring some portion of GDP away from local governments to consumers. Yet that would likely bring momentous changes in power structures. In this case, at least, to change the economics is to change the politics—a prospect that Beijing appears reluctant to experiment with.

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or topics you want to know more about.

Have an economically buoyant weekend,

—Mary Hui, reporter